- Responsibility for holding MPs accountable: A majority (56%) of Ugandans say voters are responsible for making sure that MPs do their jobs. This proportion has increased by 11 percentage points since 2015.

- Knowing your MP: In 2008, more than seven out of 10 Ugandans (73%) could name their elected representative – far above the 45% average across Afrobarometer’s 20- country sample.

- Constituency service: About one in seven Ugandans (15%) say they contacted an MP at least once in 2021. Only 15% of citizens say MPs try their best to listen to ordinary citizens.

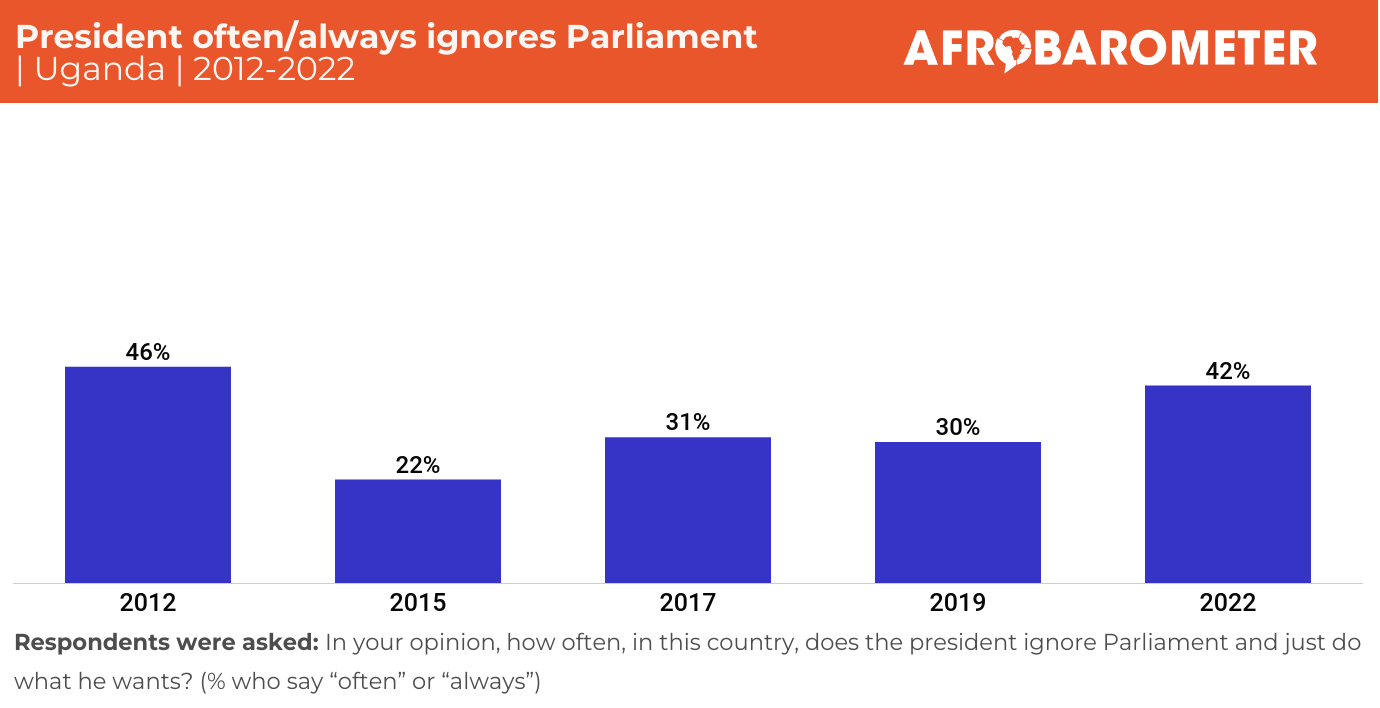

- Oversight: Three out of four Ugandans (75%) say the president should be accountable to Parliament. But since 2015, the share of citizens who say the president “often” or “always” ignores Parliament has increased from 22% to 42%.

- Corruption among MPs: In 2005, 25% of Ugandans said “most” or “all” MPs were corrupt. This has steadily increased to 44% in 2022.

