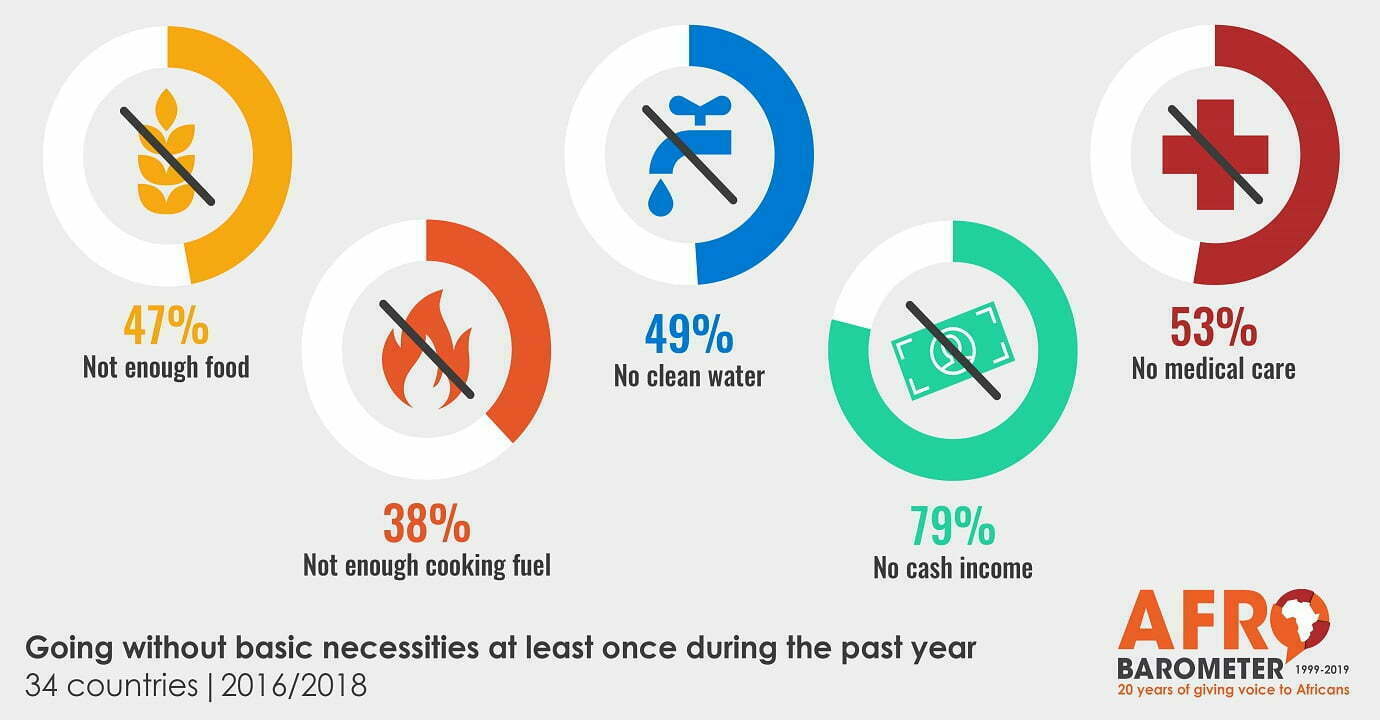

Economic destitution – whether measured as the frequency with which people go without basic necessities or as the proportion of people who live on less than $1.90 a day – declined steadily in Africa between 2005 and 2015. However, the findings of Afrobarometer Round 7 surveys, conducted in 34 African countries between late 2016 and late 2018, demonstrate that improvements in living standards have come to a halt and “lived poverty” is once again on the rise.

To prevent squandering hard-won gains in Africans’ living standards, the data point to the necessity of a renewed commitment by citizens, governments, and international donors to defending democracy and expanding service-delivery infrastructure.

Key findings

- Between 2005 and 2015, Afrobarometer surveys tracked a steady improvement in the living conditions of the average African. Measured as the frequency with which people go without a basket of basic necessities (food, clean water, health care, heating fuel, and cash income), “lived poverty” dropped in a sustained fashion over this period – a trend matched by consumption-based estimates of poverty by the World Bank.

- The most recent Afrobarometer surveys, however, suggest that Africa is in danger of squandering these gains in living standards. While the citizens of most African countries are still doing better than they were in 2005/2006, deprivation of basic necessities – captured by our Lived Poverty Index – has increased in about half of surveyed countries since 2015. The trend is similar for “severe lived poverty,” the extent to which people experience frequent shortages of basic necessities.

- Lived poverty varies widely across the continent. At one extreme, people rarely experience deprivation in Mauritius. At the other, the average person went without several basic necessities several times in the preceding year in Guinea and Gabon. In general, lived poverty is highest in Central and West Africa, and lowest in North Africa.

- Lived poverty also varies widely within societies. Reflecting the legacies of the “urban bias” of successive post-independence governments, rural residents continue to endure lived poverty far more frequently than those who live in suburbs and cities.

- A multilevel, multivariate regression analysis of more than 40,000 respondents across Africa reveals that people who live in urban areas, those who have higher levels of education, and those who have a job (especially in a middle-class occupation) are less likely to live in poverty, as are younger people and men.

- But besides personal characteristics, we locate even more important factors at the level of government and the state. First, Africans who live in countries with longer experiences of democratic government are less likely to live in poverty.

- Second, people who live in communities where the state has installed key development infrastructure such as paved roads, electricity grids, and piped-water systems are less likely to go without basic necessities. Indeed, the combined efforts of African governments and international donors in building development infrastructure, especially in rural areas, appears to have played a major role in bringing down levels of poverty – at least until recently.

Related content