Read the original article here.

A first-time driver on Kenyan roads is likely to think that commercial and passenger service vehicles are highly regulated. Drivers are frequently stopped by police officers, who are ubiquitous along Kenya’s highways.

Is this evidence that the police are keeping road users safe?

Not necessarily. As my research on police corruption at traffic checkpoints and roadblocks in Kenya shows, other factors are at play. One of them is securing bribes.

A number of reports on police corruption in Kenya have been drawn up. However, first-hand data on corrupt transactions at police checkpoints and roadblocks are not easy to come by.

I examined the techniques, rationales and legal gaps that allow for corrupt practices and policing misconduct on Kenyan roads.

My research describes how corruption’s logic, practices and coded languages are developed, how actors are recruited and regulated, the inventing and concealing of evidence, establishment of players or networks, and the forming of norms and normalising of corrupt practices.

I call this process the art of bribery.

My findings into how government institutions work can provide insights into implementing policies that address corruption.

Partners in crime

In Kenya’s traffic stops, bribery is a means to cope and fit within the elaborate network in the police hierarchy. It is an outcome of indoctrination by older timers. There are set rules of the game, some of which are not clearly defined or are loosely regulated.

Motorists pay bribes to circumvent traffic regulations, while the police maximise illicit incomes for personal and institutional gains. Dissidence is rare and may come at a great cost, especially within the police service. But even if dissent occurs in the form of whistleblowing, no significant punishment is meted out on the culprits.

Even though this state of affairs paints a grim image of the police, motorists are equal partners in this corruption racket, especially when they fail to comply with traffic regulations on issues like vehicle loads or speed limits.

Kenya’s unstructured public transport sector and confusing traffic regulations exacerbate bribery at checkpoints, creating a corruption complex that draws in the police and motorists.

