The latest Afrobarometer surveys could help government messaging on fighting the delta variant.

Originally published on the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, where our Afrobarometer Friday series explores Africans’ views on democracy, governance, quality of life, and other critical topics.

By Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny

In early August, the World Health Organization recorded Africa’s highest-ever weekly COVID-19 death toll — more than 6,400. Variants are fueling increases in infections, especially among young people.

As African governments confront the latest pandemic wave, how can citizens’ views of earlier surges inform their strategies?

Afrobarometer’s face-to-face interviews with 17,800 citizens in 14 African countries between late 2020 and mid-2021 show that citizens largely approve of strong government action to limit the spread of COVID-19. But they don’t trust their governments when it comes to resources and vaccines.

Good news, bad news on government performance

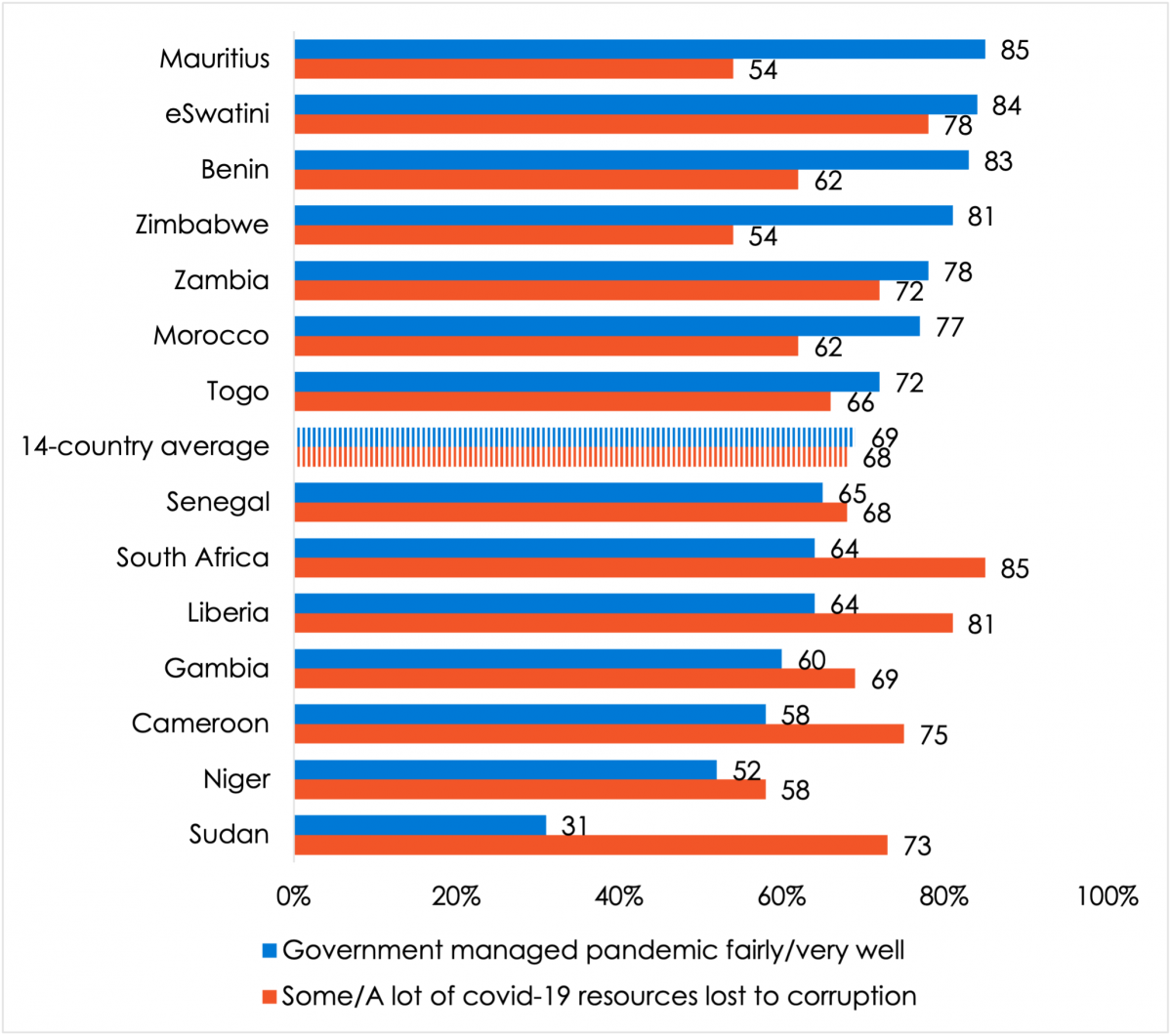

Afrobarometer reported earlier on public perceptions on the pandemic from five West African countries — and these patterns hold true across this larger sample, which includes southern and North African countries. Across 14 countries, more than two-thirds (69%) of respondents say their government has done a “fairly” or “very” good job of managing the pandemic response. More than 8 in 10 citizens approve of government action in Mauritius, eSwatini, Benin and Zimbabwe. Sudan is the exception: Just 31% there agree (see Figure 1).

In the 11 countries that experienced national lockdowns, 77% of respondents endorse these restrictions as necessary steps, even though 68% found it difficult to comply and 33% say someone in their household lost a job, a business or a primary source of income due to the pandemic.

Two-thirds of respondents (64%) also approve of school closings, although 79% think the schools should have reopened sooner.

But views are far less positive when it comes to government management and distribution of pandemic-related resources. Only 30% of households report receiving some form of special government assistance. And twice as many (61%) say their government distributed aid unfairly.

More than two-thirds (68%) believe that corrupt government officials stole “some” or “a lot” of the resources available for the pandemic response. South Africans (85%) and Liberians (81%) have a particularly jaundiced view of their government’s integrity, but this was the majority assessment in every surveyed country.

Figure 1: Government performance and corruption in the COVID-19 response |Afrobarometer

Vaccine challenges

If citizens’ feedback offers African governments some encouragement — as well as impetus for improving the handling of pandemic-related resources — this information also highlights major challenges when it comes to COVID-19 vaccination.

The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention is aiming to help governments vaccinate 20% of Africans by year’s end, but as of mid-August, only about one-tenth of that target had been met. Vaccine supplies, though improving, are still staggeringly inadequate.

