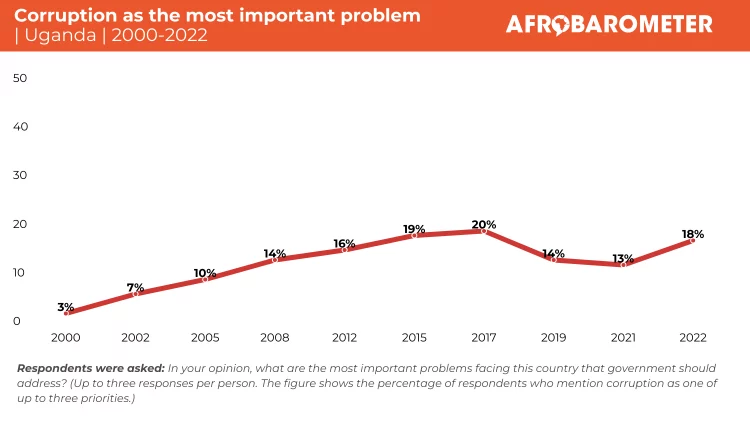

- Six in 10 Ugandans (62%) say corruption in the country increased “somewhat” or “a lot” during the year preceding the survey, a slight improvement compared to citizens’ perceptions in 2015 and 2017 (69%).

- Almost three-fourths (73%) of Ugandans say the government is performing poorly in its fight against corruption. Dissatisfaction with government efforts to reduce corruption has grown significantly since 2005 (52%).

- More than three-quarters (77%) of Ugandans believe that citizens who report corruption to the authorities risk retaliation or other negative consequences.

- More than two-thirds (68%) of citizens say “most” or “all” police officials are corrupt. Almost half see widespread corruption among civil servants (48%) and tax officials (45%).

