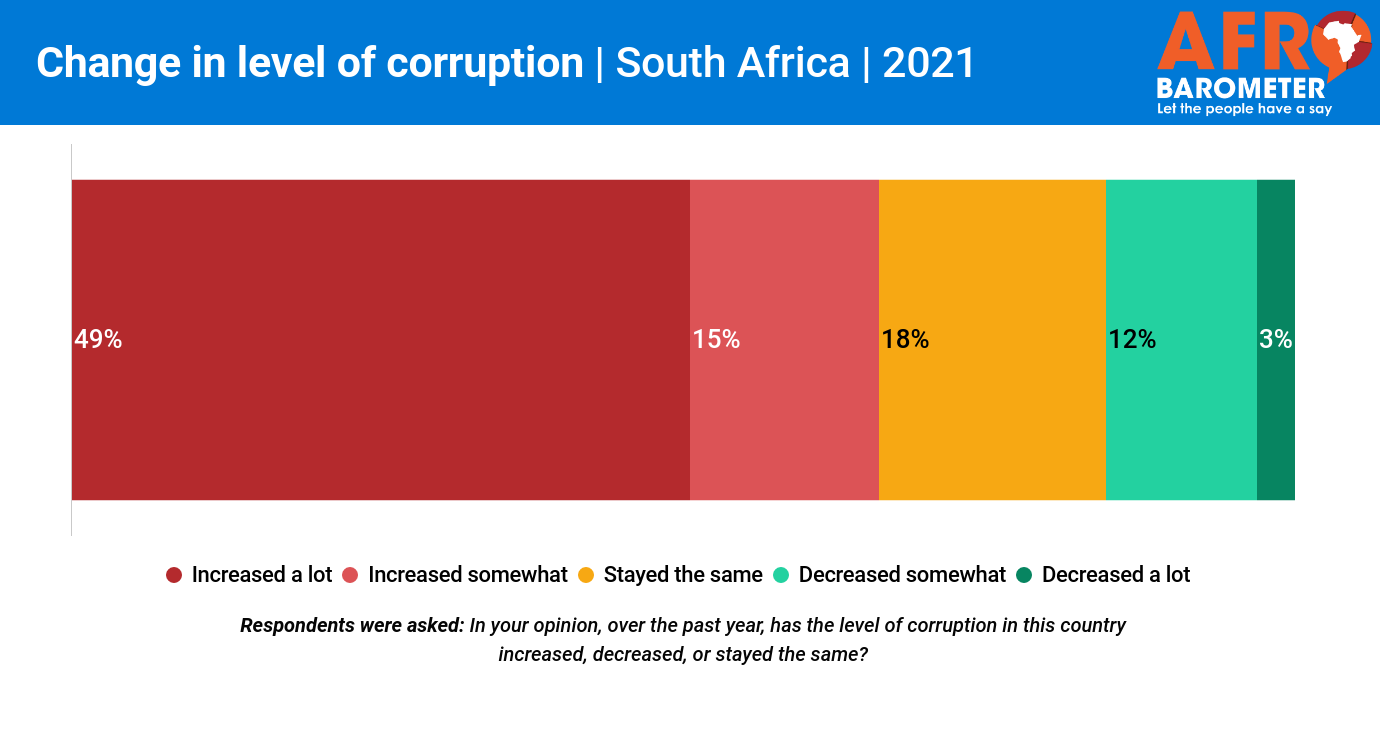

- Almost two-thirds (64%) of South Africans say that corruption increased in the past year, including half (49%) who believe it increased “a lot.”

