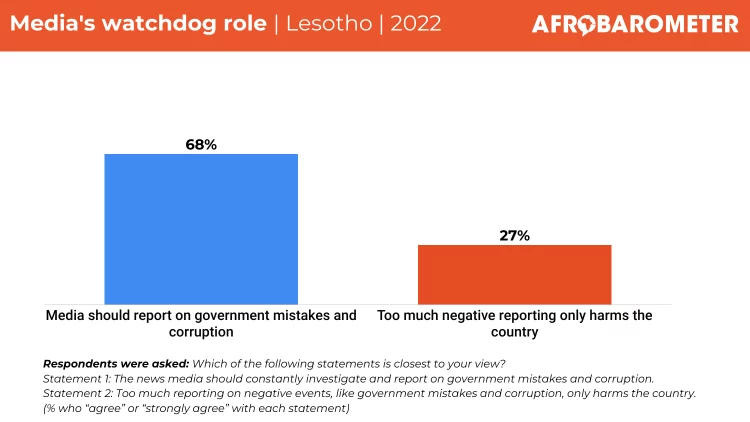

- More than two-thirds (68%) of Basotho say the media should “constantly investigate and report on government mistakes and corruption.”

- About seven in 10 citizens (71%) insist on media freedom, while 27% endorse a government right to prevent the publication of things it disapproves of.

- More than six in 10 (64%) agree with the proposition that information held by public authorities should have to be shared with the public. o In particular, majorities support public access to information regarding budgets and expenditures of local government councils (84%), bids and contracts for government-funded projects or purchases (81%), and the salaries of teachers and local government officials (52%).

- A slim majority (53%) of Basotho say the country’s media is “somewhat free” or “completely free” to report and comment on the news without government interference.

- Radio is the most popular source of news in Lesotho, used at least “a few times a week” by 72% of citizens, followed by television (42%), social media (42%), the Internet (31%), and newspapers (10%).

In May 2023, radio journalist Ralikonelo “Leqhashasha” Joki died in a hail of 14 gunshots after knocking off from his broadcasting job at Ts’enolo FM in Maseru, Lesotho (O’Hagan, 2023; Al Jazeera, 2023; Committee to Protect Journalists, 2023). Joki was famous for exposing five politicians who were illegally trading in alcohol, and his programme Hlokoana la Tsela (“I heard it through the grapevine”) regularly offered commentary on government, corruption, and land-related matters (Civicus Monitor, 2023).

Although media freedom is safeguarded under Lesotho’s constitutional provisions of freedom of expression, critics argue this has done little to protect journalists and media outlets (Media Institute of Southern Africa, 2020; U.S. Department of State, 2022; Southern Defenders, 2023).

While investigations are still ongoing (Lesotho Times, 2023b; Reporter, 2023; United Nations, 2023; Newsday, 2023), many observers believe that Joki, like others in his field who have been harassed and tortured for unmasking shady government dealings (Ntsukunyane, 2021; Lesotho Times, 2023a; Harvest FM, 2023), was a victim of a growing number of violent attacks against journalists. Joki reportedly received multiple death threats on social media before his murder (Cheeseman, 2023; National Press Club, 2023; VOA News, 2023).

For years, media activists in Lesotho have been calling for legislative reforms to establish professional media practices and to promote a more diverse and open media market, steering away from a tendency toward centralised state control (Reporter, 2021). Lesotho has about 30 radio stations, including the national station, Radio Lesotho, and one national television station (Africa Press, 2022; Matšasa, Sithetho, & Wekesa, 2019; BBC, 2023).

In 2021, the government adopted a national media policy that protects the right to access and impart information to all citizens (Media Institute of Southern Africa, 2021; Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa, 2022). This progress opens pathways to give higher priority to the development of complementary legal and constitutional safeguards for media governance in Lesotho (Media Institute of Southern Africa, 2023). In 2023, Lesotho’s media ranked 67th out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index, up 21 places compared to 2022 (Reporters Without Borders, 2023).

What are Basotho’s perceptions and evaluations of their media scene?

According to the most recent Afrobarometer survey, Basotho broadly agree that the media should act as a watchdog over the government, constantly investigating and reporting on government mistakes and corruption.

Citizens value media freedom and reject the notion that public information should be the exclusive preserve of government officials. However, views are mixed on whether media freedom exists in practice.

Radio remains the most popular source of news in Lesotho, with television and social media tied for second place.

Related content