- Mozambicans are critical of the quality of their elections: Only about half (52%) say their most recent national election was free and fair, the lowest level since 2008, and only one in three believe that votes are “always” counted fairly (32%) and that opposition parties are “never” prevented from running (33%).

- While a strong majority (78%) see voting as a civic duty, citizens are becoming increasingly accepting of choosing leaders through methods other than elections (27%, up from 17% in 2012).

- Fewer than half (45%) of Mozambicans say they prefer democracy over any other system – the lowest level since 2002, and the second-lowest among all 36 African countries surveyed in 2014/2015. Growing numbers of citizens see non-democratic alternatives as acceptable

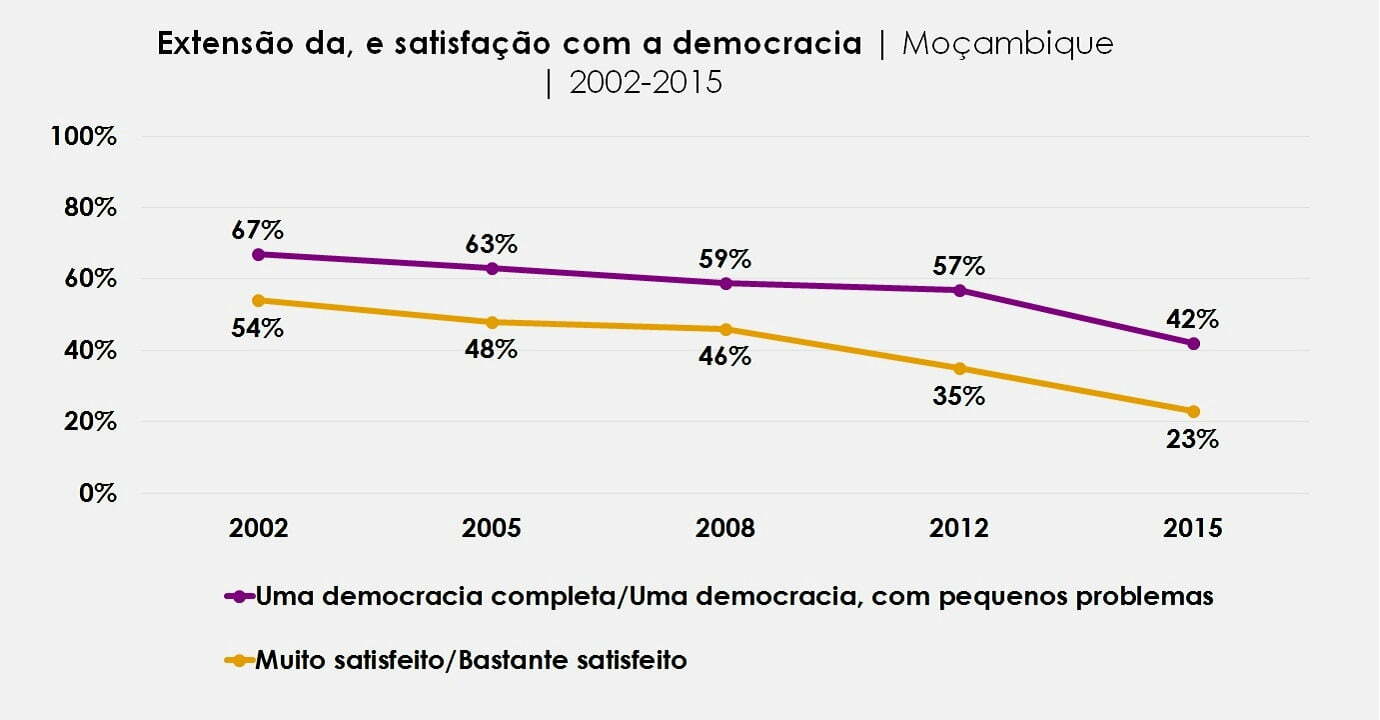

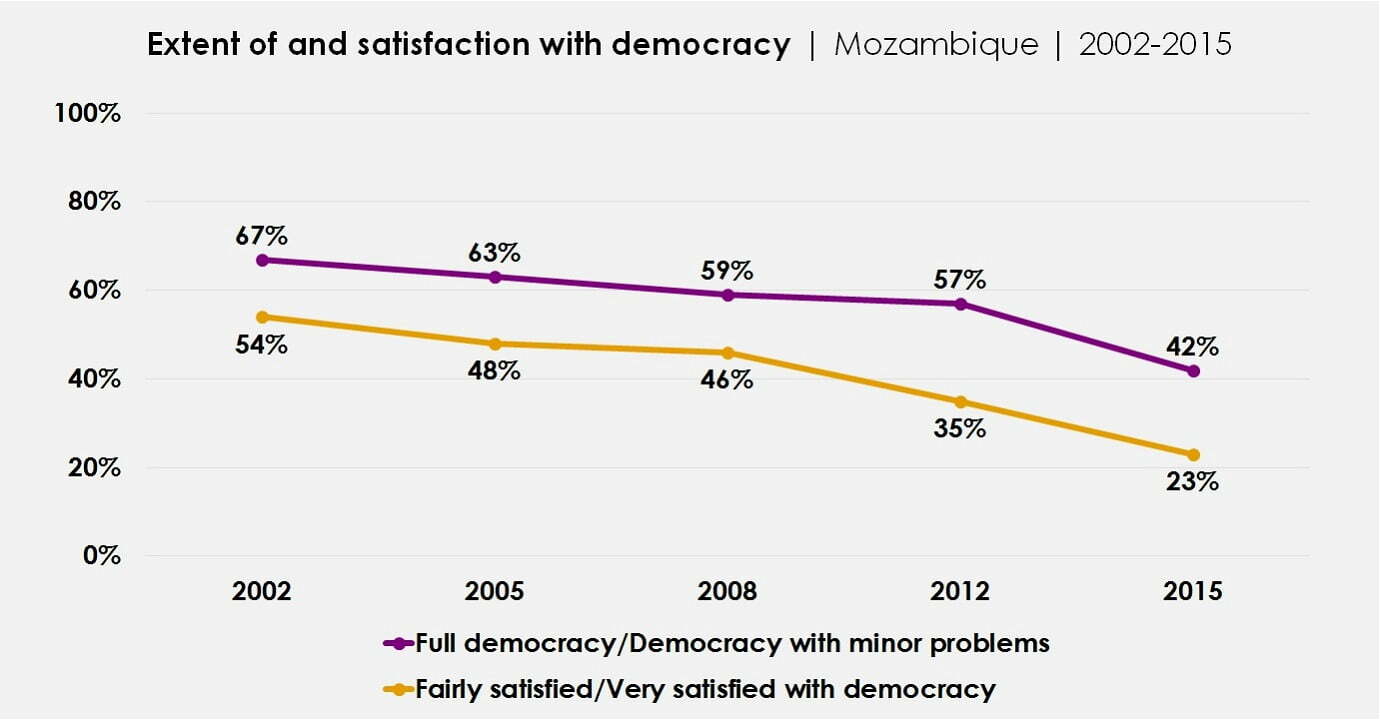

- The proportion of citizens who consider Mozambique “a full democracy” or “a democracy, but with minor problems” has declined to 42%, and only one in four respondents (23%) say they are satisfied with the way democracy works in their country – less than half the level of satisfaction recorded in 2002.

- Only minorities believe that elections work well to ensure that the Assembly of the Republic reflects citizens’ views (42%) and that voters can remove underperforming leaders from office (32%).

ALSO AVAILABLE IN PORTUGUESE.

Since independence in 1975, Mozambique’s history has been marked by deep economic crises, political instability, and widespread human-rights violations. In 1990, after 16 years of civil war between the governing Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO) and the Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO), the government of former President Joaquim Alberto Chissano established a democratic constitution in an effort to end the conflict (Pitcher, 2006). The constitution foresees multiparty elections and the separation of legislative, executive, and judiciary powers.

Economic and political reforms to support a transition to democracy won praise from independent observers. However, elections in 2005, 2009, and 2014 were marred by charges of electoral manipulation (Bertelsen, 2016; Azevedo-Harman, 2015), raising questions about Mozambique’s progress toward peace and democracy.

Using data from Afrobarometer’s 2015 survey, this dispatch examines how ordinary Mozambicans perceive the quality of their elections and the current state of their country’s democracy. Survey responses paint a troubling picture, suggesting an alarming decline in popular confidence in elections and democracy. Fewer than half of respondents see democracy as preferable to any other form of government, and acceptance of authoritarian alternatives is on the rise. Increasing numbers of citizens see their elections as less than free and fair and doubt that elections ensure that voters’ views are represented. Still, most Mozambicans see voting as a good citizen’s duty – perhaps an indication that despite high current levels of dissatisfaction, they have not entirely given up on democracy.