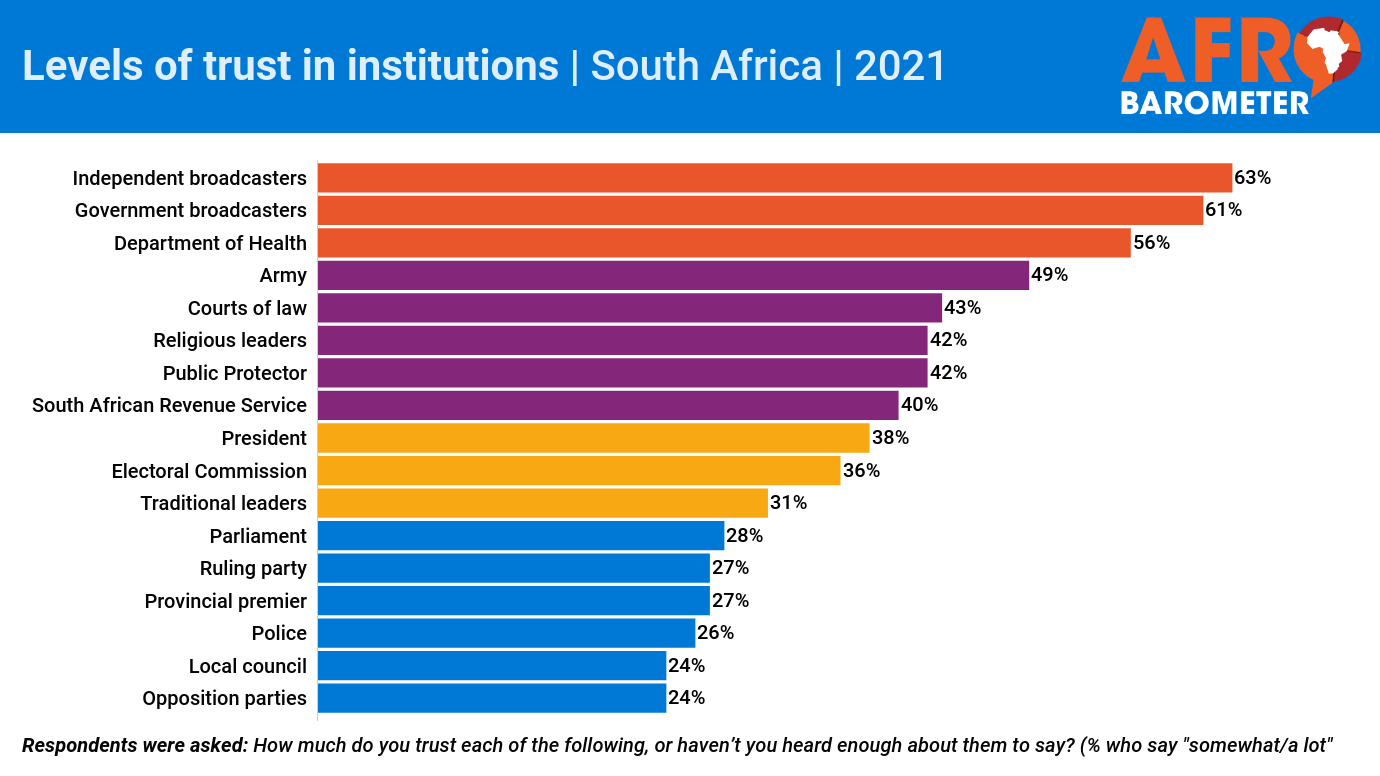

- State institutions are widely seen as corrupt. Half or more of citizens say “most” or “all” officials are involved in corruption in the police (56%), the president’s office (53%), local government councils (51%), and Parliament (50%). Non-governmental organizations, traditional leaders, and religious leaders are less commonly seen as corrupt.

- Three-fourths (76%) of South Africans say the government is performing “fairly badly” or “very badly” in the fight against corruption,

- Among citizens who interacted with key public services during the past year, substantial proportions say they had to pay a bribe to avoid a problem with the police (24%) or to obtain a government document (21%), police assistance (15%), public school services (10%), or medical care (8%).

- Three out of four South Africans (76%) say people risk retaliation or other negative consequences if they report incidents of corruption, a 13-percentage-point increase compared to 2018.

- ▪ Seven in 10 citizens (71%) believe that officials who break the law “often” or “always” go unpunished, while half (49%) say ordinary people who commit crimes enjoy such impunity.

Perceptions of pervasive corruption in South Africa have dominated public discourse for the better part of the past decade. In its many forms, corruption undermines the effectiveness of the state, worsens the quality of public services, and ultimately erodes public trust (Fukuyama, 2014). In South Africa, former President Jacob Zuma and some of his allies stand accused of state capture – the use of the state for personal interests that has crippled various compromised institutions (February, 2019). During the latter part of Zuma’s tenure, public opinion was largely negative on indicators of service delivery (Nkomo, 2017), trust (Chingwete, 2016), and the responsiveness of democratic institutions (Dryding, 2020).

In 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa’s promises to restore government integrity, strengthen democratic institutions, and fast-track development gave South Africans a renewed sense of hope (Hendricks, 2019). To tackle corruption, his administration improved independent oversight and presented an extensive new National Anti-Corruption Strategy that calls on all stakeholders to take responsibility for ethical leadership (Republic of South Africa, 2020).

Three years into Ramaphosa’s tenure, what impact has his government had on corruption?

Transparency International’s (2020) most recent Corruption Perceptions Index scored South Africa at 44 out of 100 points, just a 1-point improvement from 2017. In 2020, the government was accused of misappropriating COVID-19 relief funds (Auditor-General of South Africa, 2020). Evidence of irregularities in the awarding of tenders related to COVID-19 response efforts (McCain, 2021) has engulfed the Department of Health in a scandal that led to the resignation of Minister of Health Zweli Mkhize hours before a cabinet reshuffle (Tandwa, 2021). And corruption again made the news with the recent murder of a whistle-blower in the Gauteng Health Department (Klein, 2021).

New Afrobarometer survey findings from 2021 mirror the headlines: Not only do South Africans believe that corruption is getting worse, but they also see large portions of elected officials and civil servants as involved in corrupt activities. Society says the government is handling the anti-corruption fight badly, while channels to report corruption are increasingly seen as unsafe.