- Lived poverty varies widely across the continent. In Mauritius, people rarely endured shortages of a basket of basic necessities (food, clean water, health care, cooking fuel, and a cash income) during the previous year. At the other extreme, the average Guinean and Gabonese reported that they frequently went without several of these basic necessities.

- Lived poverty is clearly moving upward, reversing a decade-long trend of steadily improving living conditions that we saw coming to an end in Afrobarometer Round 7 surveys in 2016-2018. For countries that have conducted the longest time series of surveys, deprivation of basic necessities captured by our Lived Poverty Index has returned to the same levels as measured in 2005-2006. The trend is similar for “high lived poverty,” the proportion of people who experience frequent shortages of basic necessities.

- Increases in national levels of lived poverty over the past decade tend to be largest in countries where the economy has stagnated or contracted, as measured by changes in GDP per capita.

- Comparing levels of lived poverty recorded in Round 7 and Round 8 surveys, there was no statistically significant difference in the extent of change based on whether the Round 8 survey was conducted before or after COVID-19 lockdowns.

- However, among countries whose Round 8 survey followed the first wave of COVID-19, more stringent government responses were associated with larger increases in lived poverty. And increases in poverty were also larger where higher percentages of respondents told interviewers that it had been difficult to comply with these restrictions.

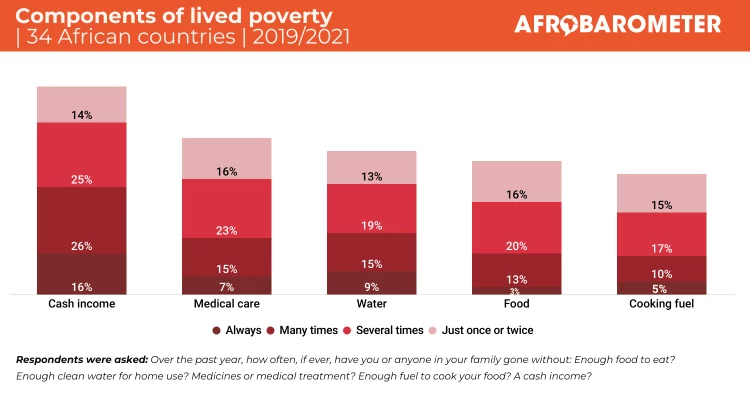

Lived poverty – measured as the frequency with which people go without basic necessities – declined steadily in Africa between 2005 and 2015 (Mattes, Dulani, & Gyimah-Boadi, 2016), a trend matched by consumption-based estimates of poverty produced by the World Bank (2018). However, results from Afrobarometer Round 7 surveys (conducted in 2016/2018) suggested that the decade-long trend of improving living standards had come to a halt and that lived poverty was once again on the rise (Mattes, 2020).

The most recent findings, from Afrobarometer Round 8 surveys conducted in 34 African countries between July 2019 and July 2021, confirm that deprivation is indeed resurgent. This trend has its roots in a continent-wide slowdown that began in 2014: Economic growth decelerated sharply in 2016, and turned to economic contraction in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Increases in national levels of lived poverty tend to be largest in countries where the economy has stagnated or contracted, measured by changes in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

But the way African governments reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic has also shaped trends in poverty: Among countries whose Round 8 survey followed the first wave of COVID-19, more restrictive government responses were associated with larger increases in lived poverty. And increases in poverty were also larger where higher percentages of respondents told interviewers that it had been difficult to comply with these restrictions.