- On average across 39 countries, Afrobarometer teams found police stations, police officers, and/or police vehicles in 46% of surveyed locations – 64% in cities and 29% in rural areas.

- Among respondents who sought police assistance during the previous year, 54% say it was easy to get the help they needed.

- Only one-third (32%) of citizens say their police “often” or “always” operate in a professional manner and respect the rights of all citizens, ranging from just 13% in Nigeria to 58% in Burkina Faso.

- Almost half (46%) of citizens say “most” or “all” police officials are corrupt, the worst rating among 11 public institutions and leaders the survey asked about.

- Among respondents who sought police assistance, 36% say they had to pay a bribe to get the help they needed. Among those who encountered the police in other situations, 37% report having to pay a bribe to avoid problems, ranging from 1% in Cabo Verde to 70% in Liberia.

- Across 39 countries, three in 10 citizens (29%) say their police “often” or “always” engage in criminal activities, in addition to 27% who say they “sometimes” do.

- On average, about four in 10 Africans say their police “often” or “always” use excessive force in managing protests (38%) and dealing with suspected criminals (42%).

- Police presence and contact are not significantly correlated with perceptions of police professionalism, police corrupt behaviour, or police brutality. But high levels of police professionalism are correlated with perceptions of less police corruption and police brutality.

- On average across 39 countries, 48% say they never felt unsafe walking in their neighbourhood during the previous year, and 59% say they never feared crime in their home. Lower perceptions of corrupt activity by the police are significantly associated with more widespread feelings of being safe in one’s surroundings.

