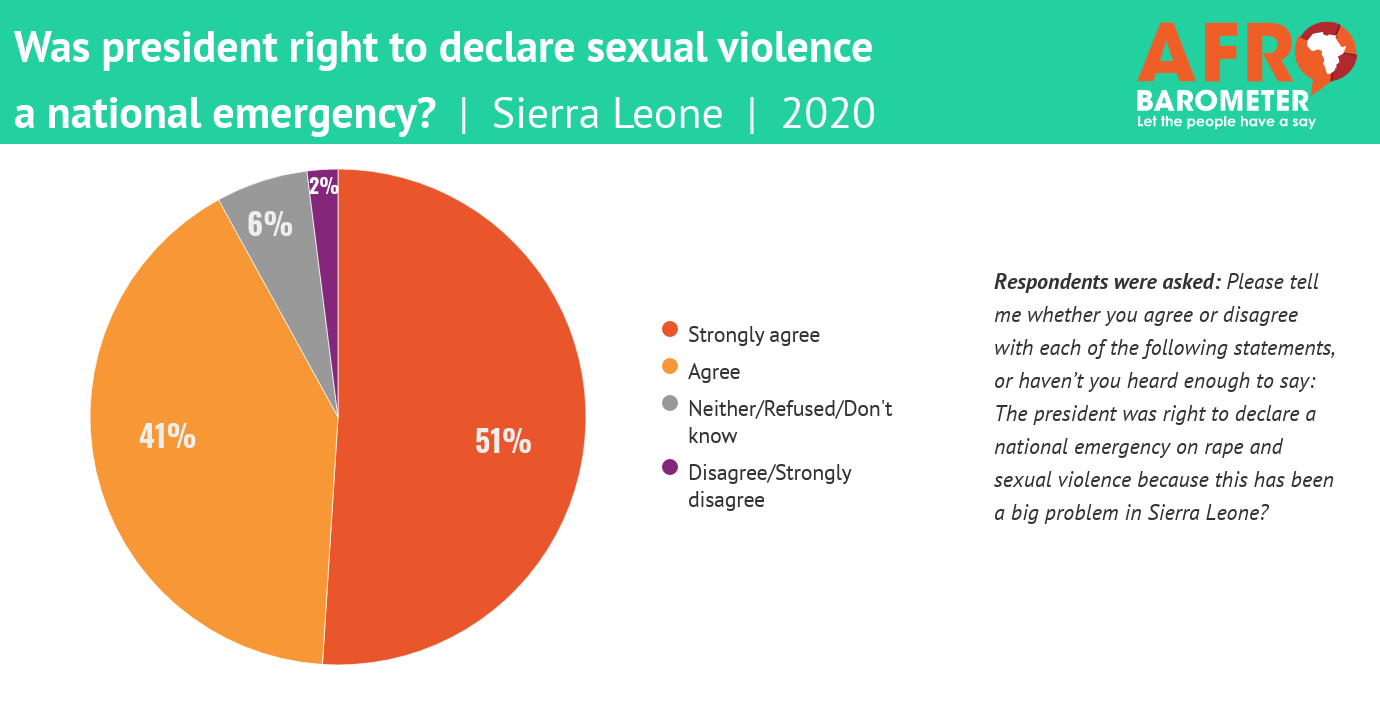

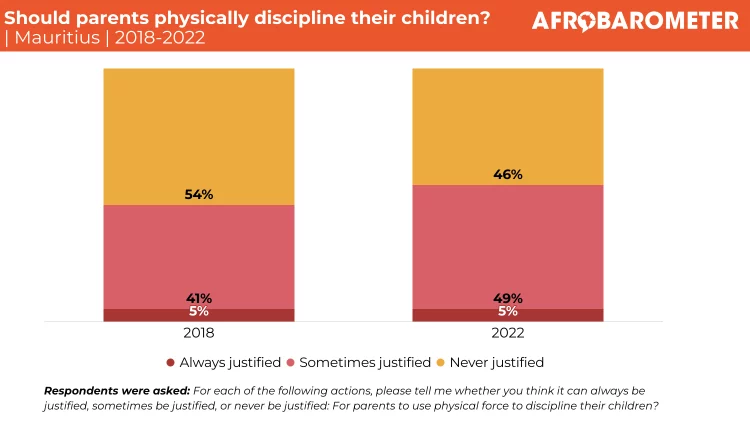

- Africans see gender-based violence (GBV) as the most important women’s-rights- related issue that their government and society need to address, followed by too few women in influential positions in government, unequal access to education, and unequal opportunities in the workplace. Almost four in 10 citizens (38%) say GBV is “somewhat common” or “very common” in their community.

