- A majority of Mauritians express “just a little” trust or “no trust at all” in key political institutions and leaders, including the president (59%), the prime minister (54%), the National Assembly (57%), municipal/district councils (57%), and both ruling (56%) and opposition (58%) parties. o Even the judiciary is trusted “just a little” or “not at all” by almost half (48%) of respondents.

- More than seven in 10 citizens (72%) say the level of corruption in the country increased “somewhat” or “a lot” over the past year.

- Almost three in 10 respondents say “most” or “all” officials in the prime minister’s office (29%) and members of the National Assembly (28%) are corrupt, while large majorities see at least “some” corruption among all key public institutions and leaders the survey asked about.

- Nearly three-quarters (72%) of citizens believe that people who report acts of corruption to the authorities are at risk of retaliation or other negative consequences.

- Citizens offer mixed assessments of the job performance of their elected leaders, including their municipal or district councillor (50% approval), the prime minister (47%), and their National Assembly representative (42%). o Only 31% give President Prithvirajsing Roopun a passing mark.

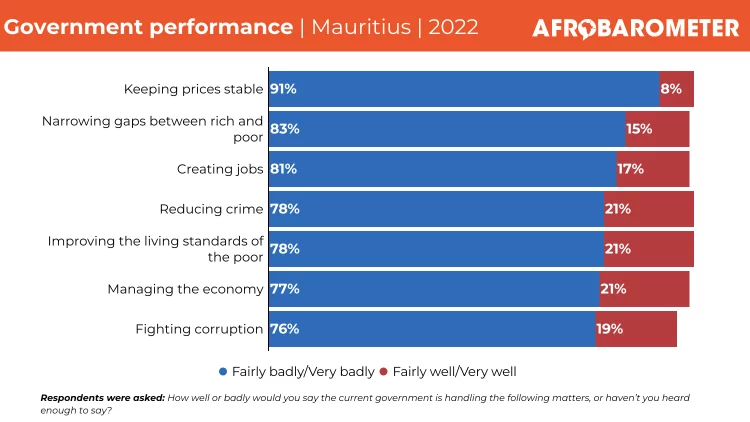

- Large majorities say the government is doing “fairly badly” or “very badly” at keeping prices stable (91%), narrowing gaps between rich and poor (83%), and creating jobs (81%).

Home to a population of just 1.25 million, the Republic of Mauritius has long prided itself on the stability of its multiparty parliamentary democracy, its good governance, and its “economic miracle” transforming a low-income, agriculture based economy into an economic powerhouse (Tan, 2023; Africanews, 2019; World Bank, 2022).

But cracks have appeared in recent years in the sheen of its reputation for good governance and economic development (Darga & Peeraullee, 2021; Financial Times, 2022).

After the 2019 general election – in which the Militant Socialist Movement (MSM) emerged victorious, confirming Pravind Jugnauth as prime minister – opposition candidates challenged the validity of the results, and Mauritians’ confidence in the quality of their elections weakened (African Arguments, 2021; Darga, 2021).

Over the past two years, discontented Mauritians have repeatedly taken to the streets to protest rising food and fuel prices and government corruption (Moonien, 2022; Africanews, 2021, 2022; Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022).

And even as the Democracy Index placed Mauritius among the world’s 20 most democratic countries (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021), the V-Dem Institute (2022) cited it as one of the 10 most rapidly “autocratizing” countries.

Critics have accused the prime minister of undermining democratic practices, including evading questions about corruption scandals in which he may be implicated (allAfrica, 2020; Institute for Security Studies, 2018). Several other leaders have also been embroiled in corruption scandals, including former President Ameenah Gurib-Fakim, who resigned after allegations that she had misused a Planet Earth Institute credit card to buy personal luxury items (Al Jazeera, 2018).

In 2020, the European Union placed Mauritius on a blacklist for money laundering and terrorism financing, though this was reversed in early 2022 (Axis, 2022). Another blow arrived with the African Development Bank’s revelation of procurement corruption in a large energy project (Institute for Security Studies, 2020).

Against this backdrop, how do Mauritians’ see their public institutions and leaders?

Findings from the most recent Afrobarometer survey show that Mauritians express low levels of trust in public institutions and in their elected leaders. Most citizens say corruption has increased and indicate that ordinary people risk retaliation or other negative consequences if they report it.

Fewer than half of Mauritians approve of the way the prime minister, president, and National Assembly members have done their jobs. Overwhelmingly, Mauritians say the government is performing poorly at keeping prices stable, narrowing income gaps, and creating jobs.

Related content