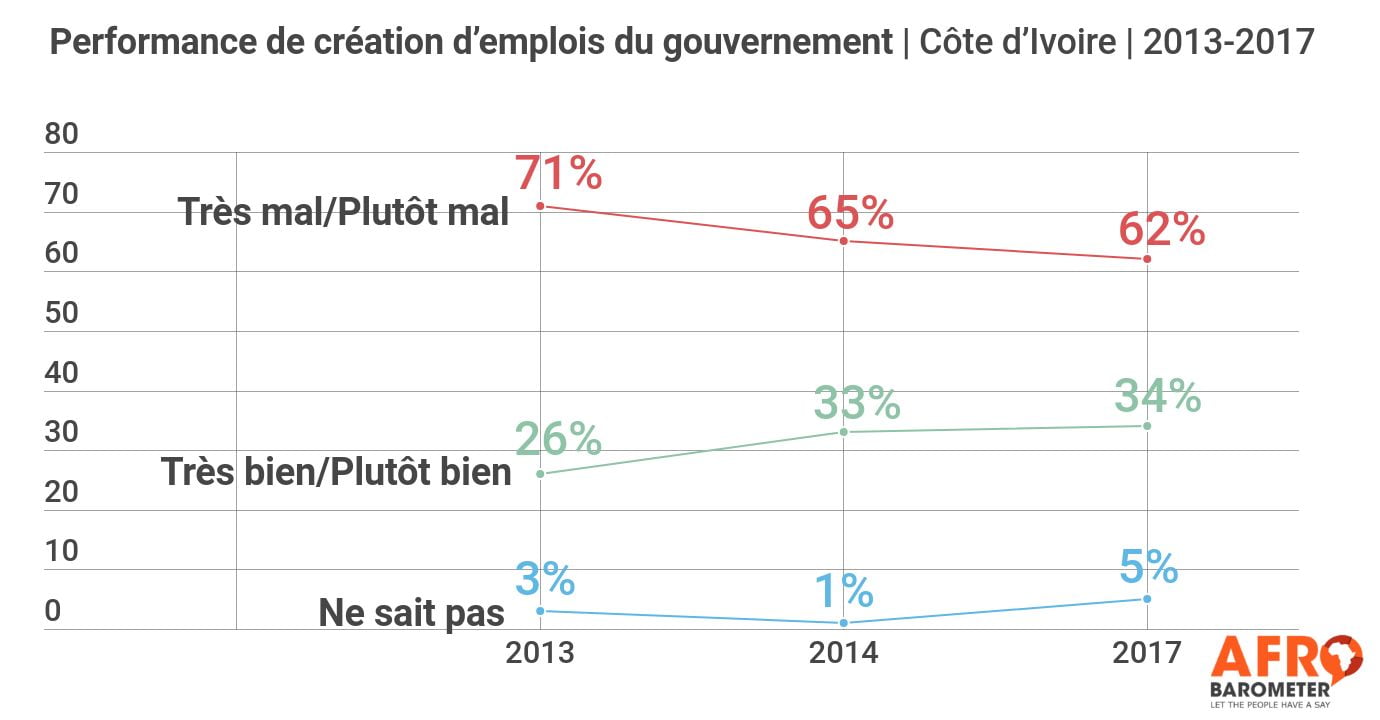

Since the end of its civil war in 2011 and the installation of President Alassane Dramane Ouattara, Côte d’Ivoire has seen one of the highest rates of economic growth in Africa, sometimes referred to as a new “Ivoirian miracle” (Dionne & Bamba, 2017). As the economy has grown and the state has rebuilt capacity, tax revenues have increased steadily, growing by 37% between 2013 and 2017.

In many African states, «import and export taxes constitute the backbone of tax regimes. Revenues are supplemented by indirect taxes, in the form of excise and sales taxes» (D’Arcy, 2011). In the case of Côte d’Ivoire, the government relies heavily on taxes on the export of cocoa and other agricultural products, in addition to taxes on industrial and commercial profits, income, telecommunications, petroleum products, imports, as well as a value-added tax (Ministère du Budget et du Portefeuille de l’Etat, 2020).