- A sizeable and (slowly) growing majority (75%) of citizens say women should have the same chance of being elected to public office as men. But more than half (52%) say that a woman who runs for office is likely to be criticised or harassed. Women are still consistently less likely than men to join in many forms of civic engagement, including voting.

- On average across 39 African countries, women are less likely than men to have secondary or post-secondary education (51% vs. 59%), a gap that is even wider among the youngest citizens, although their levels of educational attainment are also higher.

- Almost three-quarters (73%) of Africans say women should have the same rights as men to own and inherit land, though support for equality varies from just 31% in Mauritania to 92% in Cabo Verde. A narrower majority (58%) endorse women’s equal right to jobs, again varying widely by country. About seven in 10 citizens (69%) say women in fact enjoy equal rights when it comes to jobs, but fewer (63%) say the same about land ownership.

- Women trail men significantly in ownership of key productive and informational assets such as motor vehicles (15% vs. 31%), radios (50% vs. 65%), and bank accounts (34% vs. 43%). Similarly, women are less likely than men to say they make household financial decisions themselves (35% vs. 44%).

- Governments get relatively positive marks for their efforts to promote gender equality, but nearly two-thirds (63%) of citizens say their governments should be doing more.

Everywhere we look, we are reminded that gender equality is a cornerstone of Africa’s development. The African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063 identifies “full gender equality in all spheres of life” as one of its core goals. Under this goal, outcomes targeted for achievement by 2023 include removing all obstacles to women’s ownership and inheritance of property, contracting, and ownership of bank accounts; ensuring that at least one in five women have control of productive assets; and reducing violence against women by at least one-third (with elimination to be achieved by 2063) (African Union, 2015a, b).

Similarly, the United Nations’ (2016) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) highlight the centrality of gender equality both as a goal in its own right (SDG#5) and as a thread woven throughout the SDG goals, targets, and indicators.

We see evidence of at least some measure of commitment to these goals across the continent. Forty-four African states have ratified the 2003 Maputo Protocol on the rights of women in Africa, which has just celebrated its 20th anniversary (African Union, 2003, 2023). Similarly, 52 African states have ratified the United Nations (1979) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and all UN member states are enjoined to pursue the SDGs.

Yet gender-equality advocates also recognise that reality is still far from matching up with these lofty aspirations. Change, while real, is often slow and uneven; gaps persist even as both men and women make gains in educational attainment, in access to technology and information, and in the workplace.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), for example, reports that girls are still more likely to be out of school than boys (UNECA, 2023), due not only to families’ lower prioritisation of girls’ education but also to factors such as child marriage and gender based violence (Savedra & Brixi, 2023; African Development Bank & UNECA, 2020). On the World Bank’s (2020) Women, Business and the Law Index, Africa’s score inches upward, suggesting that economic and legal equality is still many years away. The Equal Measures 2030 (2022) SDG Gender Index, which tracks gender-equality indicators for 14 SDGs, describes progress in Africa as “slow and patchy.”

Afrobarometer offers a citizens’ perspective on gender equality in Africa, based on a special module included in Round 9 surveys in 39 countries between late 2021 and mid-2023. Our findings, too, suggest slow progress alongside persistent challenges. In principle, most Africans are on board with the goals of gender equality, and many even report that equality in employment and land rights is largely a reality.

But in data on women’s lived experience – their educational attainment, their employment status, their control over resources – the gender gaps are still there, often showing little change over the past decade (see e.g. Lardies, Dryding, & Logan, 2019). Support for women in politics confronts expectations of community backlash. Even physical security remains a top-of-mind concern: Gender-based violence ranks as the No. 1 women’s-rights issue that Africans say their government and society must address.

In short, turning stated support for equality into a reality embedded in law, in social acceptance, and in everyday practice still appears to be a long-term undertaking. One encouraging note: Majorities of Africans say both that their governments are doing reasonably well at addressing gender equality and that they need to do more, recognising that the job is far from finished.