The August 2016 local government elections in South Africa sent an earthquake through the political class when the African National Congress (ANC) lost power in three major cities of the country. Coalition governments led by the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) took over the economic powerhouse, Johannesburg; the administrative capital and seat of the Presidency, Pretoria; and the biggest city in the Eastern Cape and the country’s vehicle-manufacturing hub, Nelson Mandela Bay. Additionally, the DA grew its share of the vote to more than two-thirds in Cape Town, the home of Parliament. In Ekurhuleni and other cities, the ANC created coalitions and barely clung to power.

These elections can be seen as a milestone, indicating for the first time since 1994 that the ANC could lose power anywhere in the country. They also point to continuing perceptions of political and systemic weaknesses – including a lack of qualified staff, capacity, professionalism, and accountability (Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2009) – at the local level of government, which deals most directly with citizens, is the coalface of service delivery, and thus may be most directly affected by public dissatisfaction with public services (Mungai, 2015; Institute for Security Studies, 2009).

Since 1994, South Africa’s democratic governments have extended basic service provision to poorer areas of many cities, towns, and rural areas. For the first time, many citizens have enjoyed electricity and sewage systems that had previously been reserved for whites-only suburbs.

According to the 2016 Statistics South Africa General Household Survey, electricity mains now reach 84% of the population. Water access is at 88%; 81% have access to improved sanitation; and only 4% are without a toilet facility. About two-thirds (65%) have their refuse removed once a week, compared to half or less before 1994 (Statistics South Africa, 2017).

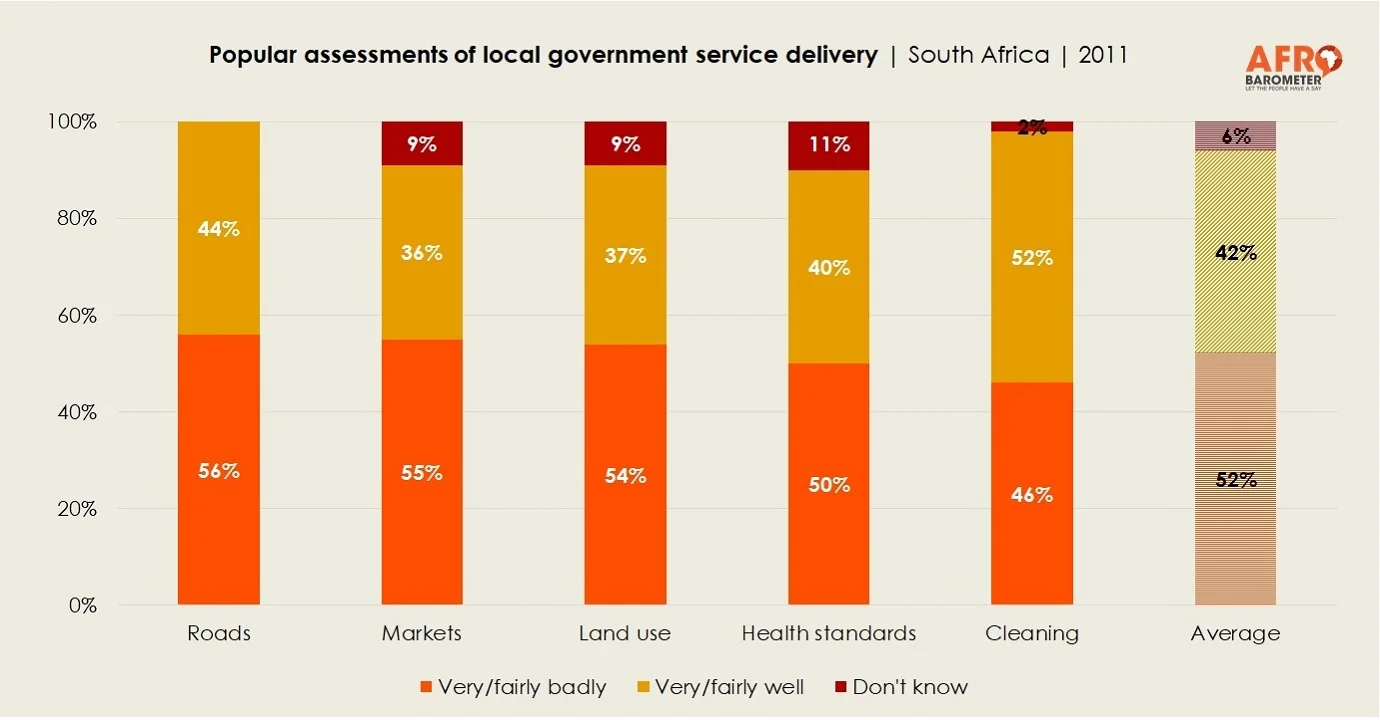

Nonetheless, numerous demonstrations and protests, often violent, have highlighted popular perceptions that local governments have not kept campaign promises of good service delivery – most fundamentally, Nelson Mandela’s 1994 promise of “a better life for all.” Although services may be reaching people who never had them, is the quality of services inadequate to satisfy their recipients? Do service-delivery deficits reflect and perpetuate the apartheid-era spatial design of most towns, retarding racial and class integration and equality?

This paper explores public opinion on basic services provision at the local government level in South Africa. Building on Bratton (2012), which focused on local councillors’ responsiveness to constituents’ needs, I explore other factors that may influence public perceptions of local service delivery, including contact with local councillors and councillors’ job performance and trustworthiness. I also examine which actions, if any, citizens take when they see problems in their municipality.

Related content