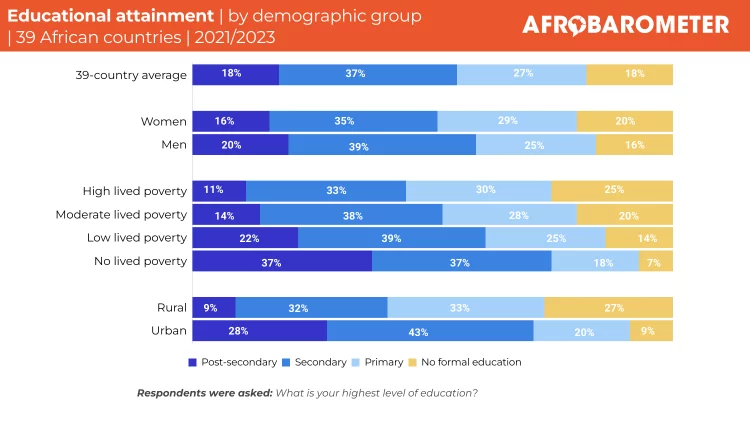

- On average across 39 African countries, more than half (55%) of adults have secondary (37%) or post-secondary (18%) education, while 27% have primary schooling and 18% have no formal education. o Educational attainment varies widely across countries and demographic groups, reflecting disadvantages among women, the poor, and rural residents. Younger Africans have more education than their elders.

- Almost half (48%) of Africans say school-age children who are not in school are a “somewhat frequent” or “very frequent” problem in their community, reaching as high as 83% in Liberia and 71% in Angola.

- Among citizens who had contact with public schools during the previous year, three fourths (74%) say they found it easy to obtain the services they needed. o And three-fourths (74%) say that teachers or other school officials treated them with respect. o But one in five (19%) say they had to pay a bribe to get the needed services, ranging from 2% in Cabo Verde to 50% in Liberia. Poor respondents are twice as likely as well-off citizens to report having to pay a bribe to a teacher or school official.

- Fewer than half (46%) of Africans think their government is performing “fairly well” or “very well” on education, while 52% give their leaders poor marks.

- Education ranks sixth among the most important problems that Africans want their governments to address, but takes the top spot in Liberia and Mauritania.

Sub-Saharan Africa has the world’s highest rates of out-of-school children, including more than one in five 6- to 11-year-olds and almost three in five 15- to 17-year-olds (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2024; UNESCO, 2023).

The pursuit of education, essential for societal progress and individual growth, is a global challenge highlighted by the United Nations’ (2024) Sustainable Development Goal No. 4, which calls on countries to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Despite progress in primary school enrolment (World Bank, 2023), African countries face persistent barriers to achieving that goal, from school fees and too few rural schools to a shortage of qualified teachers (Klapper & Panchamia, 2023; Mayekoo, 2023).

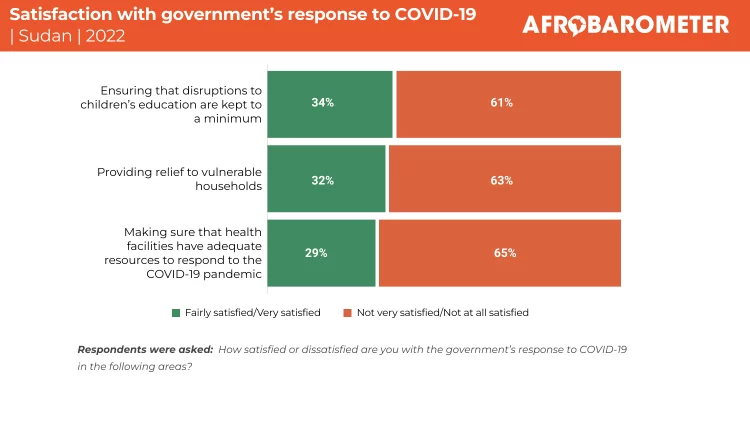

As it did throughout much of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic delivered a major setback for education goals in African countries as children lost months – in some cases years – of instruction (Asim, Gera, & Singhal, 2022; Human Rights Watch, 2020; UNICEF Africa, 2022). Countries in sub-Saharan Africa recorded an average of more than 30 weeks of school closures (United Nations, 2022), raising dropout rates and exacerbating social and gender inequalities (Kidman, Breton, Behrman, & Kohler, 2022; Klapper & Panchamia, 2023; Davids, 2023; Warah, 2022).

Afrobarometer’s Round 9 survey findings from 39 African countries show that while younger citizens have more education than their elders, educational attainment varies widely by country and reflects persistent disadvantages among women, the poor, and rural residents. Many respondents report out-of-school children as a frequent problem in their community.

Among adults who had recent contact with a public school, most say they found it easy to obtain the services they needed and were treated with respect, though a sizeable minority report having to pay bribes.

Overall, fewer than half of Africans are satisfied with their government’s performance on education, which ranks sixth among the most important problem that citizens think need urgent action.

Related content