First published in the Namibian and the Namibian Sun.

The struggle against the criminalisation of homosexuality is at least 500 years old. In the ongoing case of Dausab vs the Minister of Justice, the Namibian High Court has to decide whether or not the laws that criminalise sodomy among men are unconstitutional or not.

This is but one of several cases over the past decade that challenged the constitutionality of the criminalisation of homosexuality in Namibia.

In this specific case, the state through its legal representative, the attorney general (AG), indicated that it will defend the constitutionality of laws that criminalise sodomy and ultimately prevent the normalisation of homosexuality in Namibia.

Seeing that the Law Reform and Development Commission, in its Report on the Abolishment of the Common Law Offences of Sodomy and Unnatural Sexual Offences, already in November of 2020 recommended that these laws are obsolete and should be abolished, why is the AG so adamant that they should be defended?

The state’s defence is grounded in the view that sexual acts such as sodomy are unnatural, abnormal, unusual, and therefore offensive to the morality of Namibian society. In this line of argument, for example, the state sees no difference between sodomy, on the one hand, and incest and bestiality on the other. Under the law these sexual acts are all unnatural and equally immoral and repulsive.

The AG also argues that “the real question is whether ‘public mores’ have shifted to such a point that the law must find that such laws offend the societal mores. The answer, with respect, is no (emphasis added). The majority of Namibians today do not believe that such laws are obsolete or contrary to public policy.” Protecting the social mores, for him, “is a rational and legitimate governmental purpose. … The purpose of the law is to uphold society’s concept of dignity: There are certain forms of conduct so morally unacceptable that anyone who engages in them undermines their own dignity and the dignity of society. So, in this case, if there is anything which undermines the dignity of homosexuals, it is that they choose to engage in conduct that is frowned upon by society.”

In short, then, the Attorney General claims that the state acts in the interests of the Namibian nation when it defends the criminalisation of sodomy, and that his recommended action is in congruence with public opinion on this matter.

His gauge of public opinion is the elected bodies of Parliament, and since these bodies have not made efforts to repeal the relevant legislation, his conclusion is that public opinion has not shifted enough to warrant changes.

This begs the question: Is he, and the state for that matter, using public opinion and “public mores” to mask the continued oppression of a socio-political minority? Is this an attempt at concealing repression under a cloak of benevolence?

This is very reminiscent of the dark apartheid days, when those in power used those very terms to justify laws that criminalised sexual relations and marriages between people of different races, for example. Have we made no progress since then?

One concept that could help us reflect on Namibian public opinion toward the issue of decriminalising homosexuality and all aspects related to that is “toleration,” also known as “tolerance.” Toleration, which the Encyclopaedia Britannica defines as “a refusal to impose punitive sanctions for dissent from prevailing norms or policies or a deliberate choice not to interfere with behaviour of which one disapproves,” is crucial for addressing the problem of socio-political and cultural diversity and thus the functioning of any liberal democracy. Toleration requires no approval, or agreement, or similarity. It accepts diversity and presents a means to deal with it, even if it means only doing nothing (vindictive) about it.

Round 8 of the Afrobarometer survey, conducted in 34 African countries in 2019-2021, asked a battery of frequently used toleration questions that probe public feelings about having possible members of unpopular or disliked groups such as homosexuals, supporters of different political parties, members of different ethnic and religious groups, and immigrants or foreign workers, as immediate neighbours. Respondents could answer that they would “strongly dislike it,” “somewhat dislike,” “not care about it,” “somewhat like it,” or “strongly like it.” The toleration level is determined by combining the last three response options.

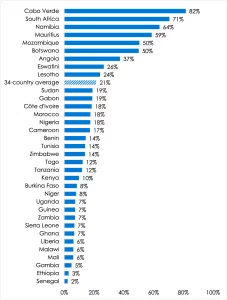

On this scale, Namibia (64%) was the third-most-tolerant of homosexuality on the continent behind Cabo Verde (82%) and South Africa (71%). Namibia ranked 43 percentage points above the African average of 21%. Fellow SADC states Mauritius (59%), Mozambique (51%), Botswana (50%), and Angola (37%) also ranked among the most tolerant. Of the seven most tolerant countries, only Namibia and Mauritius still have laws that criminalise homosexuality. Even Ivory Coast, where only 19% of citizens expressed toleration of homosexuality, has abolished anti-gay laws.

Tolerance of people in same-sex relationships | 34 African countries | 2019/2021

Respondents were asked: For each of the following types of people, please tell me whether you would like having people from this group as neighbours, dislike it, or not care: Homosexuals?

Source: Afrobarometer Round 8 (2019/2021)

The Afrobarometer data show that there is significant variance in tolerance of homosexuality across the 34 African countries. This refutes the often-used notion that Africa is uniform in its intolerance of homosexuality.

The data also show that toleration in Namibia is consistent. Those who are tolerant of homosexuality are also tolerant of ethnic, religious, and political diversity, and show little sign of being xenophobic. This degree of toleration may well contribute to the political stability Namibia has enjoyed since independence.

The African data suggest that there may well be a direct positive correlation between the degree of tolerance of homosexuality and legislative and policy reform to decriminalise homosexuality. Namibia is an outlier to this pattern. The question is why? Who is blocking reform? The people, or those in positions of power?

Ultimately, what needs to be overcome is not homosexuality but the repression that impedes living homosexuality. In a democracy, it is the state’s job to protect socio-political minorities, not repress them.

Christie Keulder is the owner of Survey Warehouse, Afrobarometer’s national partner in Namibia. Opinions expressed are his own. Email: c.keulder@surveywarehouse.com.na.