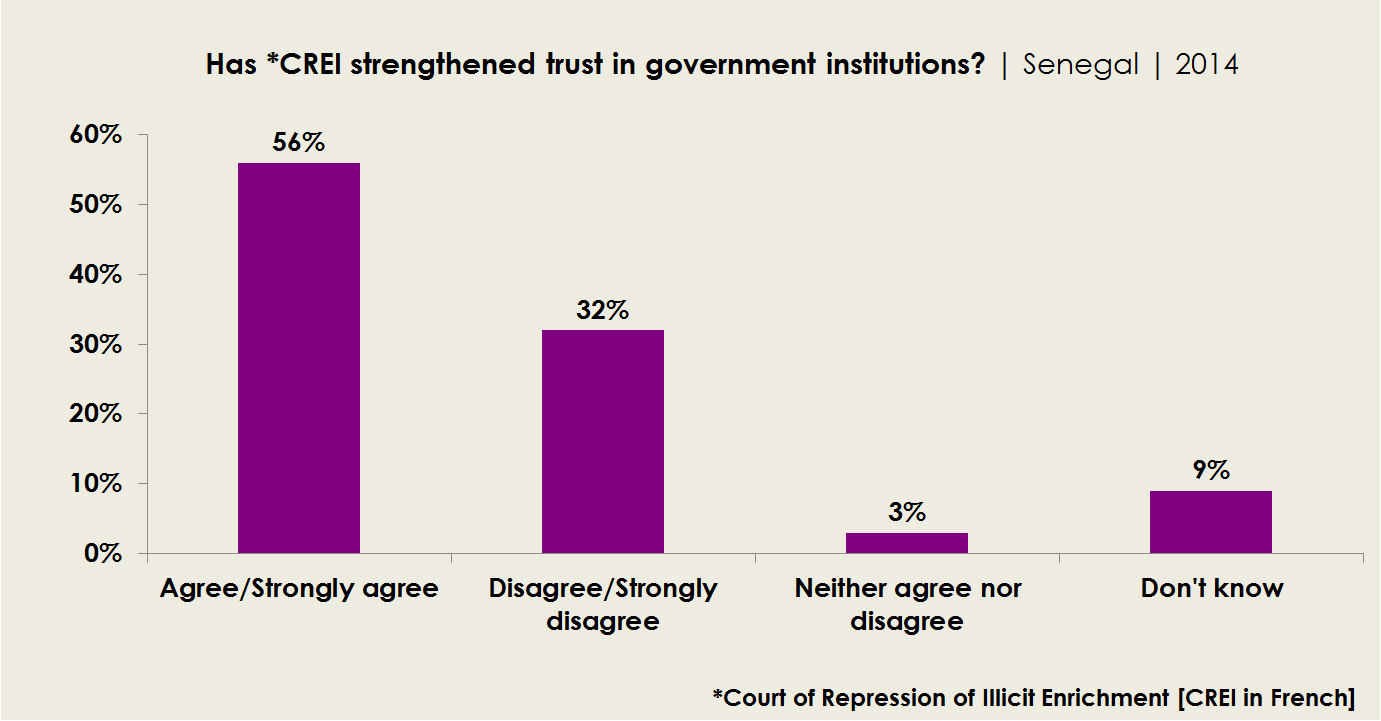

- Slightly more than half (54%) of Senegalese say they have heard about the CREI, while four of 10 (42%) say they are unaware of the court. Male, urban, and bettereducated citizens are far more likely to have heard of the court than their female, rural, and uneducated counterparts.

- Among those who know about the court, more than half (56%) say its work has helped build public trust in government institutions. This perception is particularly common among citizens who trust their elected leaders and see the court system as generally fair.

- Almost half (49%) of respondents who know about the court say that bias in the CREI’s work undermines the credibility of the court and has the effect of increasing the popularity of the accused. This view is especially common among urban residents (52%), respondents with post-secondary education (55%), and those who frequently obtain news from the Internet and social media

- Among respondents who have heard of the CREI, 45% believe that the court’s work has slowed down international investment in Senegalese companies. This concern is more frequently shared by men, the better-educated, the poor, and citizens who offer negative assessments of the country’s economic situation.

The theft of public funds for personal enrichment by elected and autocratic leaders has been a bane of African development (Amadi & Ekekwe, 2014; Ebegbulem, 2012; Owoye & Bissessar, 2012; Gyimah-Brempong, 2002; Bayart, Ellis, & Hibou, 1999; Lawal, 2007). In 1981, Senegal introduced the offense of illicit enrichment into its penal code and created an ad hoc court to deal with such cases of corruption – the Court of Repression of Illicit Enrichment (CREI in French). The court remained dormant until 2012, but a high-profile case in 2014 against Karim Wade, a former Senegalese minister and son of and heir-apparent to former President Abdoulaye Wade, soon drew international attention – and criticism charging political motivations and lack of due process (FIDH, 2014; Reuters, 2015). The International Federation of Human Rights, the African Assembly on Human Rights, the Senegalese League of Human Rights, and the National Organization for Human Rights have claimed that the court does not guarantee a fair trial or presume a defendant’s innocence until proven guilty (Freedom House, 2015). In March 2015, the court announced its verdict in the Wade case: six years’ imprisonment and a fine of US $240 million (Ba, 2015; Reuters, 2015).

In this dispatch, we explore public perceptions of the work of Senegal’s corruption court. Based on responses in Afrobarometer’s 2014 national survey, only a slim majority of Senegalese are aware of the court’s existence. Among those who know about the CREI, most believe that its work has helped strengthen public trust in government institutions. However, many also say that court prejudice undermines its credibility and has the effect of increasing the popularity of the accused. Citizens are split as to whether the CREI’s work has slowed down international investment in Senegalese companies.

Related content