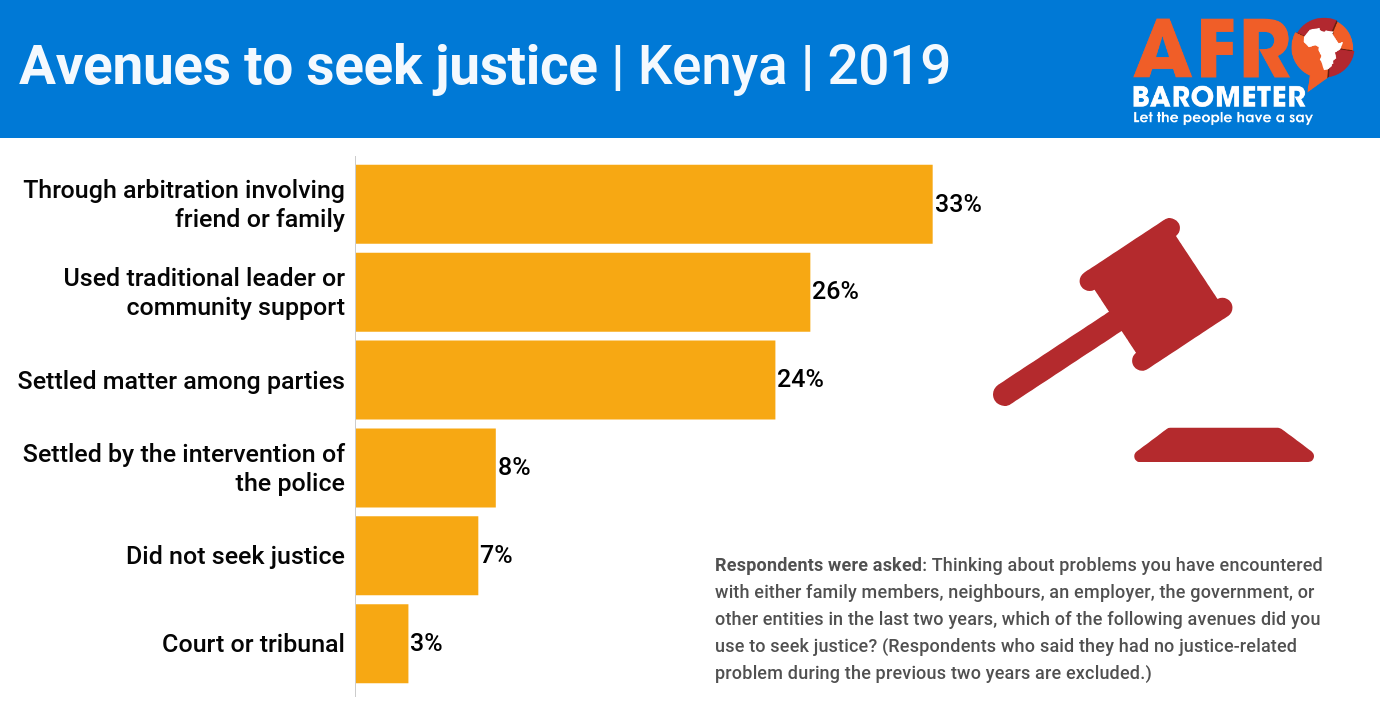

My research was based on an ethnographic study involving police officers and operatives of passenger service vehicles (called matatus) on selected busy routes: Nairobi-Nakuru, Nakuru-Kisumu and Kisumu-Migori. A documentary analysis of secondary data, like Afrobarometer survey findings and statutory and media reports, complemented the primary data.

When asked how bribes are distributed or divided among the police, one police respondent stated: “Hiyo inaenda mbali na hukuliwa na watu wengi, hata wakubwa.” Translated, this means that collected bribes move along the hierarchy to high-ranking beneficiaries at police headquarters.

This suggests that police corruption in Kenya flows within personal and corporate networks that uniquely bring together lower cadre and major players in the police service. These networks are loosely latched onto a well-established and institutionalised culture of corruption.

In interviews, one officer painted a hopeless picture regarding the application of oversight mechanisms in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, when he mentioned that they sometimes ‘eat’ (share bribes) with some Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission officials.

Additionally, seasoned players indoctrinate newcomers. As in most conventional corruption situations, unequal power relations and coercion are the primary drivers.

There are also police officers, mainly base commanders, on retainer payments. Here, owners of vehicle fleets pay bribes in exchange for ‘protection’ or to maintain good relations. The bribery network also involves court officials and magistrates. This turns court corridors into corruption negotiation spaces.

The rules of the game

The rules are clear: don’t involve oversight institutions or lawyers when dealing with the police. Police officers are averse to matatu owners and operatives who think they’re connected and know the law.

The same applies to acts of dissent within the service. The police officers I interviewed mentioned professional witchhunts and victimisation as outcomes of whistleblowing.

For motorists, the legal landscape is too time-consuming and costly to effect their agency against police corruption. Matatu owners reported that their vehicles were targeted or their drivers frustrated after a court process, resulting in a difficult, if not impossible, environment to run a business.

Police recruits are advised or socialised on ‘how things are done here’. In this way, institutional structures and culture reinforce corrupt practices.

When a motorist stopped at a roadblock, a lot could happen. The police officer may decide to impound the vehicle and confine it to a station. This is a route many motorists detest because it shifts the grounds of negotiation in favour of the police.

This is because, first, the police are in custody of the vehicle. Second, it involves a bigger fish, such as a base commander, and the issue could end up in court. Third, one’s offences may change or take a different dimension by the time the case gets to court.

Considering the punitive nature of Kenya’s traffic legislation, many motorists make the choice to bribe at the roadblock.

Essentially, bribery incomes have become a source of livelihood for many police officers. As one police respondent in my research stated:

Ukiangalia vile tunaishi (If you consider how we live), we live in shacks around here. There is no water sometimes and the rooms are suffocating … to make it worse, the salary is not adequate given the Kenya of today. What do you expect me to do?

The way forward

My research found that corrupt exchanges are regulated by the taken-for-granted rules of the game. These legitimise police misconduct, curtail detection and define the scales of bribery.

Likewise, there are socialisation and rationalisation processes among motorists and police officers that lead to non-responsiveness in reporting police misconduct. Furthermore, stricter traffic laws and costly penalties could perpetuate rather than reduce police corruption.

Tackling police corruption, therefore, lies in addressing the broader deficits that hamper the rule of law in Kenya. Corruption is a function of a lack of adequate legislation, and poor quality of police service personnel and public leadership.

The professionalisation of the police should begin by recruiting and attracting highly qualified and educated individuals. This will change the current narrative that portrays the police service as a den of academic underperformers only known for dispensing brute force on the citizenry as in colonial days.

Raising the academic competency of the service will steer it toward becoming an intelligent organisation and transform its image. It will also be able to address current political neglect in the forms of under-remuneration and poor living conditions for police officers.

Finally, professionalising the force will create an enabling environment for the ongoing police reforms, which seek to improve the institution’s effectiveness.

The government must ensure intensive training of the police on the rule of law and citizen rights, conduct public awareness campaigns, and create a less costly and burdensome justice system. This calls for effective collaboration and coordination among state agencies, including oversight agencies and the judiciary.