Afrobarometer has observed for many years that African opposition parties seemed to face some special hurdles in their struggle to win elections and take hold of the reins of power. The number of electoral alternations – whereby a ruling party loses an election and the opposition becomes the new ruling elite – has been increasing in Africa, the most recent example being the All Progressives Congress (APC) win in Nigeria in March. But there are still many countries that hold multiparty elections but have yet to experience such a changing of the guard.

The oppositions’ particular challenges became evident when we first switched (back in Round 3, 2005-2006) from asking generally about “trust in political parties” to distinguishing between trust in the ruling parties and trust in the opposition. A 20-percentage-point trust gap was quickly revealed: While 56% of respondents across 18 countries said they trusted ruling parties “somewhat” or “a lot,” only 36% said the same about opposition parties. Opposition parties were in fact the least trusted institution among 13 that AB asked about (see Working Paper 94).

Why do African voters hold opposition parties in such low esteem? Does it arise from a cultural deference to leaders or preferences for consensus-based politics (as I argued in an earlier analysis of that Round 3 data)? Or are Africans simply risk-averse, reluctant to give never-tested opposition parties a chance (better the devil you know…)? Or have weak slates of candidates and/or poor access to media inhibited the ability of opposition candidates and parties to even generate name recognition, much less sell themselves as a viable alternative (see Working Paper 135)?

The plot thickened when Afrobarometer started asking in Round 4 (2008-2009) about the proper role of opposition parties. While it was clear that Africans wanted the media to play a watchdog role (across 20 countries, 71% agreed that the news media “should constantly investigate and report on corruption and the mistakes made by government,” compared to just 23% who instead agreed that “too much reporting on negative events, like corruption, only harms the country”), they resoundingly rejected a similar role for opposition parties. A clear majority (60%) said that after elections, opposition parties should essentially set aside their differences and “concentrate on cooperating with government and helping it develop the country.” Just 35% thought the opposition should “regularly examine and criticize government policies and actions” and hold it to account.

This finding raised questions about how Africans understand the very concept of “opposition.” There seems to be something of a paradox. Africans clearly support elections as a way of choosing their leaders, and they want to have real choices when they go to the polls. Yet they appear to be uncomfortable with what this means on a daily basis, with the push and pull of politics that is part and parcel of a competitive party system.

A desire to better understand how people view opposition parties and party competition led Afrobarometer to add a special module of questions on leadership and parties to the Round 6 questionnaire. We’re still waiting for all of the data to come in, but early findings based on data from 20 countries include:

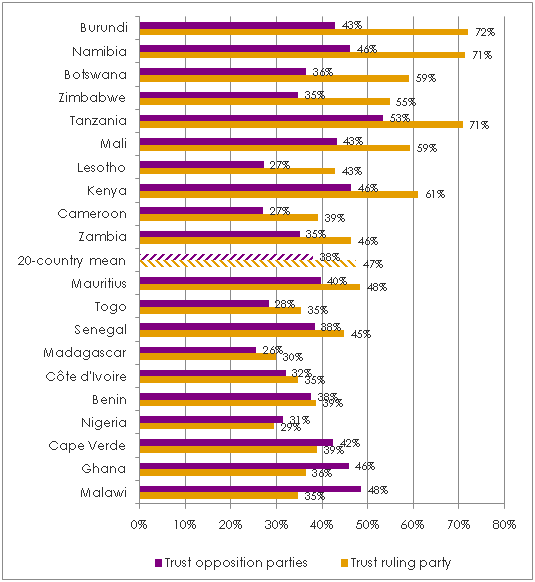

- The trust gap has narrowed, especially in countries that have undergone an alternation; on average it’s down to just 9 points (see Figure 1).But the decrease is due primarily to declining trust in ruling parties, not increasing trust in the opposition.

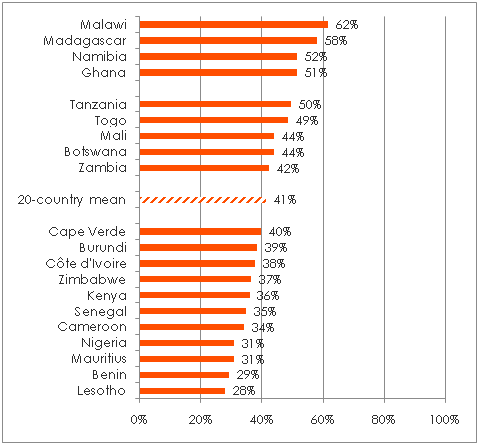

- A plurality (41%) rate the opposition in their country as presenting a “viable alternative vision and plan for the country” – only marginally above the 37% who disagree (see Figure 2).

- If anything, even fewer people now than in Round 3 agree with the notion of opposition parties as watchdogs (see Policy Paper 26).

We’ve started to look at why people think the opposition is or is not viable. The first results indicate that perceptions of viability are strongly linked to levels of trust. But why is trust in the opposition still so weak? Of course, as we watch trust in ruling parties fall toward the same low levels as trust in the opposition, the question may become moot. But for now the gaps, while smaller, are not gone, and beg for explanation.

Perhaps even more important, on a continent still starved of accountable and responsive governance, is the question of why Africans seem to prefer a conciliatory role for opposition parties after elections, rather than unleashing their potential as guardians of the public good in the face of all-too-frequent government predations. Of course, the winnerswill always prefer that the losers keep quiet after the election is over. But the reluctance to see an aggressive, confrontational opposition extends well beyond these winners. I’m hoping that oncewe have the Round 6 data from all 36 countries, we’ll be able to shed some new light on this subject.

Figure 1: Trust in ruling and opposition parties | 20 countries (ordered by size of the trust gap) | 2014/2015

Respondents were asked: How much do you trust each of the following? (% who say “somewhat” or “a lot”)

Figure 2: Opposition as viable alternative government | 20 countries | 2014/2015

Respondents were asked: Please tell me whether you agree or disagree with the following statement: The political opposition in [your country] presents a viable alternative vision and plan for the country? (% who “agree” or “strongly agree”)

Carolyn Logan is deputy director of Afrobarometer and associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Michigan State University.