- On demand for democracy: For the most part, African citizens are committed to democracy. Most indicators of support for democracy and democratic institutions remain strong and quite steady.

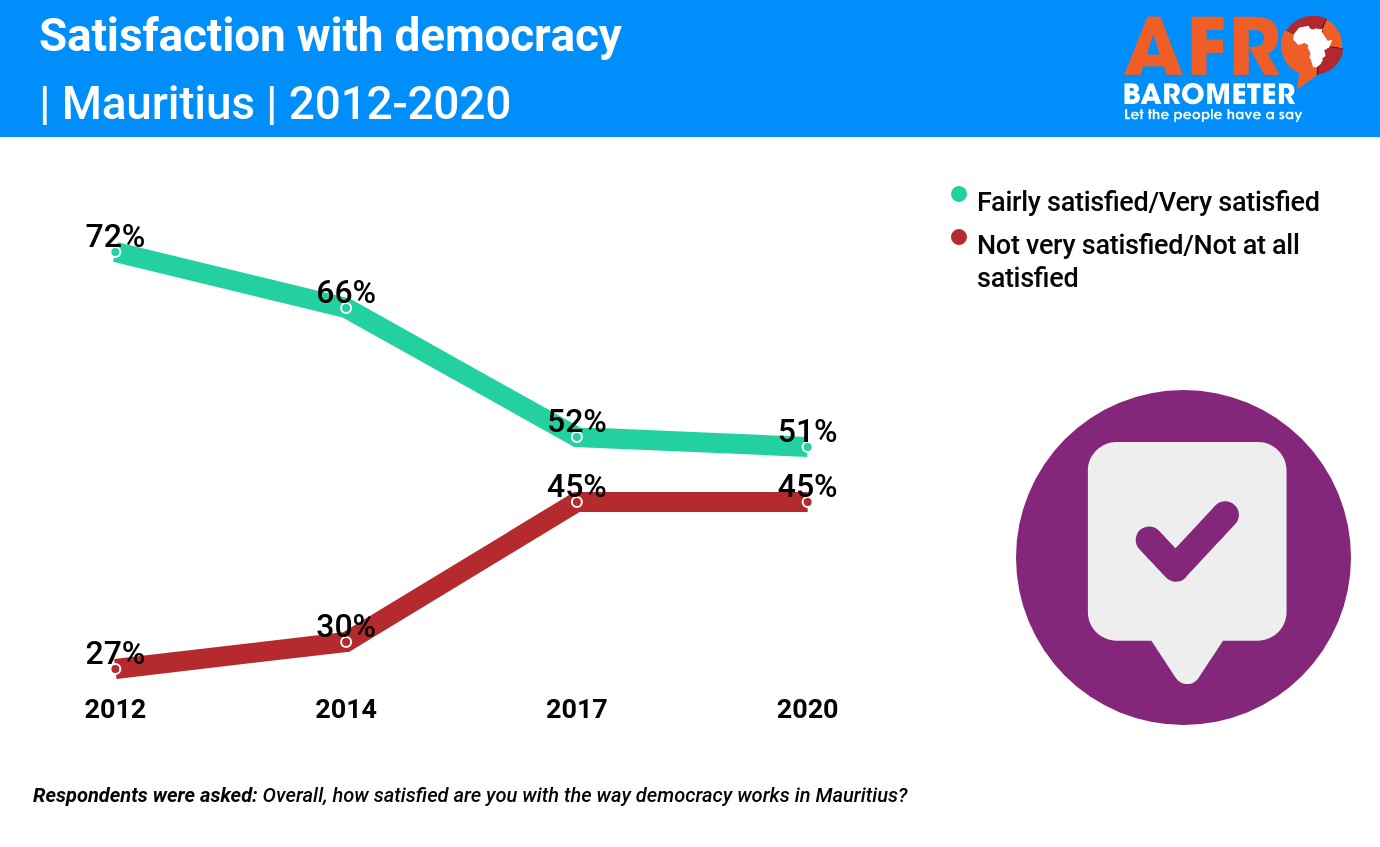

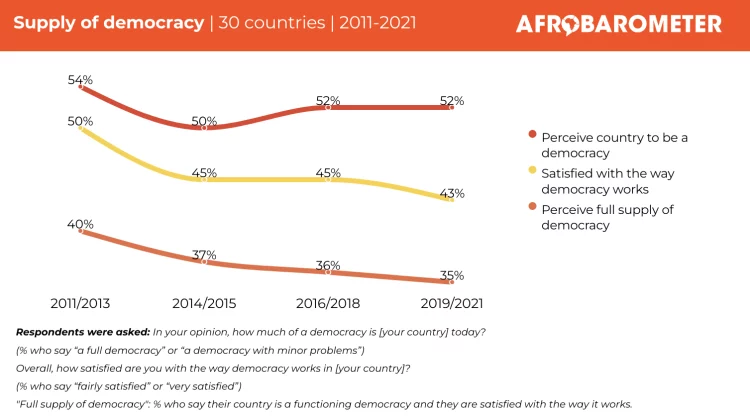

- On supply of democracy: Indicators of supply largely lag behind those for demand, and have tended to decline over the past decade. Fewer people think their countries are democracies, and satisfaction with democracy is even lower, and dropping faster.

- On democratic attitudes among young people: Compared to their elders, citizens aged 18-30 show stronger commitment to democracy on some indicators, especially those related to the importance of multiparty competition, but slightly lower support for elections and for democracy overall.

The last several years in Africa have been marked by both encouraging democratic highs and troubling anti-democratic lows. Bright spots include the Gambia’s successful 2021 presidential election, the 2021 ruling-party transition in Zambia, and the first democratic transfers of power in Niger (2020/2021) and Seychelles (2020). We can add the February 2020 decision by Malawi’s Constitutional Court to annul the results of the country’s flawed 2019 presidential election and call for a new election, and the ouster of long-running autocrats in Sudan and Zimbabwe.