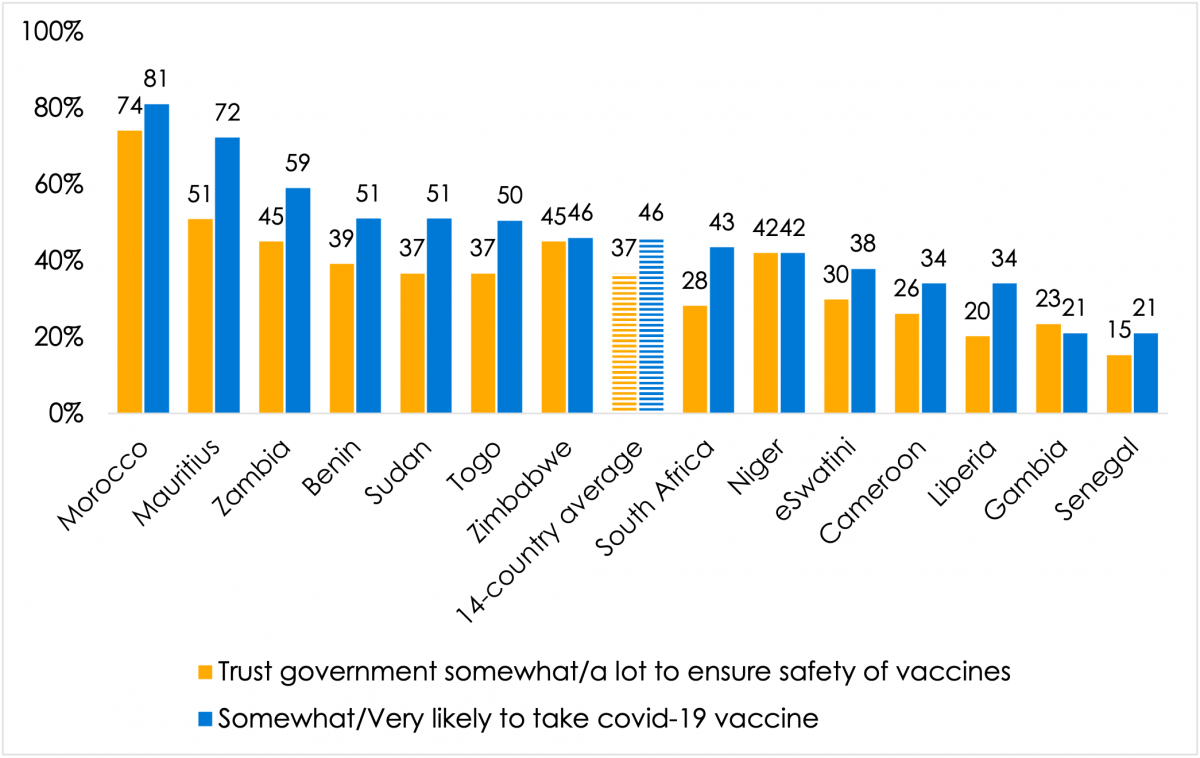

But a good supply of vaccines, once available, will encounter significant vaccine hesitancy. On average across the 14 countries, fewer than half (46%) of Africans say they are “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to try to get vaccinated (see Figure 2).

Morocco, which has recorded the continent’s second-most COVID-19 cases and highest number of administered vaccines, reports the highest level of vaccine acceptance: 81% of respondents say they will probably try to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Mauritius ranks second, with 72%.

But majorities in 8 of the 14 countries are vaccine hesitant. Only 21% of Senegalese and Gambians, and 34% of Liberians and Cameroonians, say they are likely to try to get the vaccine. Even in hard-hit South Africa, only 43% say they want to be vaccinated.

Figure 2: Do Africans trust their government — and COVID-19 vaccines? |Afrobarometer

Who wants the vaccine?

On average, vaccine readiness is higher among older, urban and economically better-off people. But patterns vary by country, which suggests that a detailed analysis may be helpful to each government’s efforts to build effective communications strategies.

Somewhat surprisingly, in 9 of the 14 countries, less-educated citizens are more willing to get vaccinated. The vaccine-willingness spread between those with no formal education and those with post-secondary schooling reaches 23%age points in Zimbabwe and 21 points in eSwatini. Liberia, the Gambia and Sudan are the only countries where more educated citizens are more likely to accept vaccines.

Willingness to get vaccinated increases with age in 9 of the 14 countries as well. Elders (those age 56 and up) outstrip young adults (ages 18-35) in vaccine readiness by 27%age points in eSwatini and by 14 to 16 points in the Gambia, Cameroon and South Africa. But in Liberia and Togo, young adults are more likely to want the vaccine than their elders.

Is this a question of trust?

Analysts have identified a variety of factors that may contribute to vaccine hesitancy, including skepticism about its effectiveness, fear of side effects and the myth that COVID-19 is not a threat for Africa. Anti-vaccine misinformation efforts have promoted these messages. Another factor is trust: Research shows that low trust in government integrity or capacity leads to low compliance with preventive health policies.

Across the 14 countries surveyed, fewer than 4 in 10 citizens (38%) trust government statistics on COVID-19, and a similar minority (37%) trust their government “somewhat” or “a lot” to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines are safe (see Figure 2).

Morocco, which pursued a rigorous pandemic response that includes a partnership with China to set up a domestic vaccine-production facility, is the only country where a strong majority (74%) trust the government to ensure vaccine safety. Countries with the least inclination to get vaccinated — Senegal, the Gambia, Liberia and Cameroon — also record the lowest confidence (just 15-26%) in their governments’ ability to ensure that vaccines are safe.

