By Carolyn Logan and E. Gyimah-Boadi

Carolyn Logan is director of analysis for Afrobarometer (@afrobarometer) and associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Michigan State University. Find her on Twitter @carolynjlogan.

E. Gyimah-Boadi is interim CEO of Afrobarometer. Find him on Twitter @gyimahboadi.

Originally published on the Monkey Cage blog.

While the COVID-19 toll thus far in Africa has been less severe than many analysts initially feared (South Africa being the major exception), the Gates Foundation and others have warned that the pandemic may wipe out years of progress toward fighting poverty and improving health around the world.

These setbacks are likely to increase pressures on African governments. Even before the pandemic, citizens were already demanding urgent action on jobs and health, and growing increasingly critical of their countries’ overall direction, Afrobarometer public attitude surveys show.

The new bi-weekly Friday Afrobarometer series, starting today in TMC at the Washington Post, will explore these and other critical current topics, helping to explain Africans’ democratic aspirations and economic ambitions that will mark policy engagement with Africa well beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Let’s dive right in.

Many Africans feel their country is headed in the wrong direction

Across 18 African countries surveyed in 2019-2020, citizens were becoming increasingly negative about the direction things were going in their countries. Less than a decade ago, much popular discourse touted the “Africa rising” narrative of a youthful, democratizing, tech-savvy continent destined for sustained economic growth.

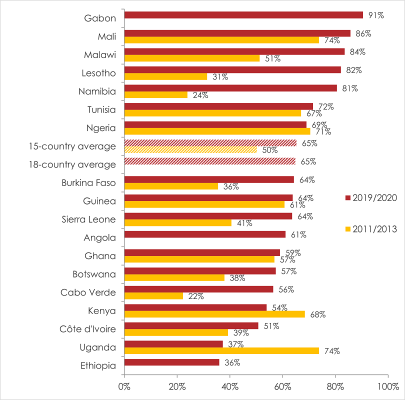

Yet in the recent surveys, about two-thirds (65%) said their country is going in the wrong direction. Across 15 countries where Afrobarometer has asked these questions since 2011-2013, perceptions have deteriorated sharply over time: Average disapproval climbed from 50% to 65% (Figure 1), including double-digit percentage-point increases in nine countries.

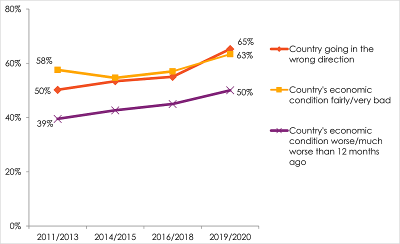

The patterns are similar for purely economic indicators. Across 18 countries, 63% described their country’s economic conditions as “fairly bad” or “very bad,” while just 24% gave a positive assessment. A majority also said their country’s economic condition had deteriorated over the previous year (52%). All of these assessments have worsened substantially since the 2011-2013 survey (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Country going in the wrong direction | 18 countries | 2014-2020

Respondents were asked: Would you say that the country is going in the wrong direction or going in the right direction? (% who said “wrong direction”)

Figure 2: Increasingly negative perceptions of country direction and economic conditions | 15 countries | 2011-2020

Respondents were asked:

Would you say that the country is going in the wrong direction or going in the right direction? (% who said “wrong direction”)

In general, how would you describe the present economic condition of this country?

Looking back, how do you rate economic conditions in this country compared to 12 months ago?

Despite these increasingly pessimistic assessments, Africans, on average, remained modestly optimistic about the future. Across 18 countries, a plurality (49%) expected economic conditions to get better in the next year, although optimism, too, declined, from 60% across 15 countries in 2011-2013 to 50% in the recent surveys.

Africans demand answers

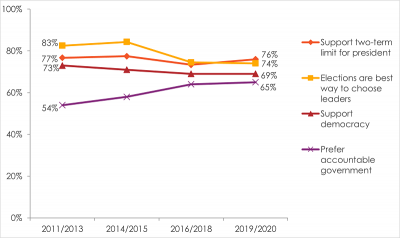

Even if their assessments have grown grimmer, or their expectations greater, Africans continue to look to democracy and accountable governance for answers. Across 18 countries, more than two-thirds (68%) of respondents expressed a preference for democracy over any other political system, a preference that has remained fairly steady since 2011 (Figure 3). Even larger proportions reject presidential dictatorship (81%), one-party rule (76%) and military rule (73%).