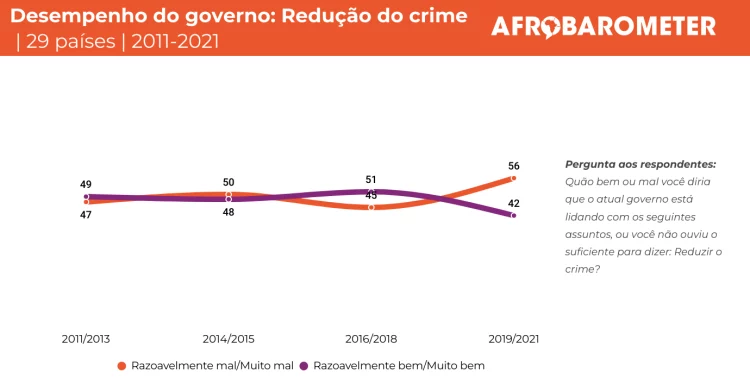

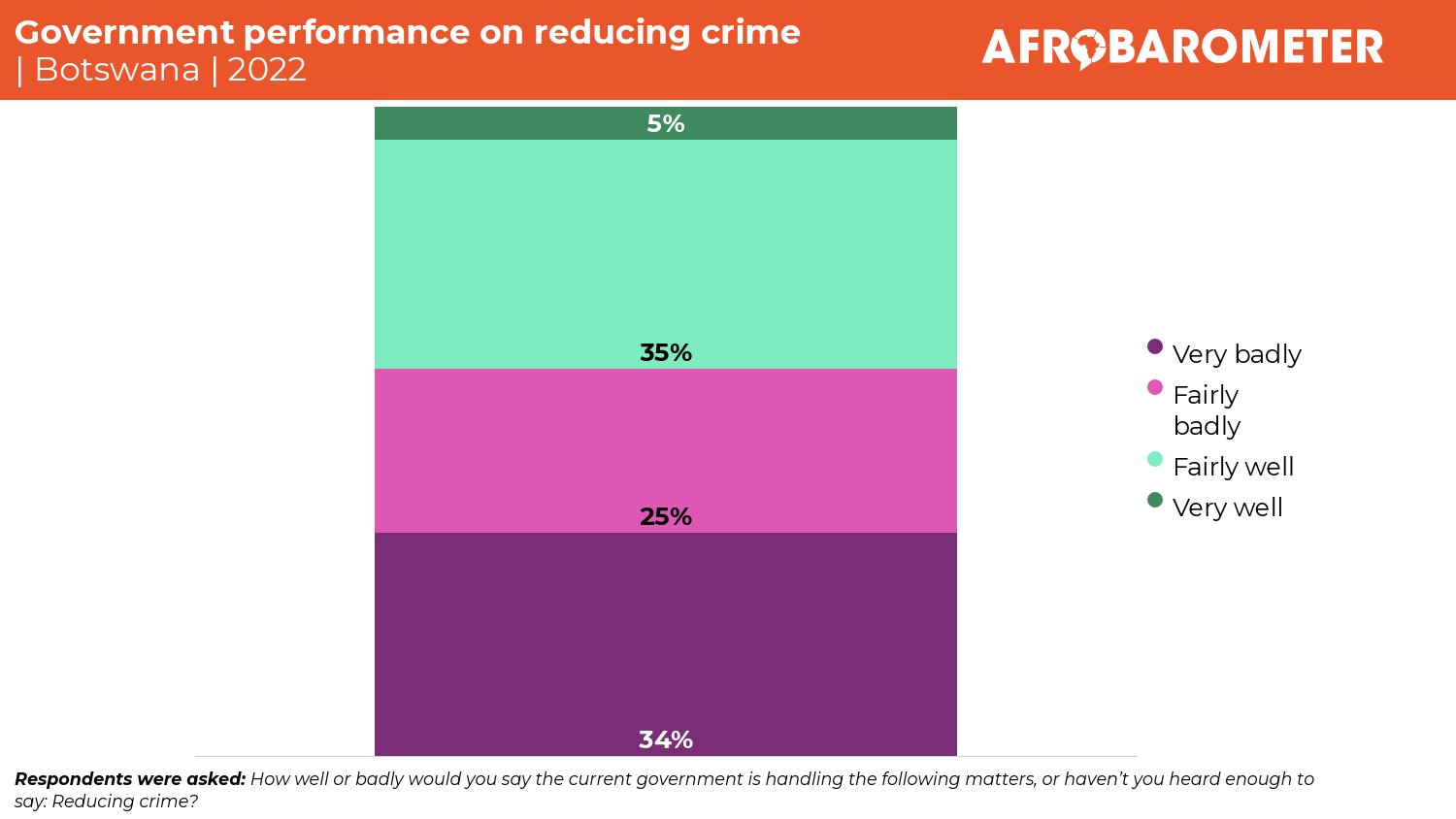

- Fewer than four in 10 citizens (37%) say their government is doing “fairly well” or “very well” at reducing crime, ranging from just 10% in Sudan to 77% in Benin. Countries with higher scores on police professionalism tend to record better government performance evaluations on crime.

- Fewer than half (46%) of citizens say they trust the police “somewhat” or “a lot.” Perceived police professionalism is strongly associated with citizens’ trust in the police.

In late 2020, Nigerians gripped the world with massive protests against police brutality and impunity, focusing on the country’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) (Al Jazeera, 2020; George, 2020). Three years after pictures of the #EndSARS demonstrations went viral and the SARS unit was disbanded, at least 15 protesters remain in arbitrary detention, and reports of police abuses continue unabated (Agboga, 2021; Amnesty International, 2021, 2023a; Uwazuruike, 2021).

Elsewhere in Africa, and in other parts of the world, the media frequently report on unprofessional behaviour, selective enforcement of the law, unlawful arrests, corruption, use of excessive force, and other human-rights abuses by the police (New York Times, 2022). These violations are not limited to suspected criminals and public protests against the police, as in the case of #EndSARS, but also occur during pivotal moments of democratic accountability (e.g. elections), health emergencies (e.g. COVID-19), and routine citizen police encounters (e.g. traffic stops).

For example, recent elections in Zimbabwe (2023), Uganda (2021), and Tanzania (2020) were marred by police repression and brutality targeting opposition politicians and their supporters (Reuters, 2023; Human Rights Watch, 2023a; Kakumba, 2022; Salih & Burke, 2020). During the 2021 election campaign in Uganda, security forces killed at least 54 people (Amnesty International, 2020).

In October 2022, Chadian security officers were accused of killing 128 people and injuring many more during demonstrations calling for a quicker transition to democratic rule (Human Rights Watch, 2023b). Two months earlier, more than 20 people were killed during protests against the soaring cost of living in Sierra Leone (Amnesty International, 2023b). Police brutality and extrajudicial killings have been reported in other African countries as well, from Guinea to Kenya and Senegal to Sudan, including during enforcement of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in 2021 (Amnesty International, 2023c; Diphoorn, 2019; Logan, Sanny, & Katenda, 2022).

More frequently, citizens confront demands for bribes from the police, who are regularly cited as one of the most corrupt government institutions (Kakumba & Krönke, 2023; Keulder, 2021; Wambua, 2015a, 2015b).

Against this background, Afrobarometer surveys offer new evidence of how Africans view the professionalism of their police forces. Data from 39 African countries, collected between late 2021 and mid-2023, highlight issues of misconduct, criminal behaviour, brutality, and corruption.

While experiences and assessments vary widely by country, only one-third of Africans say their police generally operate in a professional manner and respect all citizens’ rights. Many say law enforcement officers routinely use excessive force against protesters and suspected criminals.

Among citizens who had encounters with the police during the past year, a majority found it easy to obtain assistance, but many report having to pay a bribe to get help or avoid a problem. The police remain widely perceived as corrupt.

Our analysis also reveals that negative perceptions of police professionalism and corruption go hand in hand with low public trust in the police, poor marks on government performance, and citizens’ sense of insecurity. Despite fairly high police visibility in many countries, our results suggest that this does not improve citizens’ attitudes toward the police.

Related content