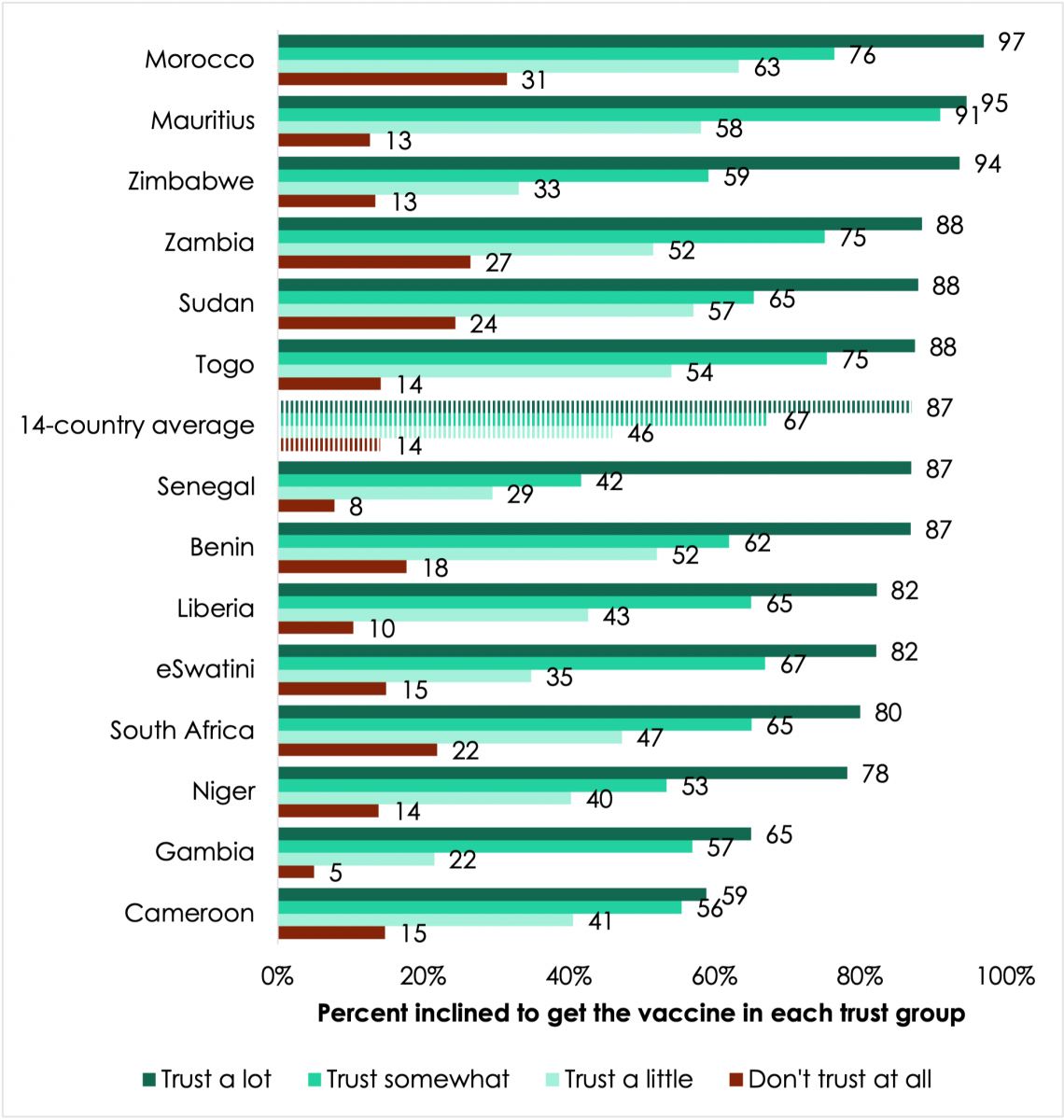

This trust matters: Those who trust their government “a lot” on vaccine safety are 3 to 13 times as likely to want the vaccine as those who don’t trust it at all (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Likelihood to seek vaccination, by level of trust in government to ensure COVID-19 vaccine safety | Afrobarometer

Looking ahead

Approval of government performance and mistrust on resources and vaccines may not add up to a coherent whole. Africans, like their governments, are still struggling to make sense of this bewildering pandemic.

But for policy makers, these survey findings indicate a clear message from citizens: People will accept restrictions, even if they hurt, but they won’t overlook corruption and unfairness. And they are largely unpersuaded when it comes to vaccines.

Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny (@JAppiahNyamekye) is knowledge translation manager for Afrobarometer