- Knowing your local councillor: Seven in 10 Ugandans (70%) were able to correctly identify their local government councillors in a 2005 survey – well above an 18-country average of 46%. Men, more educated citizens, and committed democrats and partisans were particularly likely to know their councillor’s name.

- Contacting local councillors: Between 2005 and 2022, the share of Ugandans who contacted a local councillor during the previous year dropped from 62% to 25%.

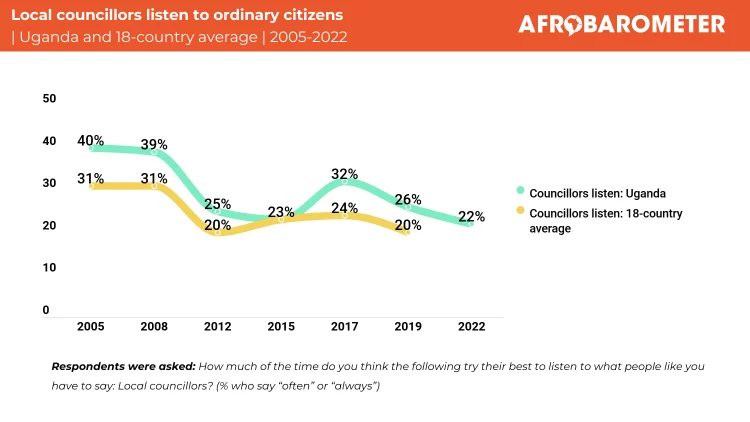

- Councillor responsiveness: In 2005, 40% of Ugandans said that councillors “often” or “always” try their best to listen to what citizens have to say. This number dropped to 22% in 2022. Although Ugandan councillors seem to have been more responsive than most of their counterparts in other African countries, this gap has narrowed over time.

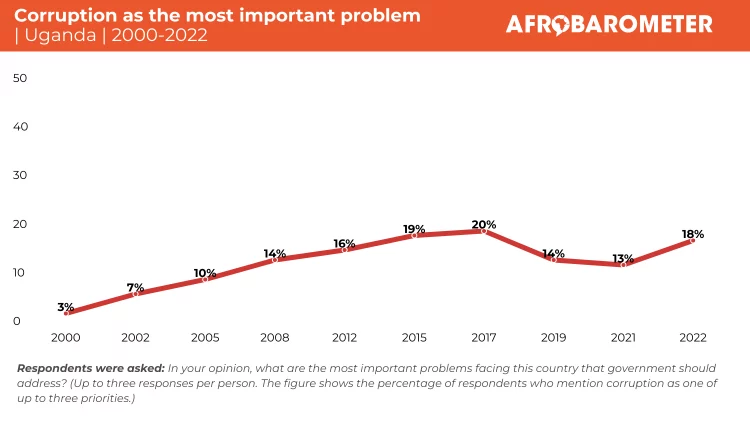

- Local government corruption: About four in 10 Ugandans (39%) say that “most” or “all” local government councillors are corrupt, a perception that has been fairly stable over time.

- Local government performance: Public approval of local government councillors’ performance has dropped from 71% in 2005 to 54% in 2022. Fewer than half of Ugandans are satisfied with how local governments provide basic services, and even fewer are satisfied with their financial management and transparency.

- What matters most for performance evaluations of local councillors? Citizens who see their local government councillors as corrupt and unwilling to listen to their concerns are least likely to be satisfied with councillors’ performance. In contrast, contacting a councillor has a positive effect on performance evaluations.

In January 2021, Ugandans elected local government councillors for the fifth time since the 1997 Local Governments Act provided for the formation, setup, and functions of local government councils (Republic of Uganda, 1997).

Key aims driving the legislation regulating local government in Uganda were to create decentralised local structures that would be better at providing services to people and would help ensure good governance, democratic participation, and citizen control over decision-making (Republic of Uganda, 1995, 1997).

Through the devolution of functions, powers, and services from the national to the local level, local government councils (or district councils) became responsible for a variety of tasks in their jurisdictions, including financial management and oversight, representation of citizens, legislation, development of strategic plans, and monitoring the performance of government employees and the provision of government services (Adoch, Emoit, Adiaka, & Ngole, 2011). These functions are in part undertaken by political leaders directly elected at all levels of local government, including local government councillors, who are charged with ensuring that government services are effectively delivered to their electorate.

As is true of members of Parliament, the number of local government councillors has increased dramatically over the past two decades due to the creation of new districts, city councils, municipalities, town councils, and sub-counties. While some prominent political leaders argue that additional lower administrative units are necessary to satisfy citizens’ demands and bring services closer to the people, others argue that they unnecessarily strain the government’s coffers (Monitor, 2021; Independent, 2021) and constitute a form of political patronage (Green, 2010).

As Figure 1 shows, the number of districts has increased drastically since the enactment of Uganda’s new Constitution and the Local Governments Act in the mid-1990s, and so has the country’s population. Although this suggests that increasing the number of districts is necessary to ensure that the delivery of services is “close to the people,” previous research (e.g. Greene, 2010) and an analysis of where the districts have been created (see below) suggest that this process is less driven by demographic changes than by political arithmetic.

While this policy paper is not intended to settle this debate, we provide new empirical evidence to answer several important related questions: Are local government councils and their representatives accessible to their constituents? How satisfied are citizens with the performance and responsiveness of their elected local government councillors? And how have citizens’ evaluations changed over time?

We show that a majority of Ugandans know who their local government councillors are, though fewer and fewer citizens contact them. Our data also reveal that citizens are becoming increasingly disenchanted with their political representatives, think they do a poor job of listening to constituents’ concerns, and perceive many of them as corrupt. The proportion of Ugandans who are satisfied with the performance of their local government councillors has dropped significantly since 2005, and fewer than half of citizens rate their local government positively on the provision of basic services, financial management, and transparency.

A broader finding that emerges from our statistical analysis is that citizens’ experiences with councillors are far more important drivers of their performance evaluations than their personal circumstances. The upshot of this finding is that councillors have it in their hands to improve their relationship with their constituents.

Throughout the paper we also compare Ugandans’ relationship with their councillors to that of their peers elsewhere in Africa. It is striking that despite many of the negative trends over the past 15 years, Ugandans have not only been more likely than citizens in other African countries to know and engage with their councillors, but also more inclined to hold them accountable between elections. Similarly, Ugandan councillors have been seen as more responsive to citizens’ needs and received better overall performance evaluations than their counterparts in most other countries. There is little cause to celebrate, however, as Uganda’s comparatively high ranking seems to be at least in part a result of a continent-wide deterioration of citizen-councillor relationships.

Lastly, we conduct a preliminary analysis of whether citizens in less populous districts are more satisfied with their councillors’ performance than citizens in more populous districts. In contrast to what proponents of decentralisation and the creation of new districts would expect, we find no meaningful difference – a result that casts doubt on the argument that decentralization has a universally positive effect on local governance, at least as it is currently implemented in Uganda.