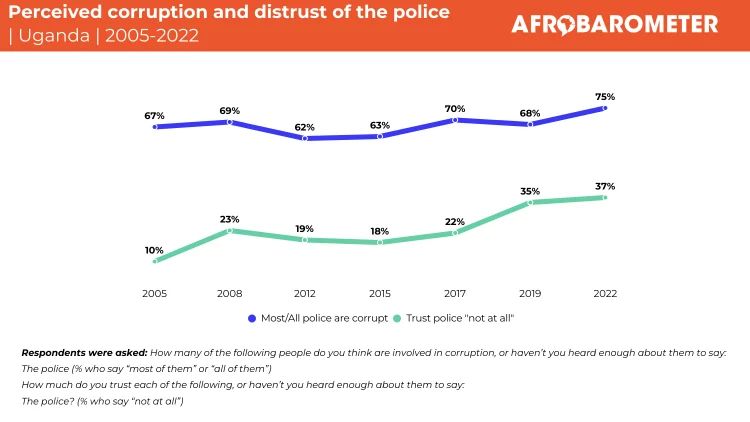

- Trust in the police: Fewer than half (41%) of Ugandans trust the police “somewhat” or “a lot.” The share of citizens who express no trust at all in the police has increased from 10% in 2005 to 37% in 2022.

- Uganda police in comparative perspective: Uganda police are the least trusted among key government institutions in the country and rank among the bottom eight across 34 African countries surveyed by Afrobarometer in Round 8.

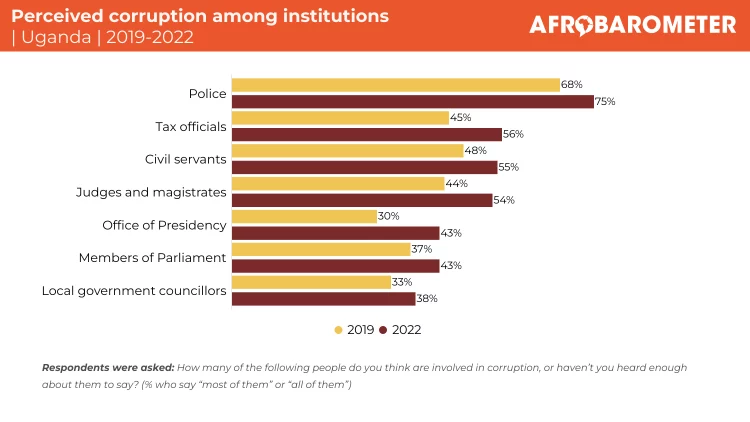

- Police corruption: Three out of four Ugandans (77%) say that “most” or “all” members of the police are corrupt. Uganda police are perceived as the most corrupt among key public institutions and one of the most corrupt police forces in the 34 countries surveyed by Afrobarometer.

- Police professionalism: Only about one in five Ugandans (22%) think the police “often” or “always” operate in a professional manner and respect the rights of all citizens, while 42% say this “never” or “rarely” happens.

- Police brutality: A majority of citizens say the police “often” or “always” use excessive force in managing protests (57%) and in dealing with suspected criminals (54%). Among opposition party supporters, 74% think the police routinely use excessive force with protesters, but even among NRM supporters, half (49%) hold this view.

- Determinants of trust in the police: Statistical analyses show that citizens’ low levels of trust in the police are driven by perceptions of police corruption, brutality, and lack of professionalism and respect for citizens’ rights. Trust in the police is also significantly lower among citizens who support opposition parties and those living in the country’s Central Region (including Kampala).

The police are responsible for enforcing the law, preventing crime, maintaining public order and security, and protecting people’s lives and property. Yet Uganda’s police have often been criticized for brutality meted out against the very citizens meant to be under their protection. Since 2008, more than 100 civilians have reportedly been killed by Ugandan security officers, while many more have suffered injury, harassment, and abuse, often during protests and recently during aggressive enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions (Taylor, 2021; Human Rights Watch, 2011, 2021, 2022; Guardian, 2021; 2022).

Uganda’s national media also continues to report countless cases of repression by the police, particularly against journalists, political activists, and political opponents. Yet accused officers regularly go unpunished; critics contend that laws and provisions regarding the use of force by police officers in Uganda are lax and protect the police (Kiconco, 2018; The Law on Police Use of Force, 2022), and that internal accountability mechanisms such as the police disciplinary courts, regional police courts, and police council have fallen short of their intended objectives (Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, 2006)

Corruption further tarnishes the image of the police. In surveys by Afrobarometer, Transparency International, and others, the Uganda Police Force is consistently ranked as more corrupt than other key institutions (Monitor, 2021; New Vision, 2015; Kakumba, 2021). Civil society groups may see the dismissal in 2021 of 153 officers accused of corruption and inappropriate conduct (Independent, 2021) as a step, but no more than a step.

Some officers’ disregard for the law and excessive use of force have had real consequences on public perceptions of the police. As this policy report demonstrates, over the past two decades, the Uganda Police Force has lost a lot of its most important currency – public trust. Without this trust, it is more difficult for the police to get public support for crime-prevention measures, community safety initiatives, and criminal investigations (Nix, Wolfe, Rojek, & Kaminski, 2015).

A lack of public trust in the police also decreases citizens’ compliance with the law (Jackson et al., 2012; Tyler, 2006). Some analysts even argue that distrust in law enforcement increases the likelihood of the public engaging in mob justice (Kakumba, 2020). Put differently, maintaining public trust in the police is essential not only for enhancing police legitimacy (Hawdon, Ryan, & Griffin, 2003), but also to facilitate the rule of law.

In this policy paper, we make use of multiple rounds of Afrobarometer survey data to answer three related questions about public trust in Uganda’s police. First, how much do Ugandans trust their police force? Second, to what extent does public trust in the police vary over time and among different groups of citizens? Third, what explains the different levels of trust in the police?

We find that as of 2022, fewer than half of Ugandans trust the police, and the proportion who express no trust at all in the police has more than tripled since 2005. Uganda’s police are less trusted than other key governmental institutions in the country, and rank among the least trusted and most corrupt police forces on the continent.

Our analysis also shows that citizens’ perceptions of and experiences with the Uganda police force are very poor. A majority of Ugandans say that most or all members of the police are corrupt and that they frequently use excessive force in dealing with suspected criminals and managing protests. A substantial share of survey respondents report that the police “never” or “rarely” operate in a professional manner or respect citizens’ rights. We demonstrate that opposition party supporters and residents in the country’s Central Region (including Kampala) – an opposition stronghold and the centre of many political protests – are particularly likely to report these negative sentiments.

Based on these findings, we make several recommendations that could go some way toward improving citizens’ perceptions of the police, including revision of the 1994 Police Act, establishment of an independent and external police oversight body, strengthening of parliamentary oversight, and additional training for police officers.