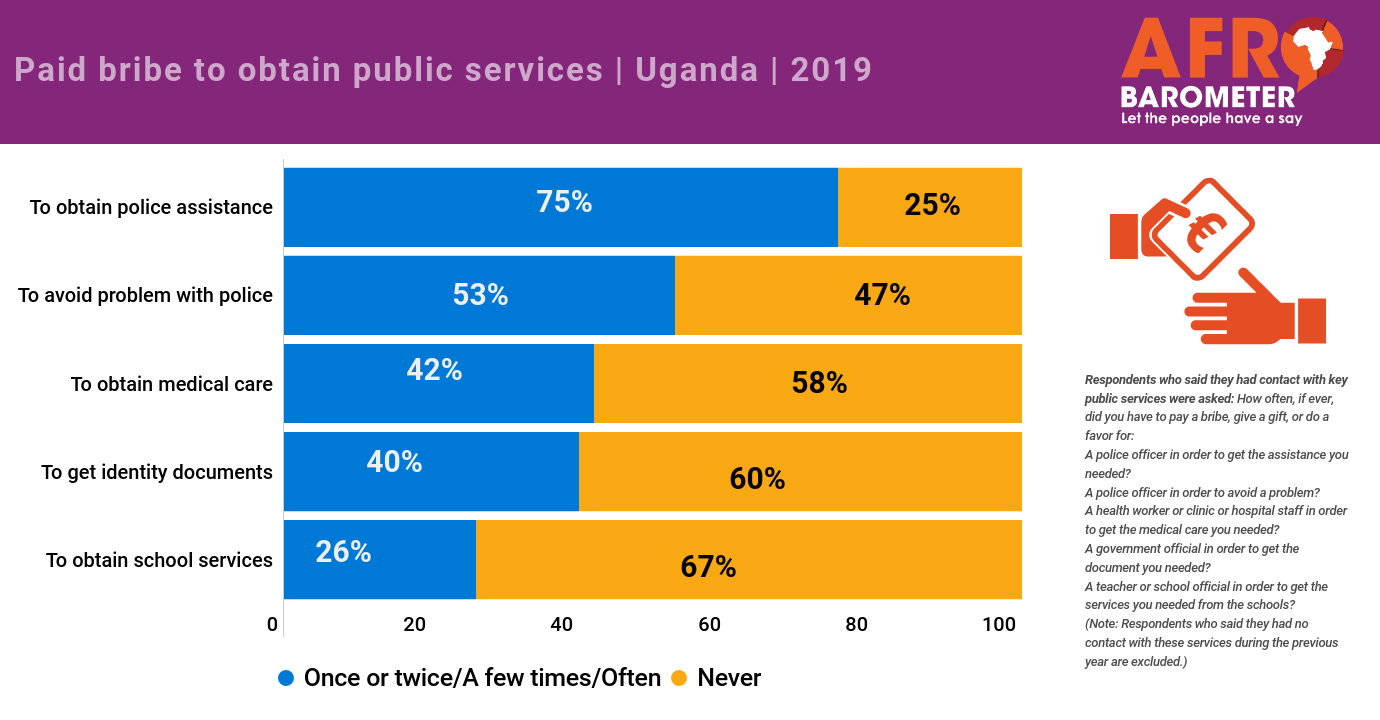

- Among Ugandans who had contact with key public services during the previous year, three-quarters (75%) say they had to pay bribes to obtain police assistance. Four in 10 say they had to pay bribes to obtain medical care (42%) or to get a government document (40%).

Corruption hinders economic, political, and social development, especially in less-developed countries, and has a disproportionate impact on the poor and most vulnerable, increasing costs and reducing access to services, including health, education, and justice. Corruption worsens poverty and aggravates inequality as resources meant for the poor and the underprivileged are diverted to line the pockets of the corrupt (Addah, Jaitner, Koroma, Miamen, & Nombora, 2012). In his State of the Nation address in 2019, President Yoweri Museveni called corruption “Public Enemy No. 1,” the remaining obstacle to Uganda’s development (State House of Uganda, 2019; Daily Monitor, 2019a).

To tackle endemic corruption, the government has passed a variety of laws, including the Inspectorate of Government Act (2002), the Leadership Code Act (2002), the Public Finance and Accountability Act (2003), the Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Act (2003), the Access to Information Act (2005), the Audit Act (2008), the Anti-Corruption Act (2009), the Whistle Blowers Protection Act (2010), and the Public Finance Management Act (2013) (Gumisiriza & Mukobi, 2019).

Government agencies have been established to deal with reported corruption, including the Inspectorate of Government (IG), the Office of the Auditor General (OAG), the Directorate for Public Prosecution (DPP), the Directorate for Ethics and Integrity (DEI), the Anti-Corruption Court, and the State House Anti-Corruption Unit.

The president has demonstrated some level of commitment in the fight against corruption. In 2006, he announced a policy of zero tolerance for corruption. In 2016, he vowed to renew the fight against corruption when he took the oath for his fifth term in office. In 2019, he led an anti-corruption walk in Kampala (Xinhuanet, 2019).

But critics dismiss the walk as political theater (VOA, 2019) and say corruption remains widespread in the government. In their view, while agencies have been successful in prosecuting graft involving lower-level officials or private citizens and small amounts of money, they have largely “let the big fish swim” (Human Rights Watch, 2013; Transparency International, 2018).

Reports by the Auditor General’s office state that corruption is getting worse, with more public funds being misappropriated in increasingly sophisticated ways (Inspectorate of Government, 2014). In its Corruption Perceptions Index, Transparency International (2019) ranks Uganda among the most corrupt countries in the world (137th out of 180). The Ibrahim Index of African Governance rates Uganda worse than average among African countries, better than regional peers Burundi and South Sudan but worse than Tanzania, Kenya, and Rwanda (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2018).

Afrobarometer survey findings show that a majority of Ugandans think that corruption is getting worse in their country and that their government is doing a bad job of fighting it. Most say ordinary people risk retaliation if they report corruption to the authorities.

Among key public institutions, the Uganda police are most widely seen as corrupt, followed by civil servants and tax officials. Paying bribes is a common part of daily life in Uganda: More than half of respondents who accessed police services say they had to pay a bribe.

Related content