- Determinants of MP performance ratings: Satisfaction with MP performance varies by region and by whether citizens think MPs listen to them and are free of corruption, rather than by MPs’ ability to conduct oversight of the executive.

Uganda’s legislature is made up of 556 members of Parliament (MPs) who are meant to represent and serve their constituents and oversee the government’s actions. Since President Yoweri Museveni and the National Resistance Movement (NRM) party came to power in 1986 and appointed all members of Parliament, the country’s legislature has changed in several important ways (Kasfir & Twebaze, 2009). First, today all MPs are either directly elected via a first-past-the-post system or indirectly elected via special electoral colleges.

Second, the number of parliamentarians has almost doubled over 25 years, from 295 in the 6th Parliament (1996-2001) to 556 in the current 11th Parliament (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 1996; Parliament of Uganda, 2022).1 This drastic increase can be attributed to the continued creation of new constituencies and the allocation of parliamentary seats for special-interest groups. Proponents of this development say it reflects citizens’ demands, but critics describe it as part of a political strategy to protect and grow the ruling party’s seat share in Parliament by increasing the number of constituencies in NRM strongholds (Nakatudde, 2020; Tumushabe & Gariyo, 2009). This debate has now entered a new phase with the recent ruling by the country’s Constitutional Court that Parliament and the Electoral Commission violated articles 51 and 63 of the Constitution by creating new constituencies that do not meet the population quota, based on data from the 2002 and 2014 census counts. The upshot of this ruling are proposals to downsize Uganda’s Parliament and redraw constituency boundaries (Barigaba, 2022).

Third, the operating costs of the growing Parliament (MP and staff salaries, allowances, etc.) have increased drastically over the past two decades. Today Ugandan MPs’ salaries (35 million Uganda shillings, or about USD 9,700, per month) surpass those of most MPs elsewhere in Africa and in the European Union (BusinessTech, 2017; Olukya, 2021; Tumushabe & Gariyo, 2009). The cost of running Uganda’s 11th Parliament was expected to increase by more than 50 billion Ugandan shillings (USD 14.1 million), a substantial increase compared to the previous Parliament (Mufumba, 2021).

Fourth, the share of MPs who return to Parliament after their first term in office continues to decrease. While about 50% of MPs did not return for a second term in the 6th (1996-2001) and 7th (2001-2006) Parliaments, this rate has increased to 53% (2006-2011), 55% (2011-2016), and 58% (2016-2021) in subsequent Parliaments. Most recently, of the 457 MPs in the 10th Parliament, 319 were not voted back to the 11th Parliament (2021-2026), while 31 did not contest or chose to run for other offices, and only 107 MPs returned (Kasfir & Twebaze, 2009; Forum for Women in Democracy, 2016; Independent, 2021).

How do these changes affect 1) how citizens relate to their elected representatives and 2) how MPs address the needs of ordinary citizens? More broadly, are citizens being served by their MPs? To answer these questions, this policy paper begins by clarifying the foundations of the citizen-MP relationship and outlining the four key roles that MPs are generally expected to fulfil. The subsequent sections assess their performance in these roles against citizen expectations and other indicators.

We find that Ugandans are becoming increasingly aware of their role in holding their MPs accountable. Most citizens are dissatisfied with how their MPs are doing their jobs, perceive them as corrupt, and say MPs don’t listen to constituents’ concerns. Residents of the Central region and Kampala are particularly critical of their MPs’ performance, probably due at least in part to high constituent-to-MP ratios in those areas.

Citizens’ assessments of MP performance are associated with MPs’ perceived responsiveness and corruption as well as whether citizens have had contact with their MPs. In contrast, citizens’ demographic characteristics and views about democracy do not seem to drive their views of their elected representatives.

There are two clear policy implications of these findings. First, at the institutional level, it is important to even out the citizen-to-MP ratios across the country. This is in line with the recent constitutional court ruling to base the creation of constituencies on census data. The second policy implication of our findings is that MPs have it in their own hands to change how citizens view their performance by improving on how they engage with them.

Related content