Originally published on the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, where our regular Afrobarometer series explores Africans’ views on democracy, governance, quality of life, and other critical topics.

Coming off a fifth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, South Africans are contending with an economic storm. High poverty, inflation, and unemployment, along with slow economic growth, have revived proposals for a basic income grant to help those who are struggling.

Many look to the temporary COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress Grant (SRDG), Africa’s largest cash-transfer program — and the fastest-ever rollout — as a model for more permanent income assistance that would provide ongoing monthly payments to unemployed adults. About 40% of South Africans have benefited from the COVID-19 grants introduced in April 2020. Most recipients use these funds to meet immediate household needs such as food, electricity, and toiletries.

But in-depth interviews with 41 South Africans eligible for the grants suggest the government assistance could go further if it were easier — and less expensive — to obtain. On average, recipients report they used about 15% of their grants to cover expenses incurred in accessing the funds. For some recipients these expenses approached 50%.

“A lifeline” in rough seas

About 14 million South Africans, about 24% of the population, were already living in poverty before the pandemic. Deprivation and inequality worsened when President Cyril Ramaphosa launched one of the world’s strictest lockdowns in March 2020. The country continued to enforce lockdowns to varying degrees for much of the next two years. Some sources estimate that by the end of 2020, 2 million South Africans had lost their jobs. One survey reported 47% of households had run out of money to buy food by April 2020.

The government’s package of emergency relief measures included the SRDG, which provides a monthly cash transfer of R350 ($20) to unemployed adults. The South African human-rights organization Black Sash described the package as “a lifeline, but … not enough.” Initially intended to run from May to October 2020, the grant has been extended several times, most recently to March 2023.

Who is getting help?

An Afrobarometer face-to-face survey with 1,600 South Africans in May and June 2021 confirms the challenges many citizens face as a result of the pandemic. While 8 in 10 South Africans (80%) said the country’s strict lockdowns were necessary to curb the spread of the virus, nearly two-thirds (64%) found it difficult to comply with the restrictions.

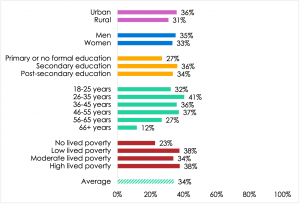

One in three (34%) reported losing a job or primary source of income due to the pandemic. For those aged 26-35, the figure was 41%, as shown in Figure 1; for the poorest citizens, it was 38%.

Figure 1: South Africans who lost their primary income due to the pandemic | Afrobarometer 2021

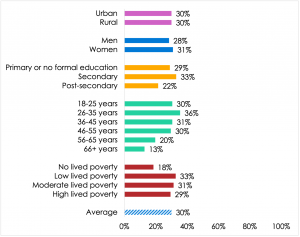

But nearly as many (30%) reported receiving some form of COVID-19 relief assistance from the government (see Figure 2). South Africans aged 26 to 35 — the group most likely to report a loss of livelihood — were also the most likely to receive support (36%), along with poorer and less-educated respondents.

Figure 2: Who got COVID-19 relief assistance from the South African government? | Afrobarometer 2021

But applying for help costs money

For some beneficiaries, the SRDG spelled the difference between eating and going hungry. In qualitative interviews focusing on understanding people’s experiences accessing the SRDG in a Cape Town township (Khayelitsha) and a town in the Eastern Cape province (KwaBhaca) between July and October 2021, one of our respondents explained, “There were days where we would run out of food, and when the day comes for me to go and get my grant, I would buy potatoes. With my first payment I bought potatoes, 10kg of rice, and we were able to eat something with my family.”

But before they can use the money to meet their basic needs, South Africans have to apply for the grant and then secure access to the funds at a post office (since May, some grocery stores have also offered access). Collecting the actual grant money can drain away a significant share of the support: On average, recipients we interviewed spent R50 ($3) to acquire their grants; some had to spend as much as R160 ($10), or nearly half of the grant funds.

Applying via the government’s online portal forces some citizens to incur data costs — assuming they have Internet access and are familiar with online transactions. But survey participants reported the most significant expenses involve travel costs to collect the funds, especially for rural residents. In addition, some recipients spent hours in long queues, or had to stay overnight or even make multiple trips before securing their monthly payment. Network problems and poor service from post office staff sometimes disrupted delivery of the funds, participants noted.

More nefarious (but common) costs include corruption on the part of some post office officials, who reportedly find illegal routes to claim a share of the grant funds. And there are reports of organized extortion in the queues, with some beneficiaries reporting they felt forced to pay security guards or others to access the queues or hold their places.

Here’s an example of the challenges each month, based on the experiences of one SRDG recipient we interviewed. Mpilo reported he had to borrow the R100 ($6) bus fare, then got up at 2 a.m. to catch the bus, reaching the post office in the early morning to find people who had slept there overnight. He waited in the queue all day before finally receiving his funds late in the afternoon, leaving behind a full queue with some people fighting for places in line. He also described occasions when the system would shut down and everyone would be told to go home and return the next day.

In 2022, with South Africa experiencing its highest inflation rate in 13 years, the buying power of the grants is declining. The high costs that many beneficiaries incur to collect their grants risk undermining an important safety net — and could leave millions of South Africans hungry. Regardless of whether the SRDG evolves into a basic income grant, improving systems for accessing the funds could provide significant and immediate benefit to many of the country’s most vulnerable.