Decentralization occurs when resources, power, and tasks are delegated to local-level governance structures that are democratic and largely independent of central government (Manor, 1999). Decentralization can thus be an important vehicle for ensuring that sustainable development policies and programs are implemented at the local level and bring socio-economic relief to the grass roots.

This reasoning has led many African countries to embrace decentralization over the past three decades, often with country-specific expectations. In Egypt, for example, the government argued for deepening democracy and enhancing community partnerships in pursuing decentralization (Nazeef, 2004). Ethiopia sought to improve political representation and public services for different ethnic groups (International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2004). In South Africa, decentralization became an essential component of the transition from apartheid to democracy, notwithstanding the fact that it was demanded by the predominantly white National Party for the parochial interest of having control in some jurisdictions after losing political power to the African National Congress (USAID, 2009).

In Ghana, decentralization is enshrined in the 1992 Fourth Republican Constitution (Chapter 20), the 1993 Local Government Act (Act 462), and the 2010 Local Government Service Act 936. The Constitution recognizes decentralization as one of the keys to realizing the ideals of democracy, including government accountability and responsiveness, and lays down the legal regime for its implementation.

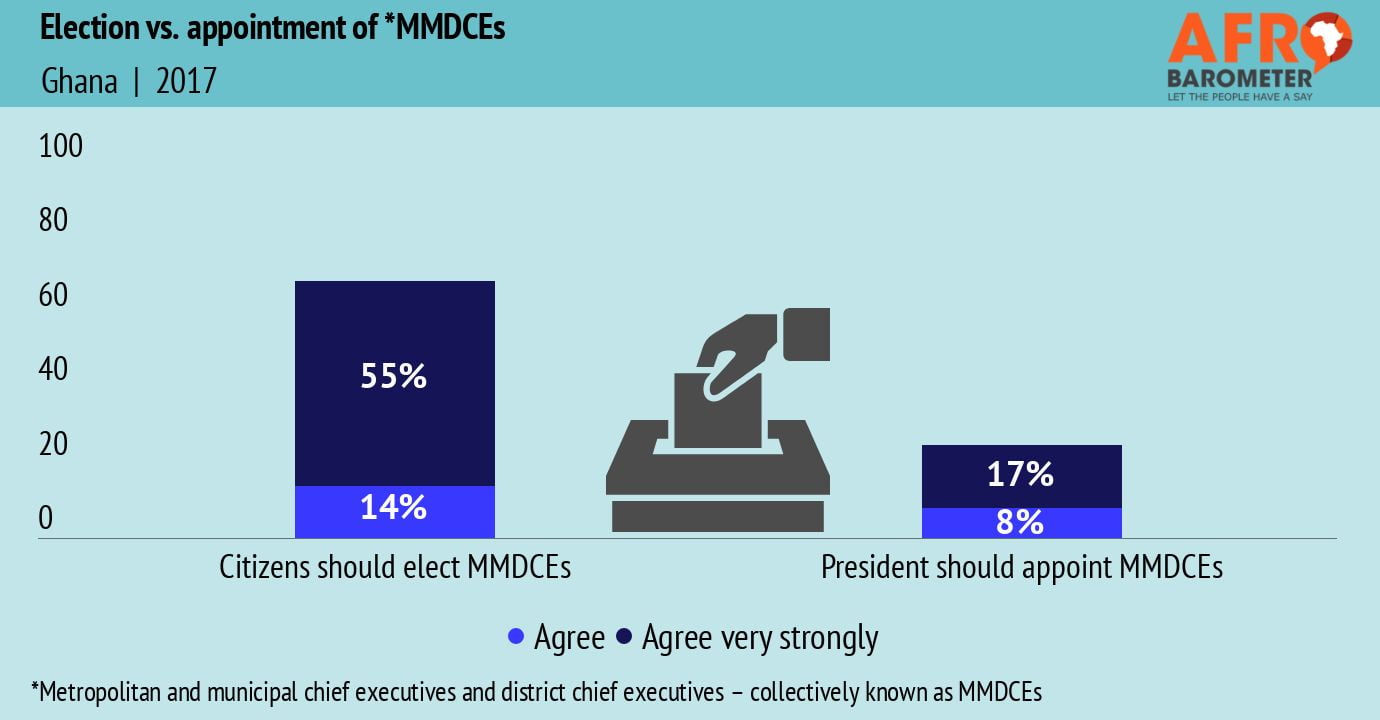

Even so, the Constitution vests enormous political power in the president by assigning him the responsibility of appointing all mayors (metropolitan and municipal chief executives) and district chief executives – collectively known as MMDCEs – as well as one-third of local councillors who serve alongside the two-thirds elected to metropolitan, municipal, and district assemblies (MMDAs).

In practice, this arrangement has allowed the ruling political party to foist political appointees on a supposed non-partisan structure, which according to the Government of Ghana Decentralisation Policy Review (2007) has helped make many MMDCEs subservient and accountable to the appointing authority while weakening accountability to the citizens they are supposed to serve.

Despite many campaign pledges by political parties and candidates – especially when they are in the opposition – to make MMDCE positions elective, successive governments, once in power, have not shown the political will to give up this mechanism for dispensing political patronage.

Even when the 2010 Constitution Review Commission (CRC) recommended amending the Constitution to make MMDCE positions elective, the government issued a white paper aimed at maintaining presidential patronage by allowing him to nominate five MMDCE candidates who would then be vetted by the Public Services Commission for competence before three of them would be presented for popular election (Government of Ghana, 2012).

During and since his 2016 election campaign, President Nana Akufo-Addo has consistently promised to make MMDCE positions elective, even suggesting that the current set of MMDCEs will be the last batch of appointed chief executives (Ghana News, 2017; Business Ghana, 2016; Otec FM, 2018).

This paper uses data from the 2017 Afrobarometer survey in Ghana to explore three questions and discuss related policy considerations:

1. Are Ghanaians supportive of the call to make MMDCE positions elective?

2. What are factors that drive support for or opposition to elective MMDCEs?

3. If Ghanaians support the call for election of MMDCEs, do they recommend partisan or non-partisan elections?

Related content