- Three-fourths (75%) of Africans support fair, open, and honest elections as the best way to choose their leaders, including 50% who “strongly agree” with this view (Figure 1). o More than six in 10 citizens support elections in all surveyed countries except Lesotho, where a majority (54%) favour other methods for choosing leaders. Support for elections ranges up to about nine out of 10 citizens in Liberia (92%) and Sierra Leone (89%) (Figure 2). o Support for electing leaders increases with age, ranging from 73% among 18- to 35-year-olds to 78% among those over age 55. It is notably stronger in East Africa (83%) and West Africa (79%) than in other regions (69%-71%) (Figure 3).

- However, while support for choosing leaders via elections remains robust, it has declined significantly over the past decade (Figure 4). On average across 29 countries where this question was asked in both 2011/2013 and 2021/2023, this support has dropped by 8 percentage points, including massive declines in Tunisia (-24 percentage points), Burkina Faso (-19 points), and Lesotho (-19 points). Sierra Leone is the only surveyed country that records significantly increased support for elections (+13 points).

- Nearly two-thirds (64%) of Africans support multiparty competition to ensure that voters have real choices in who governs them, while 34% think political parties foster division and confusion and their country doesn’t need many of them (Figure 5). o Demand for a multiparty system exceeds three-fourths of adults in nine countries, led by Congo-Brazzaville (81%), Botswana (80%), and Seychelles (80%) (Figure 6). But fewer than half of citizens want party competition in Tunisia (32%), Lesotho (34%), Sudan (38%), Burkina Faso (39%), Mali (40%), São Tomé and Príncipe (41%), and Guinea (43%) – in many cases countries that have experienced crises, attempted or successful coups d’état, or even civil war. o On average across 30 countries surveyed consistently since 2011/2013, support for multiparty competition has been stable around about two-thirds (62%-64%) of the population. But country-level changes have been striking, including double-digit increases in support in Eswatini (+31 percentage points), Botswana (+18), Kenya (+17), and Senegal (+17). In contrast, support for party competition has declined sharply in Lesotho (-36 points), Niger (-20), Mali (-18), Burkina Faso (-17), and Guinea (-14) (Figure 7). o The desire for a multiparty system is somewhat weaker among older citizens (-7 percentage points), much weaker among less educated citizens (-16 points), and particularly weak in North Africa (44%, vs. 79% in Central Africa) (Figure 8).

- Almost three-fourths (73%) of citizens say that after losing an election, the opposition should cooperate with the government to help develop the country, rather than monitor and criticise the government to hold it accountable. This is the majority view in all surveyed countries, ranging from 55% in Mauritania to 84% in Cabo Verde (Figure 9).

- Almost matching support for elections, self-reported voter turnout in their country’s most recent national election approaches three-fourths of adults (72%) (Figure 10). Participation rates are particularly high in Seychelles (91%), Sierra Leone (89%), and Liberia (89%), while fewer than half of citizens say they voted in Morocco (49%), Gabon (48%), Sudan (42%), Côte d’Ivoire (41%), and Cameroon (41%). o The youngest adults (63% of 18- to 35-year-olds) are far less likely to say they voted than older cohorts (78%-84%). Reported voting rates are also relatively low among women, urban residents, and the most educated respondents, and are far lower in North Africa and Central Africa (both 51%) than in other regions (72%-79%) (Figure 11).

- Fewer than half (42%) of Africans believe that their country’s elections ensure that members of Parliament (MPs) represent the views of voters. A similar minority (45%) say their elections enable voters to remove leaders from office who fail to align with the desires of the people (Figure 12). o These assessments have remained fairly stable over the past eight years (Figure 13).

- Tanzania (64%) and Ghana (62%) register the highest levels of confidence that elections ensure representation, while fewer than one in five citizens in Gabon (17%) and Eswatini (18%) agree (Figure 14). Interestingly, some countries often recognised for high levels of democratisation record below-average levels of confidence in the efficacy of elections in ensuring representation, including Botswana (25%), Cabo Verde (34%), Mauritius (36%), and Seychelles (39%).

- Confidence that elections enable voters to replace non-performing leaders is strikingly low in Gabon (14%), where the Bongo family succession lasted 55 years before being terminated by a coup d’état in August 2023, and in Eswatini (15%), where a constitutional monarchy has resisted demands for political reform. Even though Mauritius and Botswana are touted as democratic models, only one-third of their citizens (34% each) see their elections as empowering voters to unseat incumbents. In contrast, the strongest faith in this function of elections is expressed in Ghana (80%), which has witnessed multiple changes in both head of state and ruling party, and the Gambia (72%), where 22 years of dictatorship ended with electoral defeat and exile for Yahya Jammeh (Al Jazeera, 2017). o Perceptions that elections guarantee representation are particularly weak among the most educated citizens (37%) and citizens in Central African countries (30%) (Figure 15). The pattern is almost identical with regard to the view that elections enable voters to remove non-performing leaders.

- Africans overwhelmingly say they feel “completely free” (65%) or “somewhat free” (20%) to vote for the candidate of their choice without feeling pressured. Only 14% indicate that they feel pressured or constrained (Figure 16). o This sense of freedom is almost universal (97% “completely” or “somewhat” free) in the Gambia, Zambia, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania. It is far less widespread in Ethiopia and Eswatini, where only 28% and 35%, respectively, feel “completely free” (Figure 17). o West Africans are most likely to say they feel somewhat/completely free to vote as they wish (90%), while Central Africans feel least free (75%) (Figure 18).

