- A majority (56%) of Nigerians say the level of corruption in the country increased “somewhat” or “a lot” during the past year.

- Six in 10 respondents (61%) say “most” or “all” police officials are corrupt, an improvement from previous survey rounds. About four in 10 citizens see widespread corruption among elected officials and judges, while traditional and religious leaders are least commonly seen as corrupt (by 26% and 30%, respectively).

- Religious and traditional leaders are also considered the most trustworthy leaders in Nigeria, trusted “somewhat” or “a lot” by 61% and 54% of citizens, respectively. They outrank elected officials, including the president (39%), as well as the army (44%) and the courts (33%).

- Among Nigerians who had contact with key public services during the previous year, a large majority say they had to bribe the police at least once to get help (76%) or avoid a problem (68%). Four in 10 (40%) say they paid a bribe to obtain a government document, while a quarter or fewer paid a bribe for school services (25%) or medical care (21%).

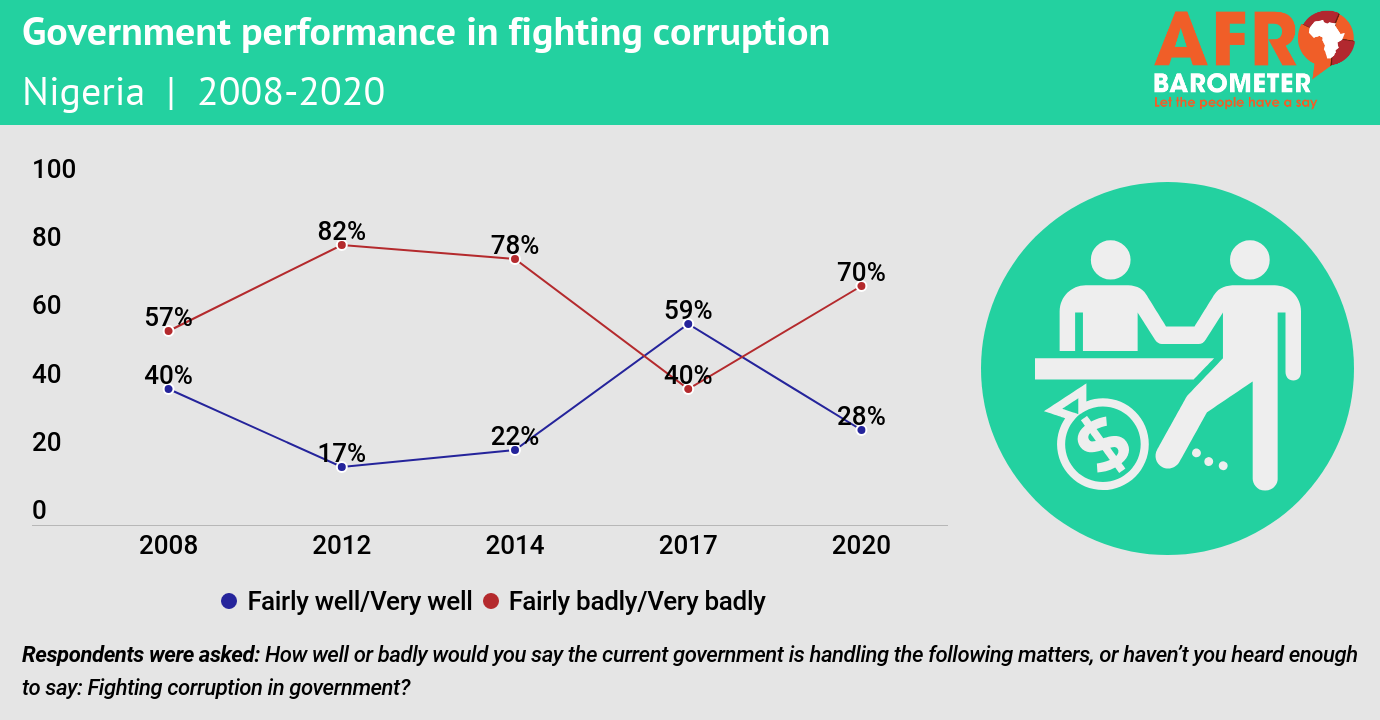

- Fewer than three in 10 citizens (28%) say the government is doing “fairly well” or “very well” in fighting corruption, half the proportion who approved of the government’s performance in 2017 (59%).

- Eight in 10 Nigerians (83%) say ordinary citizens risk retaliation or other negative consequences if they report incidents of corruption to the authorities, up from 77% in 2017.

Since assuming office in May 2015, the administration of President Muhammadu Buhari has taken several measures to curb corruption. These include the establishment of the Presidential Advisory Committee Against Corruption (PACAC), prosecution of high-profile corruption cases, suspension of top government officials alleged to be involved in corrupt practices, adoption of a whistleblower protection policy, and enhanced capacity building programs for officers of anti-corruption agencies such as the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC), and the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB).

These efforts have chalked up some successes, including the recovery of about N71.7 billion ($184 million) by the federal government since the whistleblower policy was inaugurated in December 2016 (Daily Times, 2017). Even so, critics express distrust in the government’s anti-corruption campaign, voicing concerns about possible abuse of the whistleblower policy, institutional weaknesses, and perceived discrimination and lack of transparency in the management and distribution of COVID-19 funds and palliatives (Action Aid, 2020; Vanguard, 2020). Some highly placed law enforcement agents have been accused of routinely converting funds recovered from corruption cases for their personal use; the acting chairman of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission was recently suspended based on such an allegation (Africa Report, 2020). A study has found that some “structural and facility-level corruption and accountability issues” hinder health workers’ efforts to fight the COVID-19 pandemic (Conversation, 2020).

Findings from the most recent Afrobarometer survey, conducted in early 2020, show that a majority of Nigerians perceive an increase in the level of corruption in the country, and the approval rating for the government’s performance in fighting corruption has declined sharply. Large majorities of citizens endorse the media’s watchdog role over government but do not feel safe reporting corrupt acts themselves.

Related content