- Most Gambians express tolerant attitudes toward people of different ethnic (94%), religious (79%), and national (88%) backgrounds. But they are overwhelmingly intolerant (96%) toward homosexuals

- Only about one in 10 Gambians (9%) say they identify more strongly with their ethnic group than with their nation. About half (53%) identify more or only as Gambian, while 36% value both identities equally

- About one in six Gambians (16%) say they experienced discrimination or harassment based on their ethnicity during the previous year, while smaller proportions say they were discriminated against or harassed based on a disability (11%), their gender (8%), or their religion (4%).

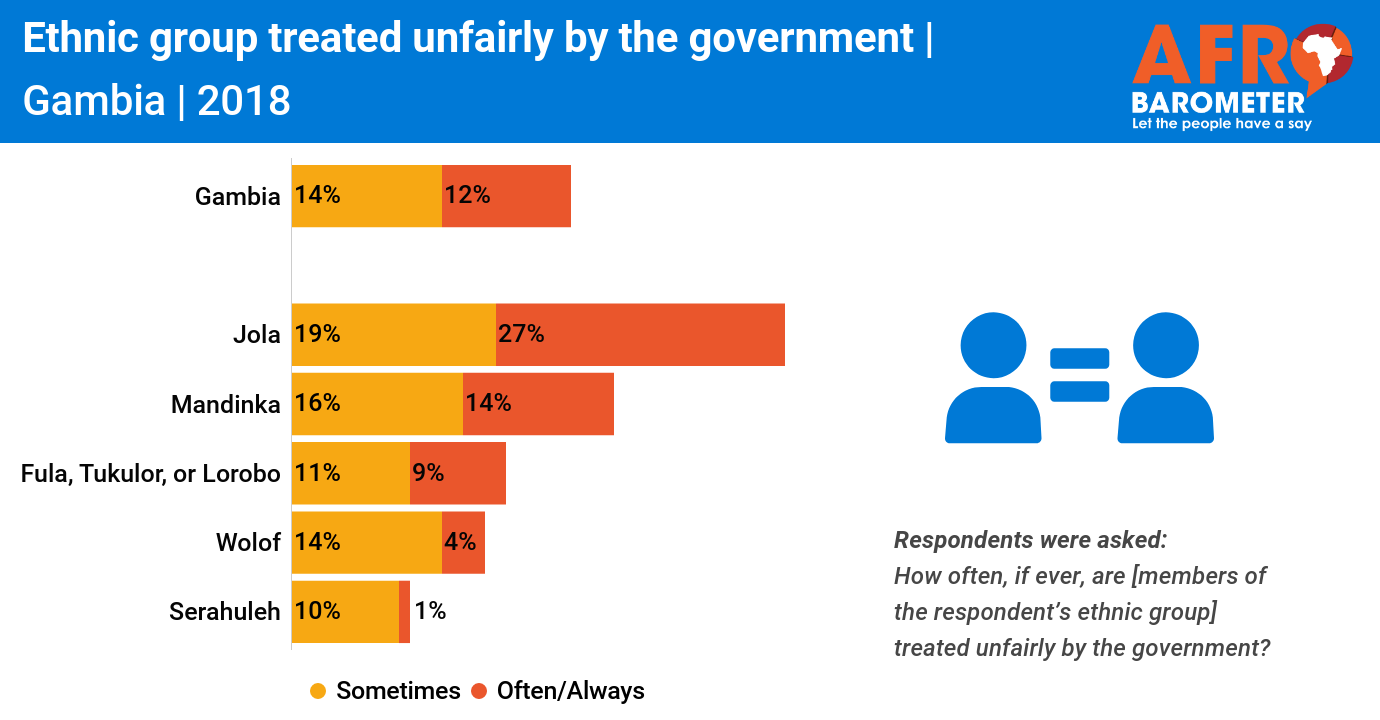

- Among major ethnic groups, Jola respondents are most likely to say that they experienced discrimination or harassment (25%) and that their ethnic group is treated unfairly (46%).

- A strong majority (70%) of Gambians support government by secular law rather than religious law. Support for religious law is stronger among poor citizens (40%) and respondents who say they are “not at all satisfied” with the way democracy is working in the Gambia (40%).

The Gambia does not have a history of ethnic and religious tensions. But starting under former President Yahya Jammeh and continuing since the change of government in 2017, political rivalries are increasingly taking an ethnic form (Courtright, 2018).

The government’s 2018 Conflict and Development Analysis noted a marked erosion of ethnic, regional, and religious relations in the country during Jammeh’s two-decades-long autocratic rule, which was marred by egregious human rights violations (Government of the Gambia, 2018). For instance, in 2015 Jammeh declared the Gambia an Islamic state (Al Jazeera, 2015), and at a political rally in 2016, following protests by opposition United Democratic Party members, he threatened to eliminate the Mandinka, the dominant ethnic group in the Gambia (UN News, 2016). In an address to Parliament, current Vice President Isatou Touray accused Jammeh of having favored his home region, Foni (Africa Press, 2019).

Since assuming office in January 2017, the Adama Barrow government has launched a series of initiatives, including the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission and the Constitutional Review Commission, aimed at redressing past injustices and promoting national reconciliation. While most Gambians welcomed these reform processes, particularly the constitutional review (Isbell & Jaw, 2020), they have been marred by accusations and counter-accusations of exclusion, and members of Parliament close to Barrow recently shot down a new draft Constitution, apparently in an attempt to strengthen Barrow’s re-election chances (Jaw, 2020).

Tellingly, the most controversial debate over the draft Constitution was about whether to describe the Gambian government as “secular.” While the Christian Council preferred the word to be added as a safeguard against having the country declared an Islamic state (Makasuba, 2020), the Supreme Islamic Council and other Muslims argued that adding the word would encourage acceptance of homosexual acts and other practices they oppose.

Given the increasing polarization in the post-Jammeh Gambia, how tolerant are Gambians, and how salient are ethnicity and religion? Afrobarometer survey data from 2018 suggest that most Gambians are tolerant of different ethnicities, religions, and nationalities, though not of different sexual orientations. While majorities did not personally experience discrimination based on ethnicity or religion, substantial proportions say the government treats their ethnic group unfairly. A majority of Gambians also voice support for government under secular rather than religious law.