- On average across 39 surveyed countries, health ranks second among the most important problems that Africans want their governments to address, trailing only unemployment as a priority for government action.

- Two-thirds (66%) of Africans say a family member went without needed health care during the previous year, including 25% who say this happened “many times” or “always.” In most surveyed countries, the experience of going without medical care has become more common over the past decade.

- Among the 58% of Africans who say they had contact with a public clinic or hospital during the previous year: More than half (55%) say it was easy to obtain the care they needed.

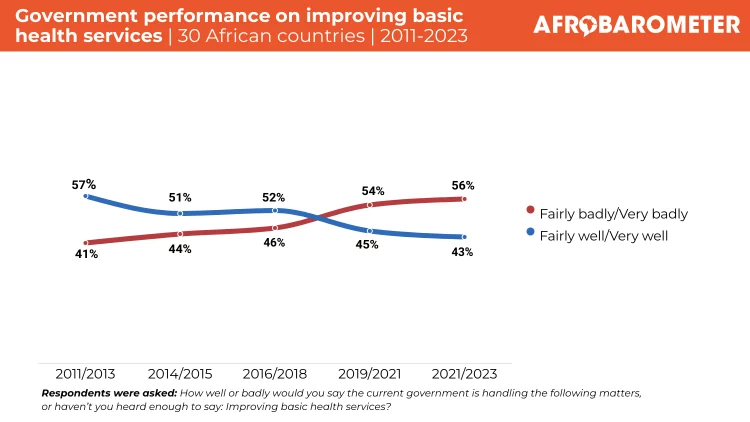

- While experiences vary widely by country, on average only 41% of Africans say their government is performing “fairly well” or “very well” on improving basic health services. Majorities in 27 of the 39 surveyed countries say their government is doing a poor job on health.

The theme of World Health Day 2024 (7 April) is “My health, my right” (World Health Organization, 2024). A key component of the message is to encourage governments to deliver on citizens’ right to health by making health services “available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality for everyone, everywhere.” How close are African governments to meeting this ambitious goal?

Since 1990, the burden of disease has decreased substantially in Africa (Roser, Ritchie, & Spooner, 2024; also see Figure A.1 in the Appendix). Between 2000 and 2019, Africa recorded the world’s greatest growth in healthy life expectancy, which rose from 46 to 56 years (Adepoju & Fletcher, 2022). Further, between 2015 and 2021, the under-5 mortality rate fell from 87 to 74 deaths per 1,000 live births across sub-Saharan Africa (United Nations, 2023). According to the World Health Organization, these gains were achieved through increased provision of essential health services and better access to care and disease prevention services (Adepoju & Fletcher, 2022).

Despite these important advances, however, many Africans still do not have access to high quality health care. Compared to other world regions, the gap is particularly acute when it comes to communicable, neonatal, maternal, and nutritional diseases (as opposed to non communicable diseases and injuries) (see Figure A.2 in the Appendix). While sub-Saharan Africa saw the world’s fastest growth between 2015 and 2022 in the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel, from 59% to 70%, the continent also recorded about 70% of the world’s maternal deaths (United Nations, 2023). At least part of the explanation is a lack of health workers; as of 2021, sub-Saharan Africa had an average of 2.3 medical doctors and 12.6 nursing/midwifery personnel per 10,000 people, compared to 39.4 and 89.5 in Europe (United Nations, 2023).

Focusing on health-system inputs, an analysis by the World Health Organization (2023) found that African countries made modest progress in running more efficient health-care systems between 2014 and 2019 but still lose one in five dollars due to technical inefficiencies.

As health-care systems recover from the additional operational and financial burdens placed on them during the COVID-19 pandemic, can Africans expect that their governments will provide accessible and high-quality health services for everyone, everywhere?

The latest Afrobarometer survey findings across 39 countries show that two-thirds of Africans report going without needed medical care at least once – and many of them doing so frequently – during the previous year. While a majority of citizens who sought care at a public health facility say they were treated with respect and found it easy to obtain the services they needed, a substantial minority – and in some countries a majority – say they had to pay bribes. Solid majorities complain of poor-quality services, including a lack of medicines or other supplies, absent medical staff, facilities in poor condition, and long wait times.

Overall, a growing majority of Africans say their government is failing to improve basic health services. Health ranks as one of the most important problems they want their government to address, second only to unemployment.

Related content