- Among key public officials in Ghana, the police, judges and magistrates, members of Parliament, civil servants, and tax officials are most widely perceived as corrupt. Perceived corruption among the police has declined slightly compared to 2017.

- Still, the police are the institution that the largest number of citizens report bribing to access services. Among those who had contact with key public services during the previous year, four in 10 say they paid a bribe to avoid problems with the police (42%) or to obtain police assistance (39%).

- The army, religious leaders, and the presidency are the most trusted public institutions (by 72%, 63%, and 58%, respectively, who say they trust them “somewhat” or “a lot”). Opposition political parties (37%), local government officials (38%), and tax officials (39%) are least trusted.

- More than half (53%) of Ghanaians say corruption in the country has worsened “somewhat” or “a lot” during the year preceding the survey, a 17-percentage-point increase compared to 2017. This follows a huge (47-percentage-point) improvement between 2014 and 2017.

- Compared to 2017, there has been a 27-percentage-point drop in popular approval ratings of the government’s performance in fighting corruption – a dramatic reversal of earlier gains. Only a minority (40%) say the government is doing a “fairly” or “very” good job on corruption.

Fighting corruption was one of the main campaign planks of Ghana’s current government. During his inauguration speech in 2017, President Nana Akufo-Addo cited the war on graft as his top priority, pledging to protect the public purse and rejecting the idea that the public service is an avenue for making money (BBC, 2017; Forson, 2017).

Among steps to fight corruption, the government in 2017 created the Office of the Special Prosecutor, designed as a politically independent office to investigate and prosecute certain categories of cases, including allegations of corruption (Finder, 2019). Though launched with high public expectations, the office has been bedeviled by bottlenecks, especially what the special prosecutor has called the “wanton disregard of statutory requests made by the office for information and production of documents to assist in the investigation of corruption and corruption-related offences” (Amidu, 2019). Critics complain that corruption remains pervasive and accuse the government of clearing some its appointees of corruption charges (Asante, 2019; Ghanaweb, 2019).

Ghana ranks 78th out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s (2018) Corruption Perceptions Index, three places down from its 2017 position.

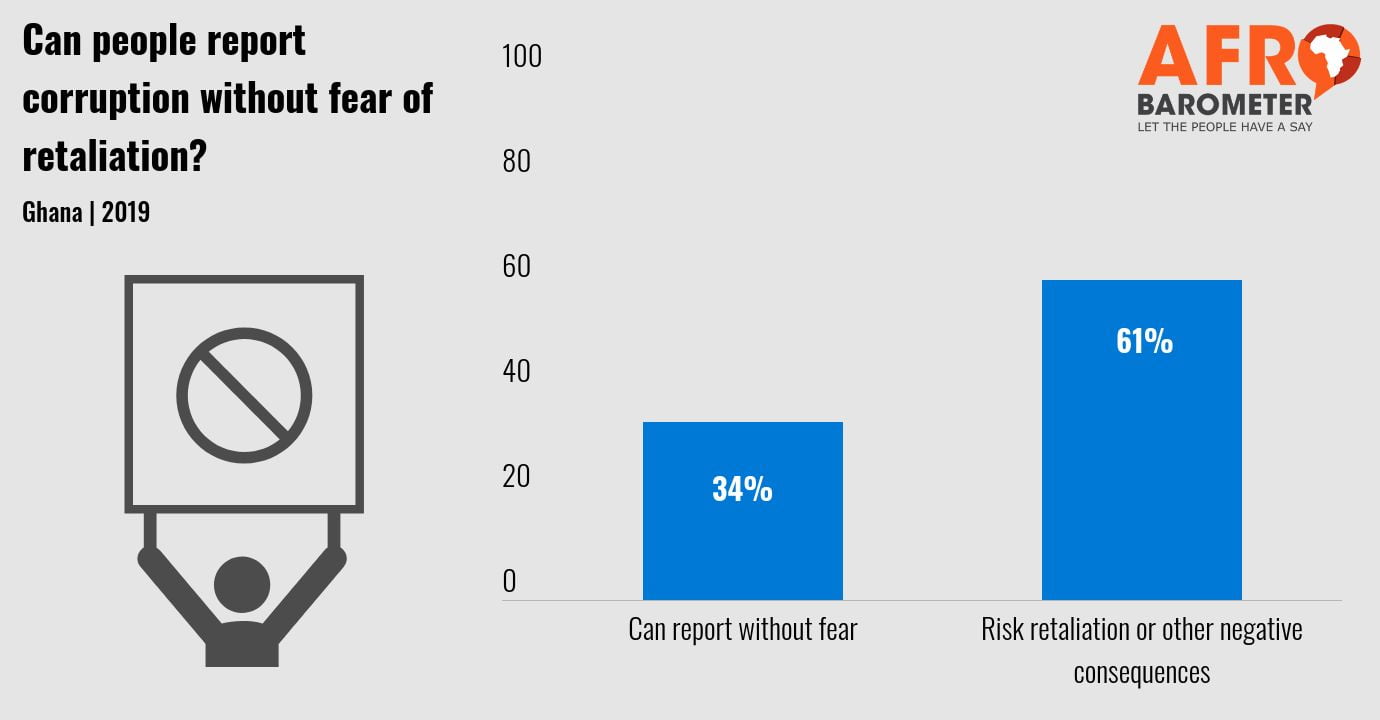

Afrobarometer’s recent survey in Ghana indicates that a majority of Ghanaians say the level of corruption in the country has increased and the government is doing a poor job of fighting it. Most Ghanaians perceive at least “some” corruption in key public institutions, and a majority fear retaliation if they report graft to the authorities.

Related content