In contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, where many countries experienced political liberalization during the late 1980s and early 1990s (Bratton, 1997), the authoritarian regimes of North Africa were largely able to resist popular demands for transformation by introducing limited, topdown reforms. In Tunisia, there were some improvements to political freedoms after Zine El Abidine Ben Ali took office in 1988 and was elected as president the following year in the country’s first election since 1972 (Abushouk, 2016). This brief period of loosened restrictions was followed, however, by decades of authoritarian repression: “Even in a region that was notorious for its leaders’ disdain for honest government and civil liberties, Tunisia [under Ben Ali] long stood out for the thoroughness of its system of control and repression” (Freedom House, 2012, p. 4).

Optimism about the prospects for democratization in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region emerged in 2011 in response to a series of mass anti-government protests known as the Arab Spring. The events led to the overthrow of four authoritarian regimes in rapid succession that year, including Ben Ali’s, but it was soon evident that most regimes would ultimately prove resistant to these demands for reform (Freedom House, 2012). The protest movements have resulted in divergent outcomes, from a full democratic transition in Tunisia to ongoing civil conflicts in Libya and Syria.

Although widely considered to be the only unqualified success story of these uprisings, Tunisia’s progress has been accompanied by periods of severe political upheaval and insecurity. In recent years, the country has experienced a number of high-profile attacks on security forces and civilians and has become a leading source of recruits to extremist organisations such as the Islamic State (IS) (Soufan Group, 2015; Dodwell, Milton, & Rassler, 2016). Growing numbers of ex-combatants from foreign conflicts return to an absence of a government program for their de-radicalization and reintegration into Tunisian society (Gall, 2017). The current security context has sparked fears of damage to the country’s prospects for further democratization.