Figure 3: Support for democracy and democratic institutions | 15 countries | 2011-2020

Respondents were asked:

Which of these three statements is closest to your own opinion?

Statement 1: Democracy is preferable to any other kind of government.

Statement 2: In some circumstances, a non-democratic government can be preferable.

Statement 3: For someone like me, it doesn’t matter what kind of government we have.

(% who say democracy is preferable to any other kind of government)

Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: We should choose our leaders in this country through regular, open, and honest elections.

Statement 2: Since elections sometimes produce bad results, we should adopt other methods for choosing this country’s leaders.

(% who “agree” or “agree very strongly” with Statement 1)

Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: It is more important to have a government that can get things done, even if we have no influence over what it does.

Statement 2: It is more important for citizens to be able to hold government accountable, even if that means it makes decisions more slowly.

(% who “agree” or “agree very strongly” with Statement 2)

Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: The Constitution should limit the president to serving a maximum of two terms in office.

Statement 2: There should be no constitutional limit on how long the president can serve.

(% who “agree” or “agree very strongly” with Statement 1)

A large — though declining — majority consider the ballot box the only legitimate method of selecting leaders, and support for presidential term limits is strong and steady.

Africans also increasingly insist on the importance of accountability: Across 15 countries tracked since 2011, preference for having an accountable government over one that “can get things done” has increased by more than 10 percentage points, from 54% to 65%. In other words, dictators are not welcome, even if they claim to offer effective governance.

What do Africans see as the top priorities?

When Afrobarometer asked respondents to identify up to three “most important problems that government should address,” at the top of the list were jobs (mentioned by 35% of all respondents) and health care (32%). The longer-term economic and societal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to reinforce these priorities. But the pandemic also highlights other issues that are central to the well-being of individuals and society, from media freedom and trustworthiness to the inter-connectedness and inter-dependence of people and countries.

Afrobarometer, whose face-to-face surveys have been taking the pulse of African publics in as many as 38 countries since 1999, will explore many of these issues in the coming weeks, starting with a look at perceptions of the police that help explain Nigeria’s massive demonstrations for police reform.

The series will continue every two weeks, on topics including:

- China vs. the United States —In their competition for influence in Africa, who’s winning? Do Africans see U.S. and Chinese engagement as beneficial or detrimental to their interests? Which global power is gaining popular appeal as a development model? Is it time to start introducing Chinese language instruction into African classrooms?

- Media — Do Africans support media freedom? How reliable do they believe their news sources are? Has the concept of “fake news” gained traction — or instilled worry— among news consumers? Do ordinary Africans think social media plays a positive or negative role in their news landscape?

- Social cohesion — How strong are the social bonds — or how deep are the divisions — among Africans of different economic status or religious or ethnic backgrounds? Are the ties of national identity stronger or weaker than the bonds of other identity groups?

- Globalism — How national or international is the outlook of ordinary Africans? Should countries open their borders to corporations and products from other countries or regions, or should governments protect local producers and traders? And are citizens more inclined toward local taxes and self-reliance, or loans and global interdependence, in building their economies?

- Populism — Are Africans ready to jump on the populist bandwagon that has been gaining a foothold in other parts of the world, or do they continue to put their faith in institutions, experts and the rule of law to advance the interest of ordinary citizens?

In addition, as Afrobarometer gradually resumes fieldwork interrupted by the coronavirus, and gathers new post-COVID-19 data, we will begin to explore the effects of the pandemic on people’s lives and livelihoods, and their perspectives on how effectively — or not — their governments responded to the crisis.

We hope you will join us.

Image: Borana Women, Southern Ethiopia, Photographer: Rod Waddington, CC BY-SA 2.0 Original available here: https://bit.ly/3miQSFp