- South Africans see gender-based violence (GBV) as the most important women’s rights issue that the government and society must address.

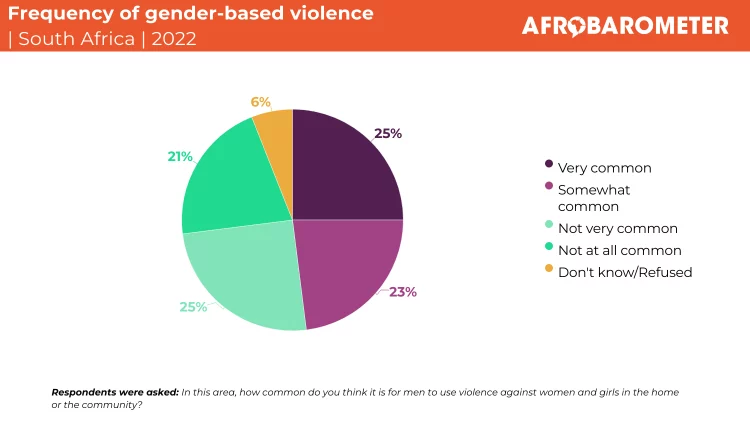

- Nearly half (48%) of citizens say violence against women and girls is a “somewhat common” (23%) or “very common” (25%) occurrence in their community.

- Close to eight in 10 South Africans (78%) say it is “never” justified for a man to use physical force to discipline his wife.

- More than four in 10 respondents (43%) consider it “somewhat likely” (25%) or “very likely” (18%) that a woman will be criticised, harassed, or shamed if she reports GBV to the authorities. o But most (76%) believe that the police are “very likely” (55%) or “somewhat likely” (21%) to take cases of GBV seriously.

- Almost eight in 10 South Africans (78%) say domestic violence should be treated as a criminal matter, while 18% see it as a private matter to be resolved within the family.

South Africa is no stranger to gruesome cases of gender-based violence (GBV). In 2013, 17-year-old Anene Booysen was brutally attacked, raped, and disembowelled in Bredasdorp (September, 2013). In 2017, 22-year-old Karabo Mokoena went missing, and her body was later found burnt in an open field in Johannesburg (Saba, 2017).

In 2019, 19-year-old university student Uyinene Mrwetyana was raped and murdered at a post office in Cape Town (Adebayo, 2019). In 2020, the body of 28-year-old Tshegofatso Pule, who was eight months pregnant, was found stabbed and hanging from a tree outside Johannesburg (Seleka, 2020). A year later, 23-year-old law student Nosicelo Mtebeni was killed and dismembered, her body found stuffed inside a suitcase (Dayimani, 2021). These crimes left the nation reeling, but they are just a few of many.

Releasing second-quarter crime statistics for 2023/2024, Police Minister Bheki Cele reported that South Africa recorded 10,516 rapes, 1,514 cases of attempted murder, and 14,401 assaults against female victims in July, August, and September. In the same period, 881 women were murdered (South African Government, 2023a; Felix, 2023).

During the global coronavirus outbreak, President Cyril Ramaphosa described GBV as a “second pandemic” (CGTN, 2020; Africa Health Organisation, 2021). Reports suggest that GBV intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic as victims were no longer able to escape their attackers (Eyewitness News, 2020).

South Africa’s weapons to fight GBV range from the Constitution, the National Policy Framework for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality, and the National Strategic Plan on Gender-Based Violence and Femicide to support structures such as the Gender Based Violence Command Centre, a 24/7 helpline for victims of GBV (Republic of South Africa, 1996; South African Government, 2002; Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, 2020, 2022).

The Department of Social Development works with civil society and other stakeholders to increase the availability of GBV services and to reduce public tolerance for violence against women and girls (South African Government, 2023b). In 2022, Ramaphosa signed into law three bills designed to deliver justice for victims (South African Government News Agency, 2022), and the South African Police Service has accelerated efforts to assist victims through its Policy on Reducing Barriers to the Reporting of Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence (Philip, 2017; Civilian Secretariat for Police Service, 2017).

As the world marks 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, this dispatch reports on a special survey module included in the Afrobarometer Round 9 (2021/2023) questionnaire to explore Africans’ experiences and perceptions of gender-based violence.

In South Africa, most citizens say physical force is never justified to discipline women, but many report that GBV is a common occurrence in their communities and constitutes the most important women’s-rights issue that the government and society must address. Most consider domestic violence a criminal matter and believe that the police take GBV cases seriously.