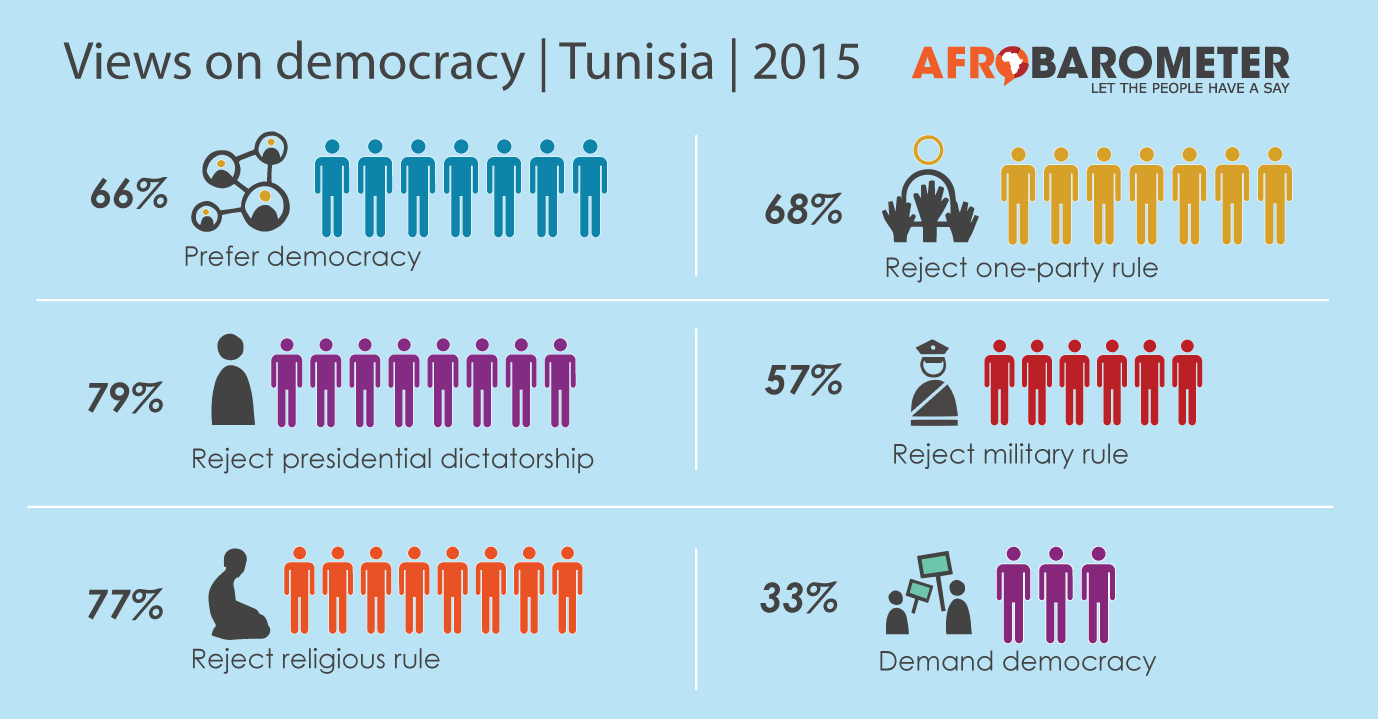

This paper examines Afrobarometer public opinion data to assess the extent to which citizens have embraced political changes since 2011. Do Tunisians perceive an improvement to the country and the North Africa region since the events of the Arab Spring? Are they supportive of democracy and the way it is being implemented? What role do they think religion should play in the country’s democracy? Do they believe that the government should prioritize further democratization over national security concerns?

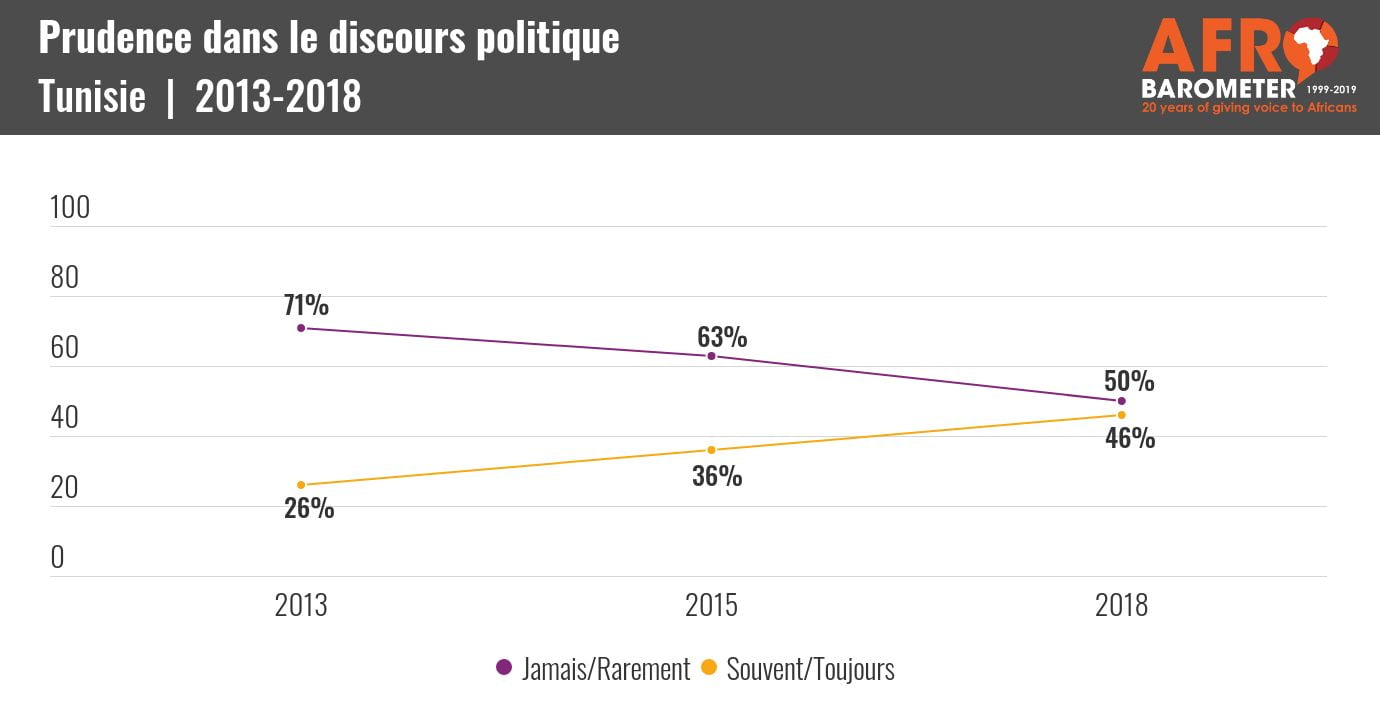

Results show that Tunisians are divided: Only a slight majority say the Arab Spring has had a positive impact on the country. This ambivalence may be explained by dissatisfaction with progress in some policy areas, including corruption and socioeconomic and security outcomes. Public demand for democracy and satisfaction with its implementation have increased. However, there is evidence that the country’s security context could threaten gains toward consolidating citizen support for democracy.

Related content