- Seven out of 10 Zimbabweans (70%) say the media should have the right to publish any ideas and views without government control.

- Almost two-thirds (63%) of citizens believe that the news media should constantly investigate and report on government mistakes and corruption.

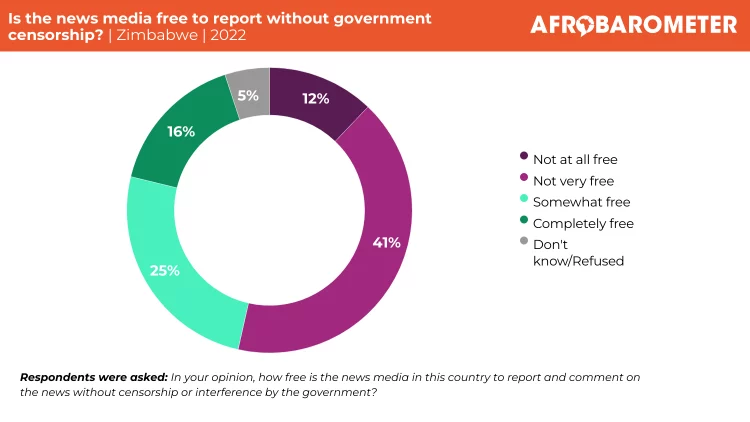

- A slim majority (53%) say the news media in Zimbabwe is “not very free” or “not at all free’’ to report and comment on news without censorship or interference by the government.

- Majorities endorse the right of ordinary citizens and the news media to access government information on budgets and expenditures for local government councils (79%), bids and contracts with companies competing for government-funded projects or purchases (71%), and salary information for teachers and local government officials (54%).

- Radio remains the top source of news for Zimbabweans: 65% say they tune in at least a few times a week. Social media occupies the second spot (41%), followed by television (28%), the Internet (25%), and newspapers (8%).

While the World Press Freedom Index says media freedom in Zimbabwe has improved “slightly” since Robert Mugabe’s reign, a new government measure may call its progress into question. The so-called “Patriot Bill,” approved by Parliament in late May, calls for lengthy prison sentences – and in some cases the death penalty – for anyone who attends a meeting where sanctions, boycotts, anti-government subversion, or armed intervention are discussed. Critics say the bill promotes self-censorship by threatening journalists who cover meetings with dire consequences (Reporters Without Borders, 2023a, 2023b).

The Constitution protects freedom of the media and of expression, including citizens’ right to “seek, receive and communicate ideas and other information” (Dube, 2019; Mugari, 2020). The media landscape is still dominated by the state-owned Herald newspaper and Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation, although fast-growing digital media provides platforms for citizens to exchange information and alternative narratives (Chirimambowa & Chimedza; 2022; Chimhangwa, 2022). Weekly media briefings after Cabinet meetings, instituted by President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s government, have greatly improved citizens’ access to official information on a regular basis, providing an opportunity for journalists from both private and public media houses to interact directly with government officials on matters of public concern.

But even without the “Patriot Bill,” the media space has been a hard-hat area for media practitioners. The Official Secrets Act and the Cyber Security and Data Protection Act are widely seen as impediments to the work of journalists (Matsengarwodzi, 2022). Journalists are also under pressure to align with either the ruling party or the opposition, a polarisation that does not promote freedom of expression. The Media Institute for Southern Africa (2022) notes that 2020 and 2021 saw 52 and 22 cases, respectively, of journalists being harassed or assaulted by the police or the army while performing their duties. Reporters Without Borders (2023) ranks Zimbabwe 126th out of 180 countries in media freedom.

Afrobarometer survey findings show that most Zimbabweans want a media that is free from government interference and that serves as a watchdog over government, investigating and reporting on its mistakes and corruption. But only a minority think the country currently has a free media.

Majorities also endorse the right of ordinary citizens and the media to access various types of government information, including budgets and expenditures for local government, bids and contracts, and salary information for teachers and local government officials.

Radio is still king among sources of news in Zimbabwe, though social media is challenging its dominance among young, urban, and educated citizens.