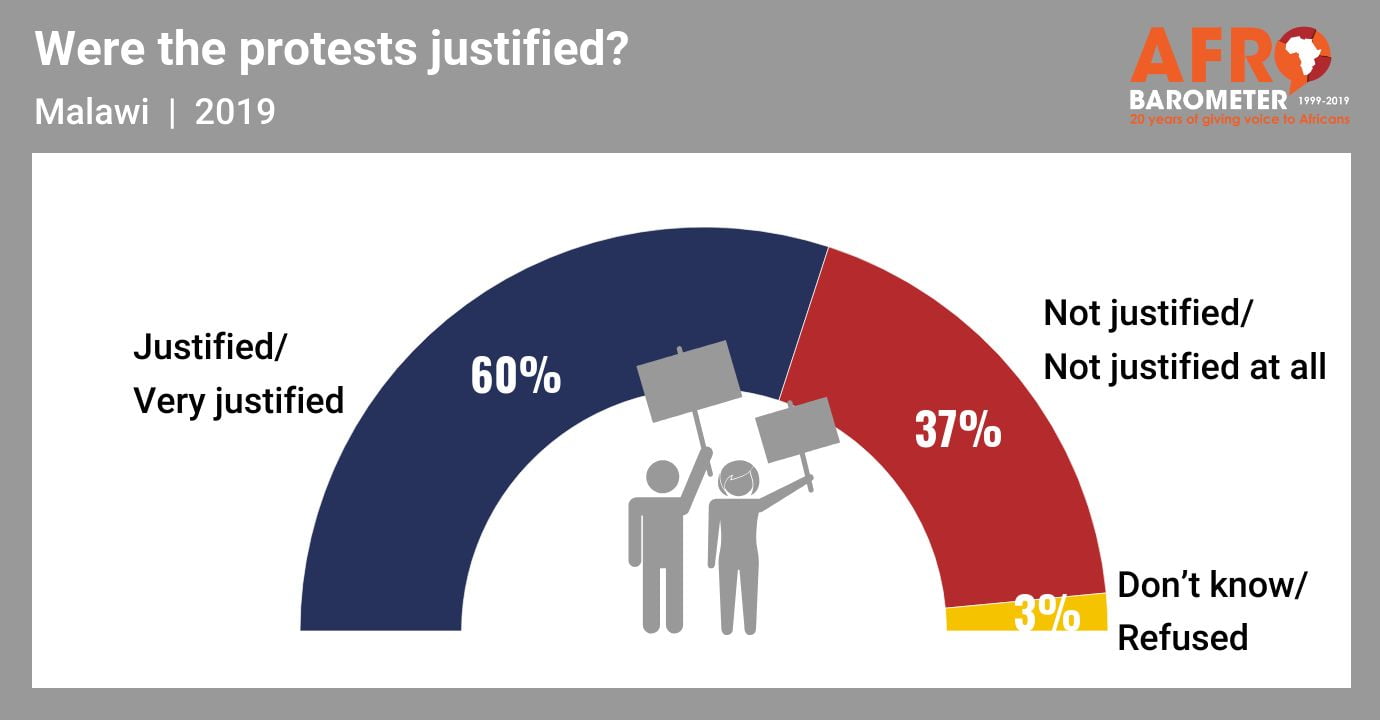

- Of the 77% of Malawians who were aware of the post-election demonstrations as of late 2019, six out of 10 (60%) said the protests were justified.

- ▪ More than half (53%) of Malawians said they agreed with the key demand of protest leaders that the chairperson of the Malawi Electoral Commission resign for mismanaging the election.

- Despite popular support for the post-election protests, fewer than half (45%) of respondents claimed an absolute freedom to demonstrate. A slim majority (51%) instead said the government should have the power to limit demonstrations to protect public peace and security. Political partisanship produced only modest differences on this issue.

- Compared to 2017, the proportion of people who had experienced violence at protests or political rallies during the previous two years doubled, to 16%. Violence was more frequently reported by supporters of the political opposition.

The Constitution of the Republic of Malawi (1995) stipulates that “every person shall have the right to assemble and demonstrate with others peacefully and unarmed.” In the aftermath of the 2019 general election, the country has been engulfed in a series of protest marches. Led by the Human Rights Defenders Coalition (HRDC) of civil society organizations, the protesters continue to demand the resignation of Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) members on charges that they mismanaged the election (Chauluka, 2019). Some protests have degenerated into deadly and destructive clashes with the police and ruling-party cadres (Khamula, 2019; Malekezo, 2019).

In response, President Peter Mutharika and his Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) have labeled protest organizers “terrorist groups” (Maravipost, 2020) and accused them of advancing a regime-change agenda orchestrated by opposition political parties (Chiuta, 2019). The government has repeatedly tried to stop the demonstrations through court orders, by denying protesters “permission” through local government councils mandated to process notification of such assemblies, by demanding huge sums of money for surety, and by prohibiting access to certain areas under the 1960 Protected Places and Areas Act.

These events have ignited debate regarding freedom of assembly in Malawi. Critics say the government is bent on stifling people’s right to protest and recall the 2011 tragedy when at least 20 protesters were shot dead by the police (Mkwanda, 2019). The government contends that protests should be stopped because they are destructive and a threat to public security.

The latest Afrobarometer survey in Malawi shows that as of late 2019, a majority of citizens saw the 2019 post-election protests as justified and agreed with protesters’ demand that MEC Chairperson Justice Jane Ansah resign. However, they were split on whether freedom to demonstrate should be absolute or government should have the power to limit protests to safeguard public security. The proportion of Malawians who had feared and experienced violence during political events and protests showed an increase.

These results point to Malawians’ aspirations for high-quality elections and a desire for a political settlement that will safeguard peace and security without trading off freedoms. This entails restoring the legitimacy of the electoral management body and exploring ways to ensure violence-free protests.