- On average across 39 countries, a majority (55%) of Africans reject the proposition that information held by public officials and agencies is exclusively for government use and should not have to be shared with the public. o Popular demand for access to information held by public officials exceeds three fourths of citizens in Botswana (79%) and Madagascar (76%) but drops as low as 38% in Mauritania.

- Specifically, about eight in 10 respondents say information about local government budgets (81%) and local government bids and contracts (78%) should be accessible to the public. A slimmer majority (55%) favour public access to information about the salaries of local government officials and teachers.

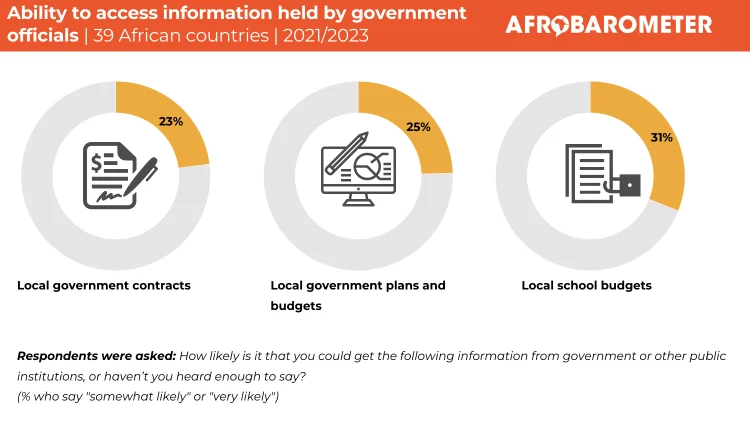

- However, most Africans believe access to this information is restricted. More than seven in 10 respondents consider it unlikely that they could obtain information about local government bids and contracts (72%) and local government budgets (71%), and 65% hold the same view regarding local school budgets. o With just two exceptions, no surveyed country records a majority who think they could access any of these types of information. The exceptions are Niger and Zimbabwe, where 52% and 51%, respectively, believe citizens could obtain information about local school budgets.

- Access to information is strongly associated with perceptions of corruption and trust: Citizens who consider it unlikely that they could access local government and school information are more likely to perceive widespread corruption among government officials at all levels, including the Presidency. And trust in local government officials and members of Parliament is much lower in countries where citizens feel they cannot access information about their local governments and schools.

“GRA-SML contract: Finance Ministry denies Manasseh’s RTI request.” This headline on a story about investigative journalists denied access to a contract between the revenue authority and a private company (Modern Ghana, 2024) is all-too-common news on the continent, even in countries with right-to-information (RTI) laws. While a growing number of African states have enacted RTI laws – Zambia became the 28th in December (Africa Freedom of Information Centre, 2024) – significant implementation gaps persist.

Asogwa and Ezema (2017) attribute the poor implementation of RTI laws in Africa to “restrictive clauses, lack of understanding of the laws by public officials and citizens, lack of political will and oversight mechanisms and the inability of institutions to comply with access to information law obligations.” In a case study of RTI laws in four African countries, the Africa Freedom of Information Centre (2021) found large inconsistencies in compliance with RTI provisions among public institutions in Nigeria and Zimbabwe and concluded that effective implementation is a function of political goodwill and the capacity and commitment of public institutions.

The right of citizen access to public information has been part of Africa’s continental policy discourse for many decades. Article 9(1) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, adopted in 1981, provides that “every individual shall have the right to receive information” (African Union, 1981). To give effect to this provision, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (2013) adopted a model law to provide a blueprint for access to-information laws and facilitate the work of lawmakers in member states. More recently, the African Union’s (2015) Agenda 2063 (Aspiration 3) and the United Nations’ (2015) Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 16) have included specific objectives on public access to information, giving governments, policy actors, and activists clear markers to measure progress and lending momentum to the right of public access to information agenda.

The push for public access to information at continental and global levels is palpable, evidenced in part by the spread of RTI laws. But what are the experiences of ordinary Africans regarding access to public information? Do they think they have the right to access information held by government authorities? How likely do they think it is that they can access such information if they make a request? We draw on the latest Afrobarometer survey data to explore these questions.

Across 39 countries surveyed in 2021/2023, a majority of Africans express support for public access to information such as local government budgets, local government bids and contracts, and even the salaries of public officials and teachers. But although demand for public information is high, few citizens think they could obtain such information.

While public officials may argue in favour of keeping information secret, the data show that access to information is strongly associated with perceptions of corruption and trust: Citizens are more likely to view their elected leaders as corrupt, and less likely to trust them, in countries where access to information is perceived to be difficult.