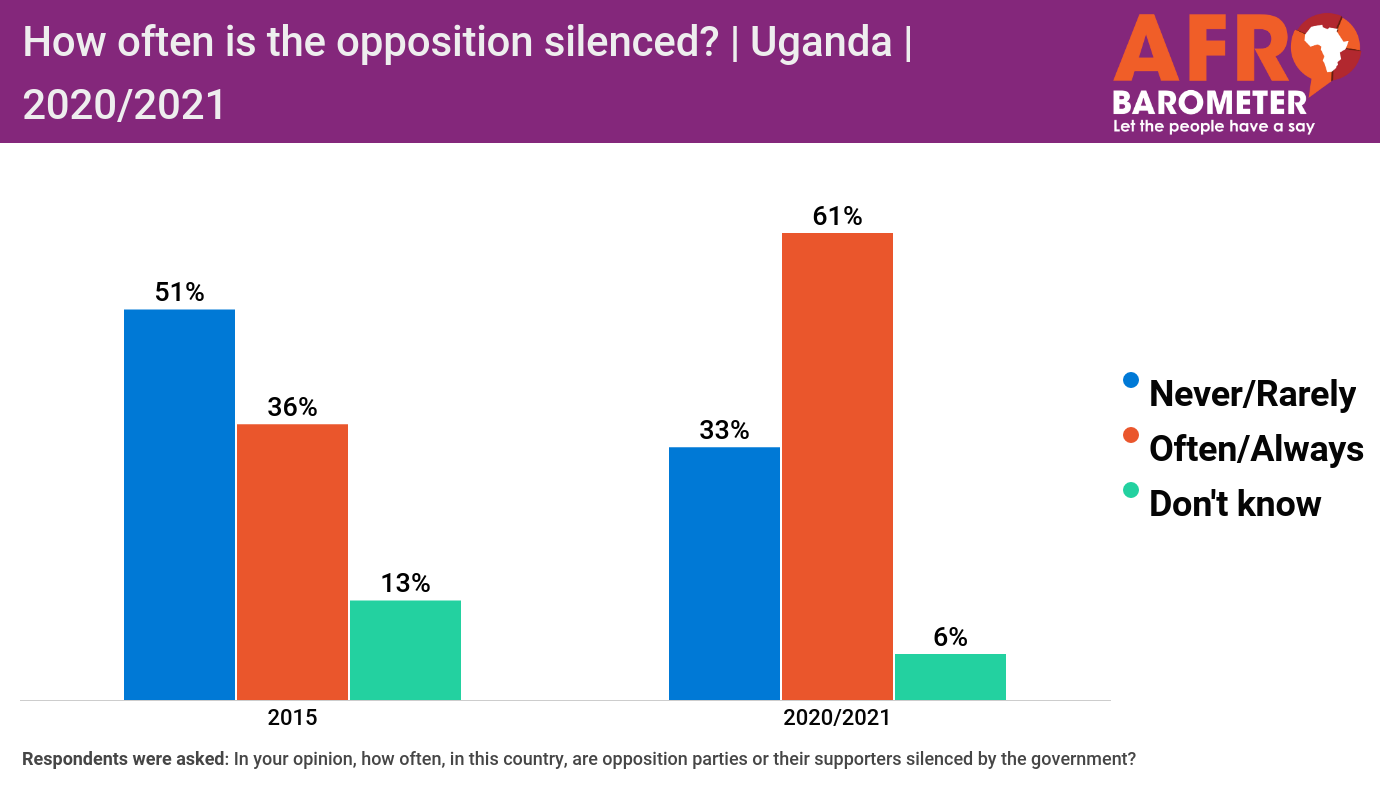

Contrast these gains, though, with setbacks elsewhere, including increasing restrictions on opposition parties in Benin, Senegal, and Tanzania; the use of vote rigging, violence, and intimidation during elections in Côte d’Ivoire and Uganda; and a wave of recent military coups in Chad, Mali, Sudan, and Guinea in 2021 and two in Burkina Faso just in 2022.

The continent’s most autocratic incumbents appear at times to have been emboldened in wielding anti-democratic tactics by factors such as the West’s increasing focus on combating violent extremism and rising insurgency; the growing influence of China and Russia; the indifference, or even hostility, of these and other African development partners to democratic governance; and the cover that the COVID-19 pandemic has sometimes offered for limiting freedoms, restricting fair campaigning, or postponing elections.

These contradictory developments have contributed to dire warnings from experts that democracy is losing ground in Africa. But what can we learn about the state of democracy on the continent from Africans themselves? How are these developments in the African democratisation project reflected in trends in popular attitudes toward democracy? Are these efforts to either undermine or promote and defend democracy evident in the views of ordinary citizens?

Afrobarometer’s Round 8 surveys took place across 34 countries during 2019-2021, alongside many of these democratic highs and lows, and straddling the onset of the pandemic. And the findings reveal that, for the most part, Africans remain committed to democracy. We find that despite the many efforts to undermine democratic norms and freedoms, citizens continue to adhere to them. They believe that the military should stay out of politics, that political parties should freely compete for power, that elections are an imperfect but essential tool for choosing their leaders, and that it is time for the old men who cling to power to step aside.

But their political reality often falls short of these aspirations: It is often the supply of democracy that citizens find lacking. The perception of widespread and worsening corruption is particularly corrosive, leaving people increasingly dissatisfied with political systems that are yet to deliver on their aspirations to live in societies that are democratically and accountably governed. And although citizens find myriad ways to voice their concerns, they feel that their governments are not listening.

Simply put, Africans want more democratic and accountable governance than they think they are getting.