Climate change is “the defining development challenge of our time,” and Africa the continent most vulnerable to its consequences, according to the African Union (2015) and the United Nations (UN Environment, 2019). Farmers in Uganda waiting endlessly for rain (URN, 2019), cyclone survivors in Mozambique and Zimbabwe digging out of the mud and burying their dead (Associated Press, 2019) – these images bring home what changing climate and increasingly extreme weather conditions may mean for everyday Africans.

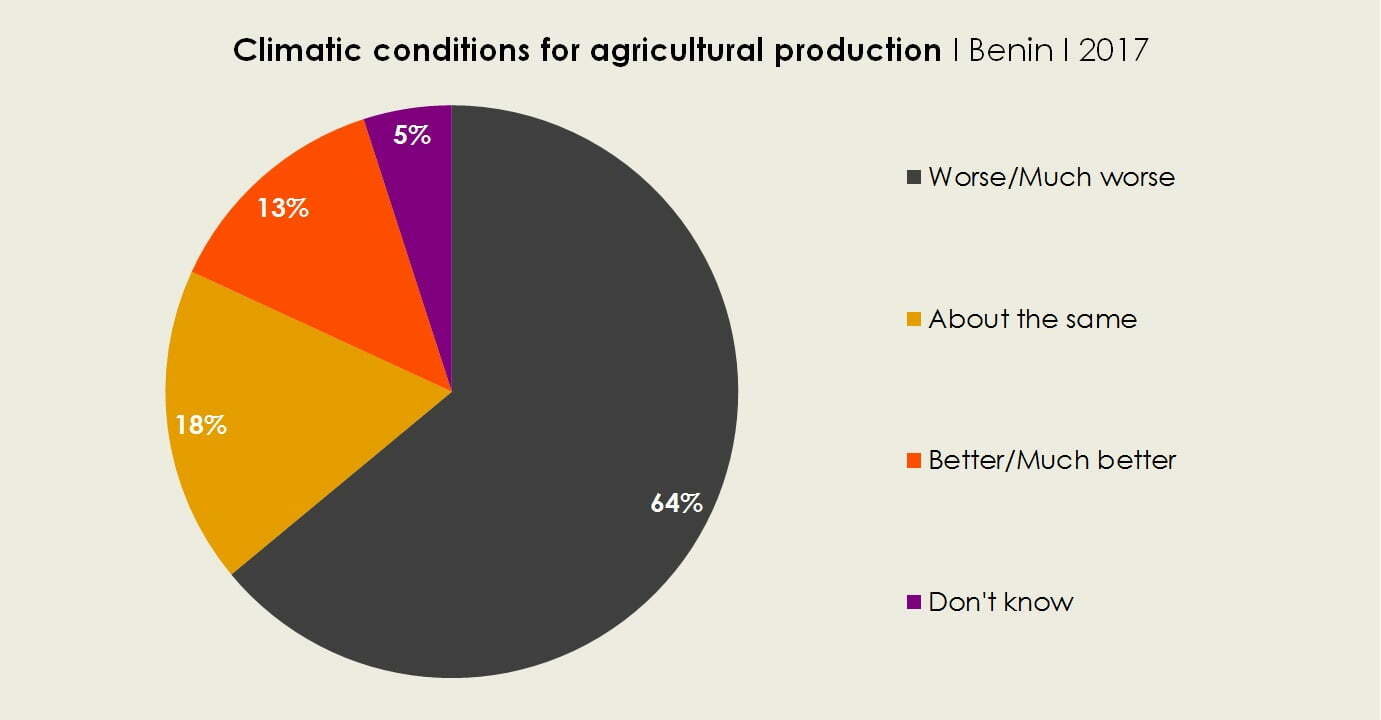

Long-term changes in temperatures and rainfall patterns are a particular menace to Africa, where agriculture forms the economic backbone of development priorities such as food security and poverty eradication (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2018). As an issue, “climate change” per se does not register among the “most important problems” that Africans surveyed by Afrobarometer want their governments to address (see Coulibaly, Silwé, & Logan, 2018). But concerns about the effects of climate change may be embedded in some of the other priorities identified, including water supply (cited by 24% of respondents), food shortages (18%), and agriculture (17%). And progress in addressing these priorities may be seriously impeded by a changing climate. African countries dominate the bottom ranks in the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Index (2019), meaning they are the world’s countries most vulnerable to and least prepared for climate change.

Despite the continent’s minuscule contribution to the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, most African countries have willingly signed on to international agreements to fight it, including the United Nations’ Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol, and the 2016 Paris Agreement on Climate Change (United Nations, 2019). The Paris Agreement mobilizes worldwide action to limit further temperature increases and to strengthen the ability of countries to deal with the impacts of climate change, including a commitment from developed countries to allocate $100 billion by 2020 for climate adaptation and mitigation needs of developing countries (Munang & Mgendi, 2017; UN Climate Change, 2018).

In March 2019, policymakers and key stakeholders from all 54 African countries gathered in Accra for Africa Climate Week 2019 to lay plans to be presented at the UN Climate Action Summit in New York in September (UN Climate Change, 2019). The United Nations has summed up its pressing demand for climate action in its Sustainable Development Goal No. 13: “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts,” calling on countries to integrate climate-change measures into national policies and strategies, strengthen resilience to climate-related hazards and natural disasters, and build awareness and capacity for early warning and impact reduction (United Nations Development Programme, 2019).

