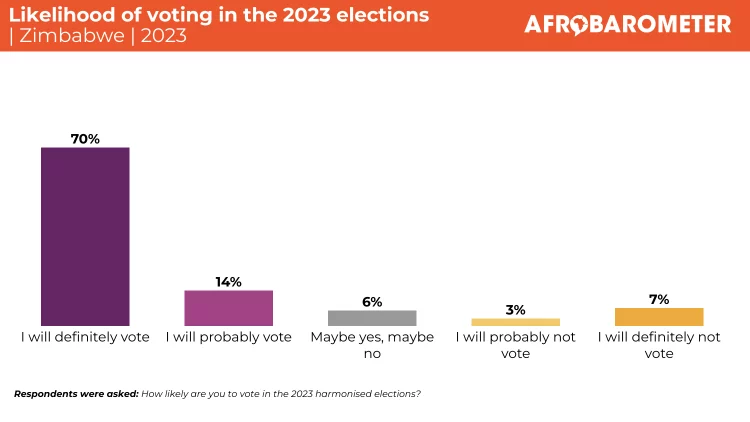

- As of early July 2018, Zimbabweans were ready for elections: 86% of eligible voters (and 97% of registered voters) said they were “probably” or “definitely” going to vote

- At this time, Zimbabweans saw a somewhat more open political atmosphere than for previous campaigns. Fears of free expression and electoral violence had declined slightly, though both remained high (76% and 43%, respectively).

- More people reported attending ruling-party election rallies than opposition-party rallies, especially in rural areas. But more people, especially in urban areas, thought that the opposition’s presidential candidate would perform better at “creating jobs for the people.”

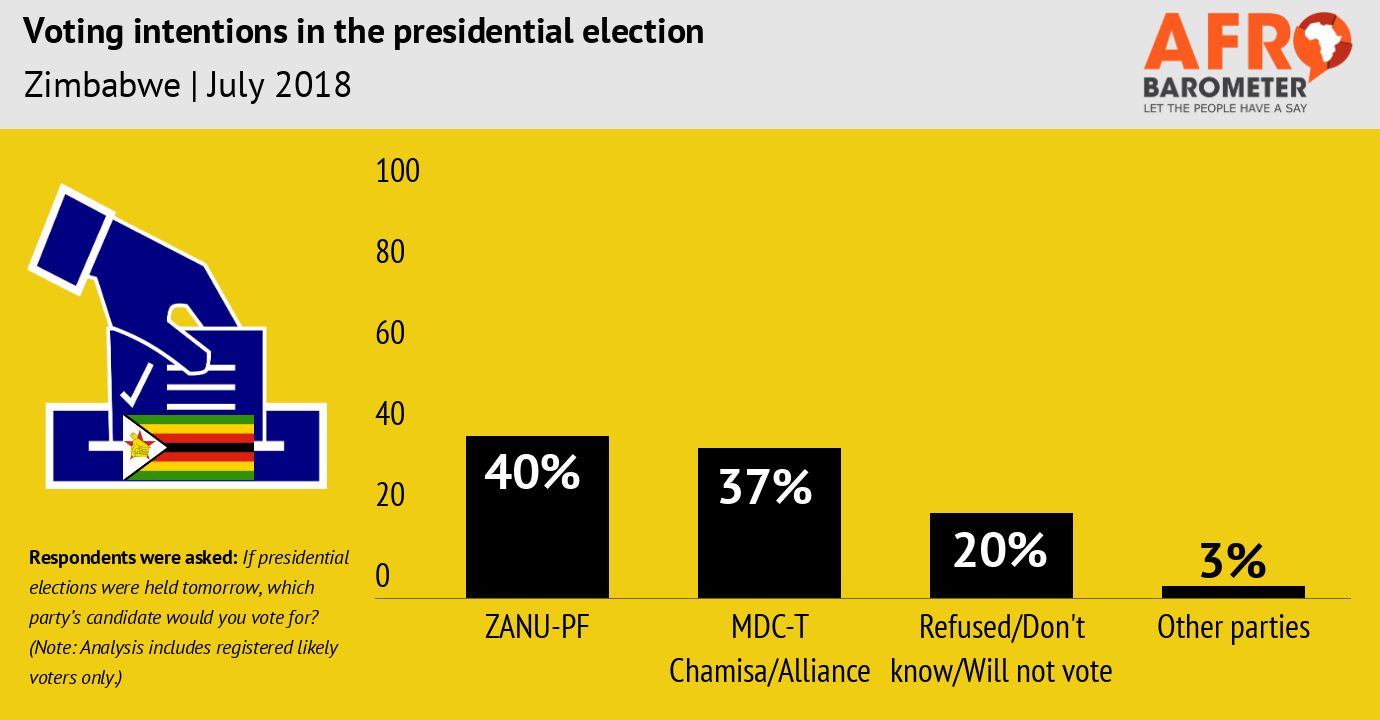

- Compared to the early May survey, by early July the race for the presidency had tightened. Among citizens who were both registered to vote and likely to vote, 40% said they would vote for the ZANU-PF and 37% said they would vote for the MDC (combined party and Alliance).

- Depending on how undeclared voters (20%) ultimately decide to vote, either party had a chance to win the presidential election on the first round

For the first time in a generation, Zimbabweans will vote in presidential, parliamentary, and local government elections on July 30, 2018 without the name of Robert Mugabe at the top of the ballot. Instead, the race for the presidency – the top prize in Zimbabwean politics – will pit Mugabe’s long-time collaborator, Emmerson Mnangagwa of the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), against newcomer Nelson Chamisa, who, with the death of Morgan Tsvangirai in February 2018, inherited the leadership of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC-T Chamisa and MDC Alliance).

At least on the surface, the 2018 election is unfolding in a somewhat more open political atmosphere than the country’s previous contests, which were often marred by violent intimidation and disputed results. The opposition has been permitted to campaign throughout the country, and access to the election proceedings has been granted to a wide spectrum of international observers. But undercurrents of concern remain about the independence of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission, the illicit distribution of public largesse by the ruling party, and the unknown intentions of the security forces, which in the past have repeatedly shored up ZANU-PF against any loss of political power.

Against this backdrop, Zimbabwean voters wonder whether 2018 will break the mold of past elections by ushering in the country’s first-ever alternation of presidential leadership. Certainly the electorate longs for a leader who can bring an end to four decades of economic mismanagement and rising poverty. In response, both Mnangagwa and Chamisa are campaigning on messages of economic reform and job creation. But a skeptical citizenry has every reason to question the sincerity and feasibility of politicians’ easy promises and, in the absence of unbiased information from a polarized and partisan press, to wonder which political party is actually ahead in the quest to occupy the top offices of state.

This dispatch reports results from a survey of public opinion on the status of the electoral race conducted one month before the day of voting with a representative sample of 2,400 voting-age adults drawn from all 10 provinces of Zimbabwe. The survey was commissioned by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, Afrobarometer’s core partner in Southern Africa, and implemented by the Mass Public Opinion Institute, Afrobarometer’s national partner in Zimbabwe.

Related content