- Young Africans (aged 18-35) are more educated than their elders: Almost two-thirds (64%) of youth have had at least some secondary school education, compared to 35% of those aged 56 and older.

- But they are considerably more likely than their elders to be out of work and looking for a job.

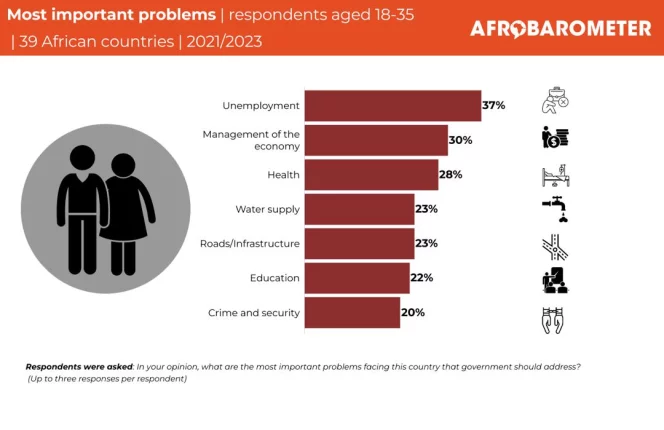

- Unemployment tops the list of the most important problems that African youth want their government to address, followed by management of the economy and health.

- On average across 39 countries, only two in 10 youth (19%) say their government is performing well on job creation.

- Like their elders, young Africans support democracy (64%) and reject such authoritarian alternatives as one-man rule (80%), one-party rule (78%), and military rule (65%).

- However, six in 10 (60%) are dissatisfied with the way democracy works in their country.

- Young Africans are more likely than older cohorts to see state institutions and leaders as corrupt and to mistrust them.

- Youth are also more willing to tolerate a military takeover of the government if elected leaders abuse their power (56% among those aged 18-35 vs. 47% among those aged 56 and above).

- Youth are less likely than older citizens to vote in elections, identify with a political party, attend a community meeting, join others to raise an issue, and contact a local leader.

- Among young people, fewer women than men engage in political processes.

The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the African Union’s Agenda 2063 emphasise the vital role of young people in catalysing sustainable and transformative governance and development in Africa (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2017). Home to a population with a median age of about 19, Africa’s trajectory stands to gain immensely from its youth if their energies and skills are harnessed effectively and they are given the space and opportunity to contribute to public policy and decision making.

For now, young people remain grossly under-represented in formal governance structures as well as political discourse, understood to be an important voting bloc but marginalised from meaningful decision-making processes (Ayaji, Gukurume, & Bangura, 2022). As Niang (2019) observes, Africa has the world’s youngest population and some of its oldest leaders. A combination of legal barriers (e.g. age and financial requirements for public office) and social norms systematically undermines active participation of young people, especially young women, in public policy and development decisions. This disconnect between African political systems – dominated by old men, especially at the highest levels – and African youth results in governance and policy that do not keep pace with the needs and expectations of young people (Ibrahim, 2019).

Critics often cite a lack of interest in politics among young people, particularly when it comes to political parties and voting. However, the explosion of youth participation in unconventional political processes, notably online political and social movements, shows that many are in fact engaged and suggests that their participation may depend on the likelihood that their voices will be heard and will contribute to tangible political change (Van Gyampo & Anyidoho, 2019).

Afrobarometer Round 9 survey results highlight the views and experiences of young Africans as well as some of the challenges they face. Across the continent, unemployment is the top policy priority that 18- to 35-year-olds want their governments to address. Although African youth are more educated than their elders, they are also more likely to be unemployed, and they overwhelmingly give their governments failing marks on job creation. More broadly, compared to older generations, young people are less trustful of government institutions and leaders and more likely to view them as corrupt.

Even so, young Africans are just as committed to democracy and opposed to non democratic alternatives, including military rule, as their elders. But young Africans are particularly dissatisfied with the way democracy works in their countries, and in the event that elected leaders abuse their power, younger Africans are more likely than their elders to countenance military intervention.

As for political engagement, African youth are less involved than older cohorts in conventional processes such as voting, identifying with a political party, and attending community meetings, but are more likely to participate in demonstrations or protests.