Many African governments have laid out their countries’ vulnerabilities in agriculture, water resources, food security, livelihoods, and other sectors and have incorporated climate-change mitigation in national plans (see, for example, Uganda’s Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, 2018, and Ministry of Water and Environment, 2015).

But building climate resilience will require a committed and coordinated effort (Busby, Smith, White, & Strange, 2012), backed by significant resources and a population that understands and supports the need for prioritizing climate change. How do ordinary Africans see climate change? Does talk of urgent action align with their experiences and needs?

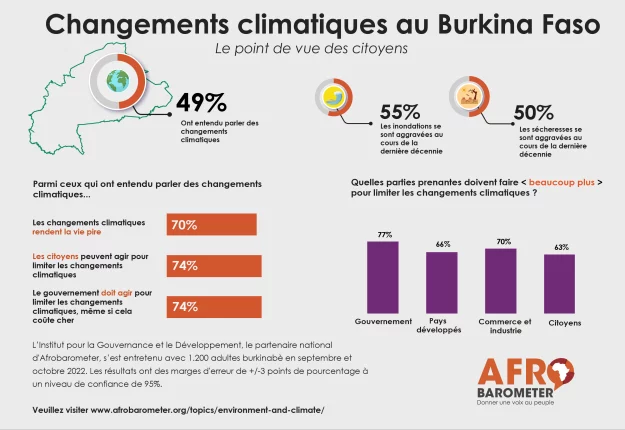

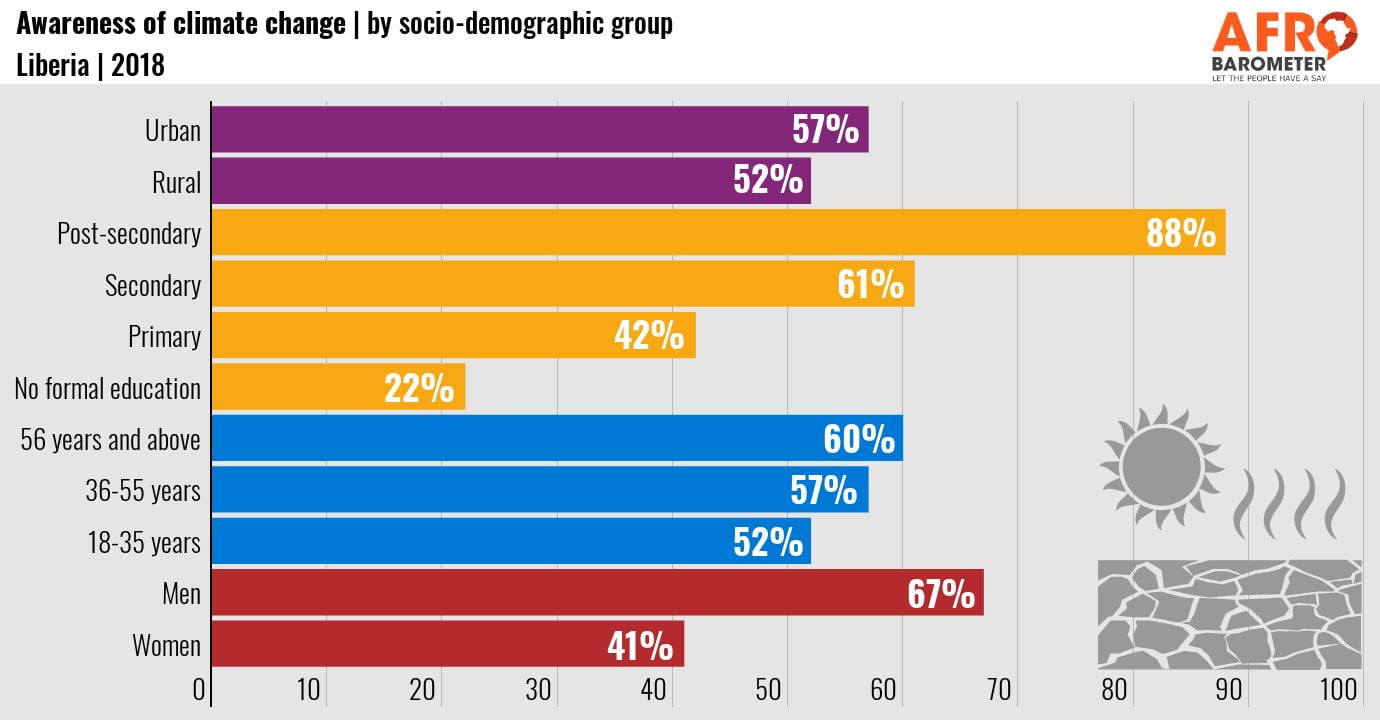

Findings from Afrobarometer’s latest round of public-opinion surveys across Africa show a keen awareness of climate change in some countries – often backed by personal observation – but the opposite in others. Across the continent, among people who have heard of climate change, a large majority say it is making life worse and needs to be stopped. But four in 10 Africans are unfamiliar with the concept of climate change – even, in some cases, if they have personally observed detrimental changes in weather patterns. And only about three in 10 are fully “climate change literate,” combining awareness of climate change with basic knowledge about its causes and negative effects. Groups that are less familiar with climate change – and might be good targets for awareness-raising and advocacy in building a popular base for climate-change action – include people working in agriculture, rural residents, women, the poor, and the less-educated.