- More than four in 10 South Africans (43%) say China’s economic activities have “a lot” of influence on the country’s economy. o About three in 10 (31%) say they “don’t know” enough to assess China’s economic influence.

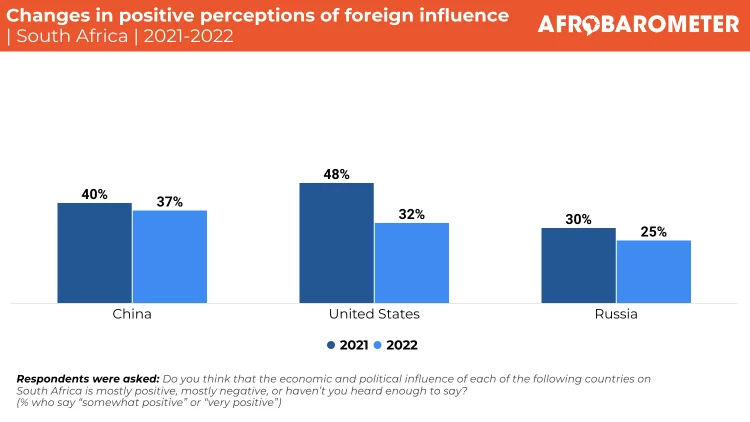

- Positive perceptions of foreign influence have decreased since 2021, including a 16- percentage-point drop for the United States.

- Still, positive outnumber negative perceptions by roughly 2-to-1 regarding the economic and political influence of China (37% positive vs. 20%), the United States (32% vs. 15%), and the EU (20% vs. 14%). o Assessments of Russian influence are almost equally negative (22%) and positive (25%).

- ANC supporters are no more likely than adherents of other political parties to see Russia’s influence as positive. Adherents of the ANC and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) are most likely to see China’s influence as positive, while Democratic Alliance (DA) supporters favour U.S. influence. o Large shares of citizens say they “don’t know” enough to assess the influence of foreign powers, especially the EU.

Emboldened by the rise of a multipolar world order, South Africa’s political elite is increasingly caught between its allegiance to traditional Western allies – whose values represent the national ambition and are enshrined in the Constitution of a liberal democratic order – and emerging powers such as China and Russia, the former representing a key economic partner and the latter having fostered a warm relationship with the African National Congress (ANC) leadership during the Cold War and the apartheid resistance movement (Chan, 2023).

As this global reorientation evolves, South Africa finds itself at a critical juncture that necessitates a recalculation of its alignment to foreign powers. The recent allegation by the United States that a South African navy vessel carried weapons to Russia in aid of its war in Ukraine brought into clear focus the consequences of alignment without calculation (Khumalo, 2023). Not only did the incident cause the South African rand to tumble to its lowest trading value yet, but it also threatened broader trade relationships with the United States, including the extension of the favourable African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). South African exports to the United States, one of South Africa’s largest trading partners, represented 8.8% of total exports in 2022, eclipsed only by exports to China (9.7%) (International Trade Centre, 2023), while trade with Russia represents a fraction of U.S. or China trade (Cohen, 2023).

More broadly, the calculus affects the investment climate in South Africa. Already alarmed by the country’s electricity crisis, low growth prospects, and mounting crime rates, investors will likely add a geopolitical risk premium to their assessments. An added layer of complexity was created around the conference of BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) in August when South Africa, the conference host, faced pressure to take action against Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose wanted status by the International Criminal Court divided opinion on the necessity for his in-person attendance. In July, a month before the conference was set to kick off, South Africa’s government announced that by mutual agreement Putin would attend the conference virtually, represented in person by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov (Bartlett, 2023).

Does the government’s drift toward the Sino-Russian orbit represent the views of South Africans? Given that the Russian alliance is driven by the ANC elite, do ANC supporters see Russian influence as positive? And where do South Africans stand on the influence of the country’s traditional Western allies and core investment partners such as the United States and European Union (EU)?

Related content