Originally published on The Africa Report site.

Regardless of who wins the US elections in November, analysts have argued that a process of updating and revitalising US policy towards Africa is overdue.

New data from Afrobarometer’s latest round of public attitude surveys conducted across 18 African countries during 2019/2020 provide several guideposts for US policy makers.

Why should the voices of ordinary Africans matter to US Africa policy? American policy must take account of the increasingly competitive environment for opportunities and influence in Africa, especially in the context of China’s growing engagement on the continent.

A forward-looking Africa policy must therefore address areas of mutual interest to both the US and African governments – and to their public.

Across much of Africa, elections increasingly play a real role in selecting and replacing leaders – they are no longer merely a rubber stamp for the ambitions of unchallenged incumbents. A foreign policy informed by what the public want is a pragmatic necessity.

For policy makers and analysts, we highlight Africans’ priorities and preferences with regard to sovereignty and self-sufficiency, democracy and accountability, and investment – in jobs, health, infrastructure, and education.

Sovereignty and self-sufficiency

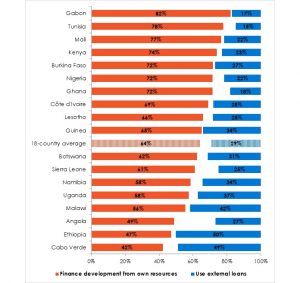

Africans are not looking for a handout, and may increasingly recognise the costs – both political and financial – of high indebtedness. When Afrobarometer asked whether countries should “finance development from their own resources, even if it means paying more taxes,” or rely on external loans, respondents favored self-reliance by more than a 2-to-1 margin (64% vs. 29%). [Figure 1]

These aspirations to self-sufficiency do not mean Africans reject international assistance. But they prefer to retain local control and resist imposition of conditions on external loans or development assistance: 54% insist that their governments should make their own decisions about how loans and development assistance are used, compared to 42% who prefer that the countries providing the funds strictly enforce requirements on how funds are used.

A smaller majority also dislike aid conditionality, even when it is designed to promote democracy and human rights (50 percent oppose conditionality, 45 percent favor it).

Conditionality has traditionally marked a key distinction between the Western approach, which uses aid as a carrot to promote liberal reforms, and China’s more hands-off approach. Threading the needle of meeting US policy goals for development assistance while respecting African sovereignty and the desire for self-directed development will be one of the particular challenges for a revitalised US Africa policy.

Democracy and accountability

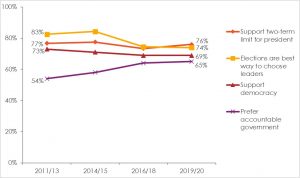

Africans express consistently strong support for democratic norms and accountable governance. Across the 18 countries included in the most recent surveys, nearly seven in 10 respondents (68%) express a preference for democracy, and this figure remains relatively steady across the 15 countries tracked since 2011.

Even larger percentages reject strongman rule (81% ), one-party rule (76%), and military rule (73%). In addition, a large (albeit declining) majority still see the ballot box as the sole legitimate method for choosing leaders, and support for limits on presidential tenure is strong and steady.

There is also an increasing recognition in the importance of accountability: Across 15 countries tracked since 2011, preference for having an accountable government over one that “can get things done” has increased by more than 10 percentage points, from 54% to 65%. [Figure 2 ]

This suggests that democracy is valued even if it comes with costs. A values-led foreign policy that reinforces democratic norms and accountable governance should meet with public support, even if it rankles incumbent autocratic leaders. Dictators are not welcome, even if they claim to offer effective governance.

Policy priorities: Investment

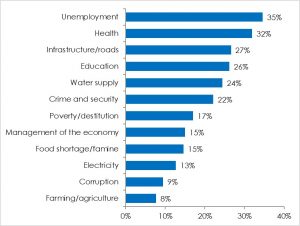

Afrobarometer also asks respondents to identify “the most important problems that government should address,” recording up to three responses per person. Jobs (mentioned by 35% of all respondents) and health care (32%) top the list, followed by infrastructure/roads (27%), education (26%), and water supply (24%). [Figure 3]

US foreign aid already places a high priority on health, spending more than $4bn in this sector in sub-Saharan Africa in 2018. After emergency response, health (including HIV/AIDS spending) is the largest category of American foreign assistance to Africa. Given the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, even higher levels of investment may be forthcoming.

However, if the US government wishes aid expenditures to be fully appreciated, it may want to prioritise aid that leads (directly or indirectly) to job creation, while making the case that investment in areas such as education, agriculture, and infrastructure also leads to economic growth and jobs. Employment remains the most central popular concern in many African countries, ranking well above current US priority sectors such as conflict, peace, and security.

Even if the United States is unable to match China’s pledged $60bn in loans and aid to the continent, it can maximise the impact of its available resources by building a policy that is consistent with the aspirations and values across Africa.

Related content