- Six out of 10 Africans say their most recent national elections were “completely free and fair” (37%) or “free and fair with minor problems” (23%). However, one-third (34%) of respondents report that their elections were “not free and fair” or “free and fair with major problems” (Figure 19). o These assessments vary by more than 60 percentage points across countries, ranging from just one-fourth of Gabonese (24%) and Sudanese (25%) to almost nine out of 10 Tanzanians (87%) and Liberians (85%) who say their elections were generally free and fair (Figure 20). o Perceptions that elections have been free and fair are far less common in Central and North Africa (37% and 40%, respectively) than in other regions (59%-66%). Rural residents, older citizens, and less educated respondents are more likely to see their elections as free and fair than urbanites, younger, and more educated respondents (Figure 21). o On average across 31 countries surveyed consistently since 2014/2015, the perception of elections as generally free and fair has declined from 64% to 58% (Figure 22).

- On two other indicators of the election environment – ballot secrecy and personal safety – a majority of Africans see little cause for concern. Still, significant minorities think it’s possible for powerful people to find out how they voted (30%) and report experiencing “some” or “a lot” of fear of intimidation or violence during their most recent election (21%) (Figure 23). o Doubts about ballot secrecy are especially high in Sudan (53%) and Cameroon (52%), while fewer than one in six respondents share this concern in Sierra Leone (16%), Zambia (15%), Gambia (15%), and Tanzania (13%) (Table 1). o Close to half of respondents in Guinea and Uganda (47% each) report fearing intimidation or violence during their last election – about 10 times as many as in Mauritius (5%), Morocco (5%), and Madagascar (4%).

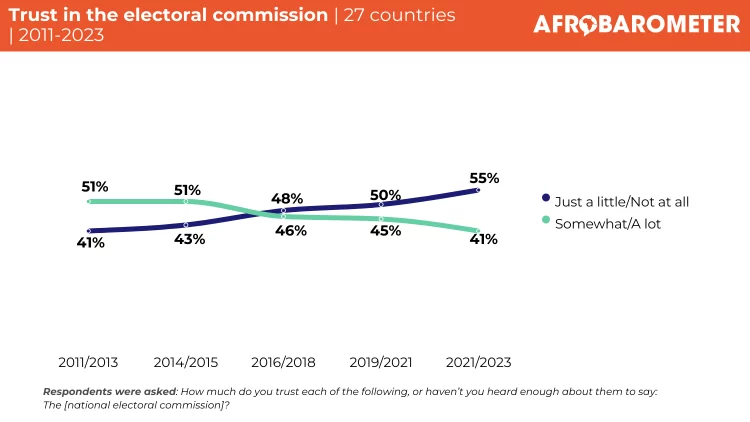

- Moreover, public trust in the agency charged with organising and managing elections is fairly weak in most countries (Figure 24). On average, only four in 10 citizens (39%) say they trust their national electoral commission “somewhat” or “a lot,” while 57% express little or no trust. Tanzania is an outlier, with 79% of citizens expressing trust in the electoral commission. Fewer than one in four respondents say the same in Gabon (16%), Angola (21%), Eswatini (22%), Congo-Brazzaville (23%), and Nigeria (23%). o Trust in the electoral commission is particularly low among urban residents (35%), young people (37%), citizens with secondary or post-secondary education (35%), and Central Africans (24%) (Figure 25). o On average across 27 countries where this question was asked consistently since 2011/2013, trust in the electoral commission has dropped by 10 percentage points, from 51% to 41% (Figure 26).

The year 2024 promises a bumper crop of elections in Africa. National contests are planned in 23 African countries, from Comoros’ presidential election in January to Ghana’s in December (EISA, 2024; Chemam, 2024).

Even smooth elections are times of high stakes and tension that can put democratic processes to the test. And Africa’s elections haven’t always been showcases of smooth organisation, free and fair playing fields, and universally accepted outcomes (Gueye, 2009; M’Cormack-Hale & Dome, 2022). The past decade has seen a multitude of challenges to democratic norms in the pursuit of power, from incumbents manipulating constitutions to stay in power, repression of legitimate campaign activities, and pre- and post-election violence to electoral fraud and coups d’etat. Just since 2020, the continent has seen nine successful coups, six of them in West Africa and eight in French speaking countries (AJLabs, 2023; Africanews, 2023; Adekoya, 2021; Freedom House, 2019; Mbulle-Nziege & Cheeseman, 2022; Institute for Security Studies, 2023; Zounmenou & Adam, 2021; Darracq & Magnani, 2011).

Such irregularities and abuses continue despite attempts by regional organisations to reinforce democratic processes. For example, the Economic Community of West African States (2001) Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance provides that any constitutional or election-law reforms within six months of an election should require consensus by all sides, but political players often bypass this provision.

While elections are just one aspect of democracy (Lindberg, 2006), they draw immense public attention, and poorly managed, unfair, or contentious elections may undermine citizens’ trust in elections and the workings of democracy (Afrobarometer, 2023; M’Cormack Hale & Dome, 2022a, b; Bratton & Bhoojedhur, 2019; Penar, Aiko, Bentley, & Han, 2016; Penar, 2016; Darracq & Magnani 2011; Zounmenou & Adam, 2021).

Efforts by the political class and electoral bodies to shore up public confidence in elections often involve complex and costly control systems, such as electronic voting in Nigeria, that have pushed the per-capita cost of African elections to more than double the global average without ensuring elections that are widely seen as legitimate (Sawyer, 2022).

As citizens across the continent enter a busy electoral season, how do they perceive the quality and efficacy of their elections?

Findings from Afrobarometer’s Round 9 surveys in 39 African countries show that while most Africans endorse elections as the best method for choosing their leaders, this preference has weakened over the past decade. Most feel free to vote as they choose, and they assess their most recent election as largely free and fair, but fewer than half think voting ensures representative, accountable governance. And public trust in national electoral management bodies is weak in most countries.