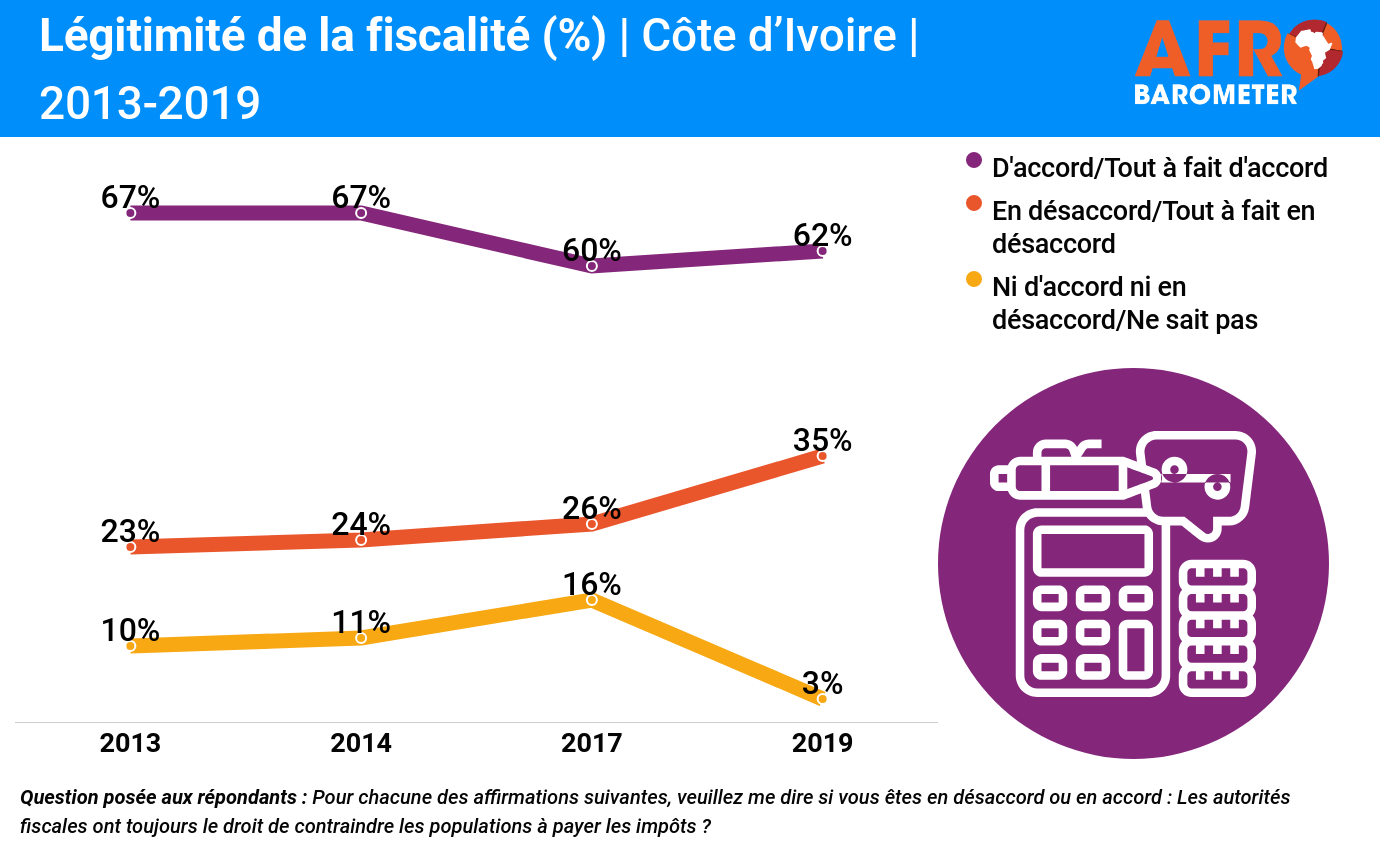

Even in states with high levels of coercive capacity, citizens’ willingness to pay taxes is a significant determinant of revenues collected. This willingness becomes even more important in contexts of relatively low state capacity, such as has existed in post-conflict Côte d’Ivoire.

In fact, a substantial – and growing – proportion of Ivoirians question the state’s right to collect taxes, a fact that could present a significant challenge to the government’s ability to collect revenues in order to rebuild essential state services and avoid excessive debt.

This paper focuses on a particular form of tax non-compliance: tax disobedience, or individuals’ refusal to pay taxes and fees as a form of protest. Specifically, it examines several individual-level factors that might be associated with tax disobedience, including lack of a cash income, assessments of public services and elected representatives, accessibility of information, and effective connections with the Ivoirian nation.

Our analyses of data from the Afrobarometer Round 7 survey (2017) suggest that some of the conventional wisdom on tax compliance is not supported in the case of tax disobedience in Côte d’Ivoire. While we find, as expected, that individuals who think state performance is improving in delivering key services are less likely to express a willingness to engage in tax disobedience, we find no such link with lived poverty; poorer Ivoirians are no more or less likely than their wealthier counterparts to endorse tax disobedience. Surprisingly, assessments of elected representatives and of corruption in the tax system are not significantly associated with tax disobedience, either.

Perceived access to government information and identification with the Ivoirian nation do show associations with tax disobedience, but these links run counter to our expectations: Citizens who think they could access information held by public bodies are significantly more likely to say they engaged or would engage in tax disobedience, as are people who identify more closely with the nation than with their ethnic group.

These analyses suggest the need for more research on a crucial question facing African states: Who pays taxes, and who doesn’t?