- Nearly two-thirds (64%) of Cameroonians say they felt unsafe while walking in their neighbourhood at least once during the previous year, while 43% report fearing crime in their home. Poor citizens are far more likely to be affected by such insecurity than their better-off counterparts.

- About one in seven citizens (14%) say they requested police assistance during the previous year, while almost five times as many (65%) encountered the police in other situations, such as at checkpoints, during identity checks or traffic stops, or during an investigation. o Among citizens who asked for help from the police, 52% say it was difficult to get the assistance they needed, and 63% say they had to pay a bribe. o Among those who encountered the police in other situations, 52% say they had to pay a bribe to avoid problems.

- More than six in 10 citizens (62%) think “most” or “all” police are corrupt, the second worst rating among 11 institutions the survey asked about.

- Fewer than half (44%) of Cameroonians say they trust the police “somewhat” (25%) or “a lot” (19%).

- Substantial shares of the population say the police “often” or “always” use excessive force with suspected criminals (55%) and with protesters (47%), stop drivers without good reason (46%), and engage in criminal activities (34%).

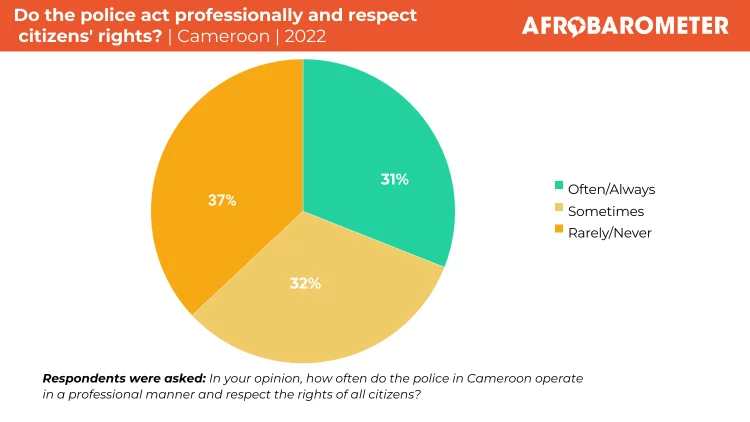

- Fewer than one-third (31%) of Cameroonians say the police “often” or “always” operate in a professional manner and respect all citizens’ rights. o But most (84%) consider it likely that the police will take reports of gender-based violence seriously.

- Four in 10 citizens (40%) say the government is doing a “fairly good” or “very good” job of reducing crime, while 59% are critical of the government’s performance on this issue.

The police are supposed to keep Cameroonians safe, but headlines often tell a different story, highlighting police abuses and tensions with the citizens they are paid to serve. In one extreme case in 2021, a police officer in Buea was lynched after he fatally shot a 5-year-old girl when the car she was in failed to stop at a checkpoint (Al Jazeera, 2021). Just weeks later, almost identical circumstances in Bamenda led to the death of a 7-year-old girl, followed by demonstrations against police brutality in which at least one protester was killed (Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa, 2021).

More often, critics complain of police harassment and arbitrary arrests – sometimes targeting journalists and political activists – as well as prolonged detention, beatings, and everyday corruption at checkpoints (U.S. Department of State, 2021, 2022; Guardian Post, 2023; Forkum, 2016; Human Rights Watch, 2022).

To address long-standing abuses, the government created a special police oversight division (known as “the police of the police”) in 2005, but local and international rights groups have criticised it as lacking independence and objectivity (United Nations Committee Against Torture, 2010; Forkum, 2016).

Illustrating strained police-community relations, the police in 2021 complained about a growing number of citizens who refuse police orders and mock or assault the officers – incidents that are often shared in videos on social media (Kindzeka, 2021).

This dispatch reports on a special survey module included in the Afrobarometer Round 9 questionnaire to explore Cameroonians’ experiences and assessments of police professionalism.

Survey findings show that fewer than one-third of Cameroonians say the police generally operate in a professional manner and respect all citizens’ rights. Majorities say at least some officers use excessive force with protesters and suspected criminals, stop drivers without good reason, and engage in criminal activities.

Vast majorities of citizens think that “most” or “all” police officers are corrupt, and among those who encountered the police during the previous year, more than half say they had to pay a bribe to get help or avoid problems.

Overall, a majority of Cameroonians say the government is doing a poor job of reducing crime.

Related content