Originally posted on Deutsche Welle.

With presidents changing constitutions to stay in power and political opponents ending up behind bars, there's a popular belief that democracy in Africa is dying. But experts say there's actually a lot of good news.

The decision by President Kabila to postpone elections several time has led to anger and protests in the Democratic Republic of Congo

From an outsider's perspective, the heydays of African democracy are long gone. Scrapping term-limits to remain in power has become a popular sport for rulers like Uganda's Yoweri Museveni. Others, such as Congo's Joseph Kabila have postponed elections and only bowed to national and international pressure after several years of negotiations. When elections do take place, like in Zimbabwe this July, they are often marred by fraud claims.

Still, African scholars like Ghana's Emanuel Gyimah-Boadi believe there is a reason for optimism. "Africans want democracy and they are prepared to push for it," the former professor of political science at the University of Ghana says. But that's not just his personal assessment. As co-founder of Afrobarometer, a pan-African research network, he has spent close to two decades conducting public opinion surveys. And they paint a clear picture: seven out of 10 respondents say that they support democracy in Africa. Almost 80 percent reject military rule. The removal of presidential term-limits is also unpopular, with 75 percent of respondents supporting a two-term limit for presidents.

Taking to the streets in the defense of democracy

Gyimah-Boadi says that Africa's quest for democracy is not just visible in numbers, but also in day to day life. "You see it on the street, you see it in the courts, you see this in the media, you see this online, you see this in the campaigns of opposition activists: you see the citizens taking great risks to push for more democracy, more human rights and more justice."

Emanuel Gyimah-Boadi says that many Africans are supporting democracy

In fact, the scrapping of term limits in Uganda last year was marred by mass demonstrations. Time and again, protestors defied deadly police violence to rally against Congo's president Joseph Kabila. Early last year, protestors in The Gambia, with the help of the regional economic bloc ECOWAS, succeeded in forcing out Gambia's dictator Yahya Jammeh who refused to hand over power after he had lost in elections.

Other scholars also reject the view that African democracy is a dying breed. "During the Arab spring, people were asking for the African spring, but the African spring had already happened before and was much more sustainable than the Arab one," says Matthias Basedau, director of Germany's GIGA Institute of African Affairs. The African spring refers to a period in the early 1990s where mounting pressure from citizens and increased donor pressure forced a number of African dictators to quit.

High demand, but not enough supply

Some countries have slipped back into authoritarian rule in the meantime, but Basedau's colleague Charlotte Heyl is also among those who believe that much progress has been made. "Elections are the most important mode for the transfer of power today," Heyl told DW. "Today, political power is most often transferred through elections, twice as often as through violent means such as coup d'etats. That's a very interesting difference to the period after independence."

President Museveni's decision to scrap the constitutional age limit for presidents spark outrage in Uganda

But while Africans might demand democracy, it does not automatically mean that they will get it. "Popular demand is only being fulfilled to a certain degree", Gyimah-Boadi says. That's what Afrobarometer surveys also indicate: only 51 percent of respondents say that they are living in a country with full democracy. Only 43 percent say that they are satisfied or very satisfied with democracy in their home countries. Interestingly, satisfaction with democracy varies greatly depending on the region the respondents are living in: while 59 percent of East Africans are satisfied with democracy, only 46 percent of West Africans and 18 percent of residents of Central Africa are satisfied with the state of democracy.

Western countries – friends or foes?

To satisfy the quest for democracy in Africa, donors must make sure that they do not contradict the development of democratic structures, Gyimah-Boadi says. "My plea to Germany, the European Union or the G7 countries is: do not retreat from the promotion of democracy and good governance, because doing so will be out of sync with what African citizens want and will only strengthen the hands of non-liberal democratic influences you are worried about."

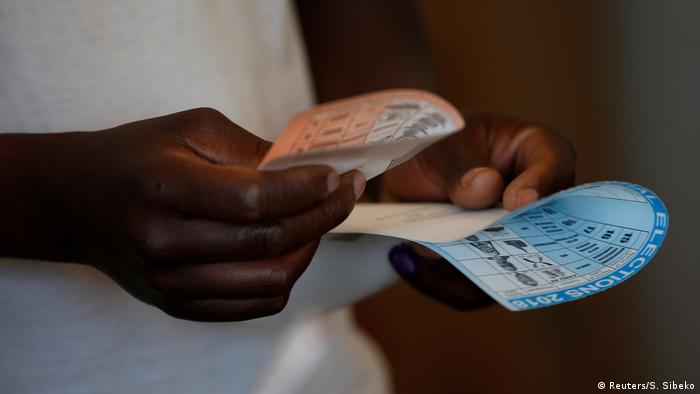

Elections in Africa are often marred by fraud claims

Critics say there is growing trend among donors to disregard democratic values in their partnerships with African countries. Western countries like Germany seem increasingly willing to cooperate with authoritarian regimes in order to control migration flows to Europe. Countries with authoritarian governments, such as Rwanda or Egypt, participate in the "Compact with Africa," Germany's flagship program for the continent. In October, a conference with the presidents of the 'compact countries,' hosted by Chancellor Angela Merkel in Berlin, drew angry crowds of protestors who complained about the inclusion of these governments.

GIGA's Matthias Basedau, however, says that even good-will from donors alone would not make democracy in Africa a self-starter. "We should not think that democracy in Africa is mainly dependent on support from Germany or other European countries. It is something that needs to be achieved by Africans themselves."