- Support for restrictions on media and associational life is highly situational. While people are broadly supportive of limits to hate speech, false information, and calls to violence, this does not necessarily mean they want to give governments broad discretion to limit civic freedoms more generally.

- Those who support limits to civic spaces are not just following leaders’ arguments. Africans have their own complex feelings about civic spaces; a call by a president is not enough on its own to drive public sentiment significantly.

- Polarization is inimical to civic freedoms. As government supporters trust their own group more and the opposition less, they are more open to limiting civic spaces, possibly to squelch opponents.

- People do not necessarily see limits to civic spaces, such as censorship of hate speech and misinformation, as anti-democratic. Rather, they might see it as essential to protect liberal democracy.

Civic freedoms, including freedom of the press and of association, are central to liberal democracy. However, publics are often divided in their support for such freedoms, particularly when they see rights to share messages and organize as causing potential harms to society. Further, politicians often stoke or take advantage of such fears to squelch potential challenges.

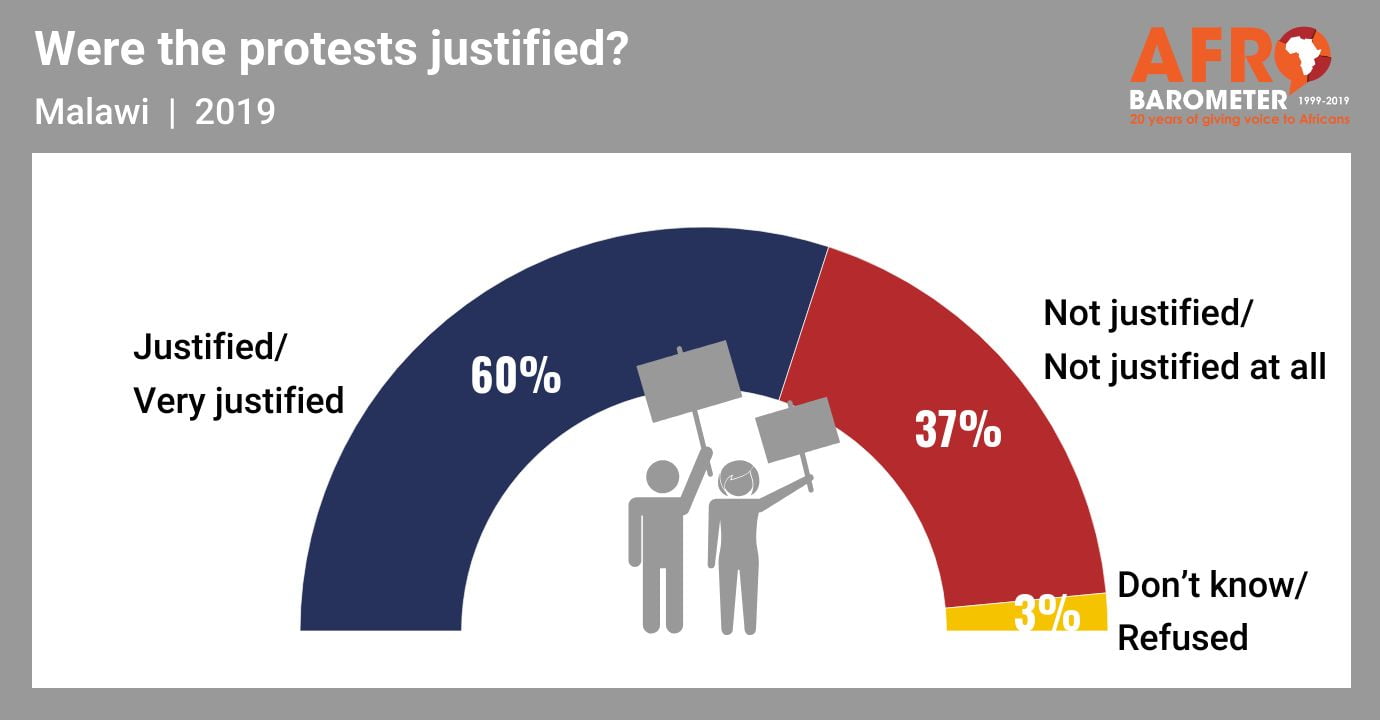

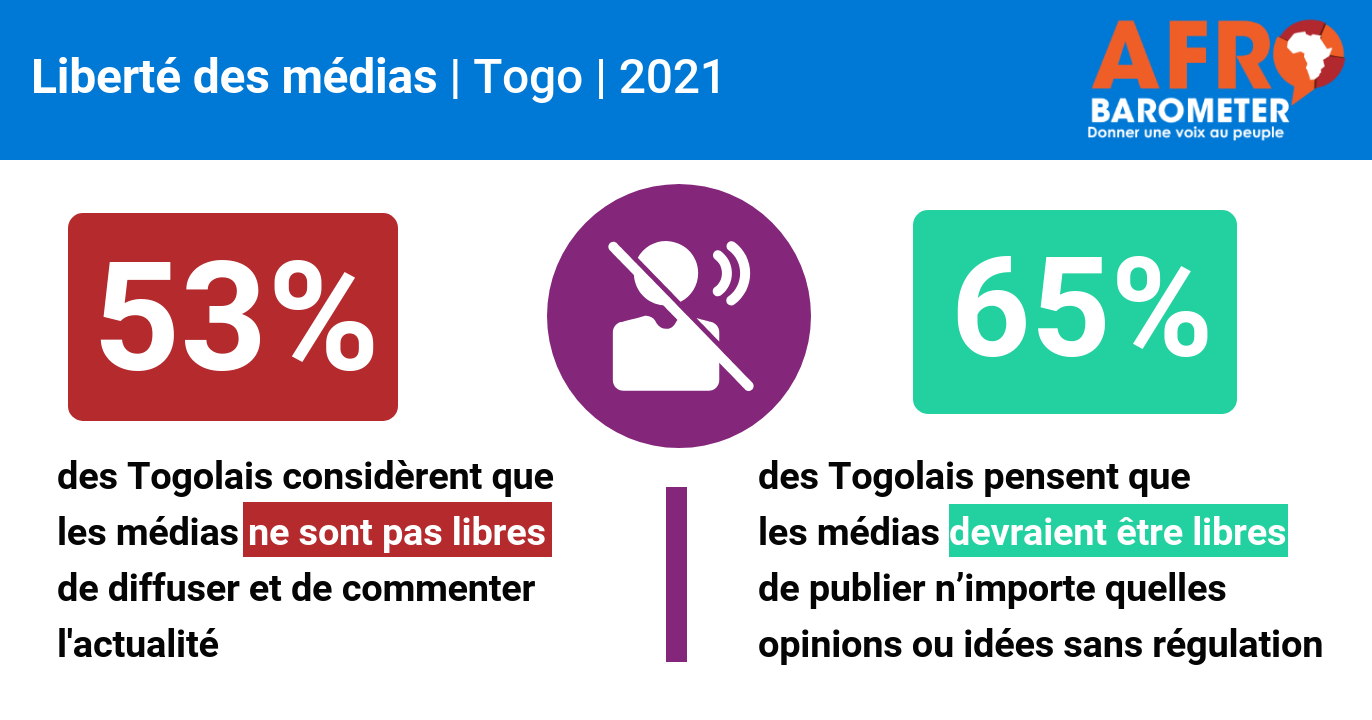

Recent Afrobarometer surveys have shown worrying trends in this area, with significant declines over the past decade in popular support for freedoms to join organizations and for media to operate. The Confronting Threats to Civic Spaces project is intended to determine the underpinnings of support for freedoms of association and the media on the African continent.

What explains why some Africans are more supportive of civic freedoms than others? This project begins with hypotheses, developed from reviews of existing literature and interviews with African experts working in these areas. We group these nine hypotheses into three families: perceived threats to order, the public good, and national sovereignty; partisanship and polarization; and concerns about democracy.

We test these hypotheses with data from a variety of existing and original sources, both large-N and small-N and observational and experimental. Sources include Round 8 Afrobarometer data from 34 countries; special phone surveys, with an embedded conjoint survey experiment, in four countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda); focus group discussions in those four countries; and an online survey of media experts (Nigeria).

Related content