As featured on the Democracy in Africa site.

COVID-19 is already having a devastating impact on the continent’s most vulnerable populations. While most African societies enjoy key assets they can rally to the response, many governments face trust deficits and have poor track records of providing for the economic and social welfare of their citizens. Mismanaging their response to COVID-19 through coercive measures and draconian enforcement could further undermine their political legitimacy and widen the divide between citizens and their governments.

The rule of law vs. reality

Data collected from more than 45,800 respondents across 34 African countries during Afrobarometer Round 7 (2016/2018) reveals that Africans generally regard their states as legitimate. More than three-quarters (78 percent) say that people must always obey the law, including majorities in all 34 countries. In short, it’s likely that the public is generally disposed toward complying with the wave of restrictive new legislation and decrees promulgated in the face of COVID-19.

Citizens may be especially willing to tolerate restrictions, at least temporarily, to protect their health and security. When Afrobarometer asked respondents about their willingness to tolerate limits on freedom of movement when public security is threatened, majorities endorsed the trade-off.

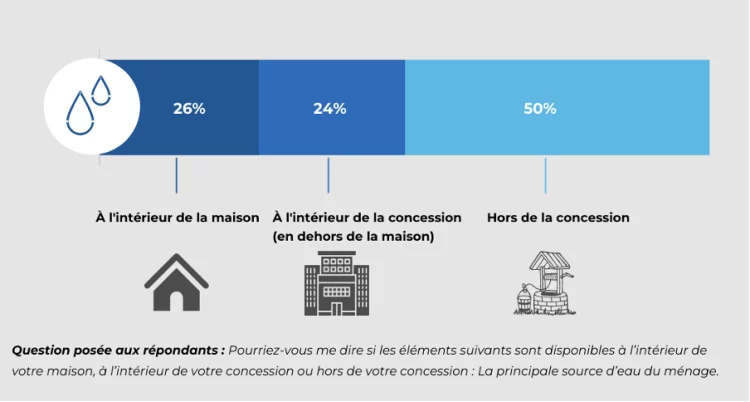

Yet hundreds of millions confront limited household reserves of money, food, and water, and thus lack the economic resilience to navigate a sustained lockdown. For these citizens, the new restrictions can mean a choice between compliance and survival. As essential as lockdowns have proven to be for flattening the curve of the pandemic, simply demanding that people stay home is not a viable option for many of Africa’s most vulnerable.

The record of government performance in securing citizens’ basic needs prior to the current crisis is not especially reassuring. Only 52 percent of Africans say their governments are doing fairly or very well in improving basic health services. Nearly four in 10 (38 percent) report that they or someone in their family had to go without medical care in the past year. Just 44 percent rate their governments’ provision of clean water and sanitation positively, and fewer than one-third say government efforts to improve living standards for the poor (31 percent) and ensure food security (32 percent) are effective.

The choice: compassion vs. coercion

The question is whether African governments will recognize these challenges, and respond in ways that demonstrate compassion and respect for their citizens, or instead act coercively against them. Civic activists are urging governments to avoid one-size-fits-all decrees and instead work with communities to develop flexible and realistic responses. So far, the record is mixed. Ghana, South Africa, and many other countries have worked to strengthen safety nets by waiving utility bills, offering wage subsidies and food programs, and increasing social-welfare grants. At the same time, security forces in some countries have beaten, arrested, and even shot citizens for violating lockdown orders.

Unfortunately, it is not always clear that governments have the legitimacy needed to engage communities in conversations about more effective responses. Elected leaders face a trust deficit: Fewer than half (46 percent) of citizens trust them when we average trust in the president (52 percent), Parliament (43 percent), and local government council (43 percent) (Figure 1). Trust in informal leaders – especially traditional and religious leaders (trusted by 57 percent and 69 percent, respectively) – is much stronger. These informal leaders could be key assets that governments can call on. Unfortunately, governments have seemed more inclined to turn to their security forces for their messaging.

Figure 1: Popular trust in officials | 34 African countries* | 2016/2018

Respondents were asked: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? ( percent who said “somewhat” or “a lot”) (*Note: The question on traditional leaders was not asked in Cabo Verde, Mauritius, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe.)

Political leaders may see trust in their militaries as a resource they can deploy in their coronavirus responses. Trusted by 64 percent, Africa’s armies score second only to religious leaders, and enjoy substantially more trust than presidents (+12 percentage points) (Figure 2) or parliaments and local government councils (+21 points each).

Figure 2: Trust in president and military (percent) | 34 African countries | 2016/2018

Respondents were asked: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? ( percent who said “somewhat” or “a lot”)

But as security forces in Nigeria, Kenya, Mauritius, South Africa, Uganda, and elsewhere face accusations of using excessive force while imposing lockdowns, the public’s confidence in their militaries may be more complicated than it first appears. Across 34 countries, only 53 percent say the military usually “operates in a professional manner and respects the rights of citizens.”

Accountability or avarice?

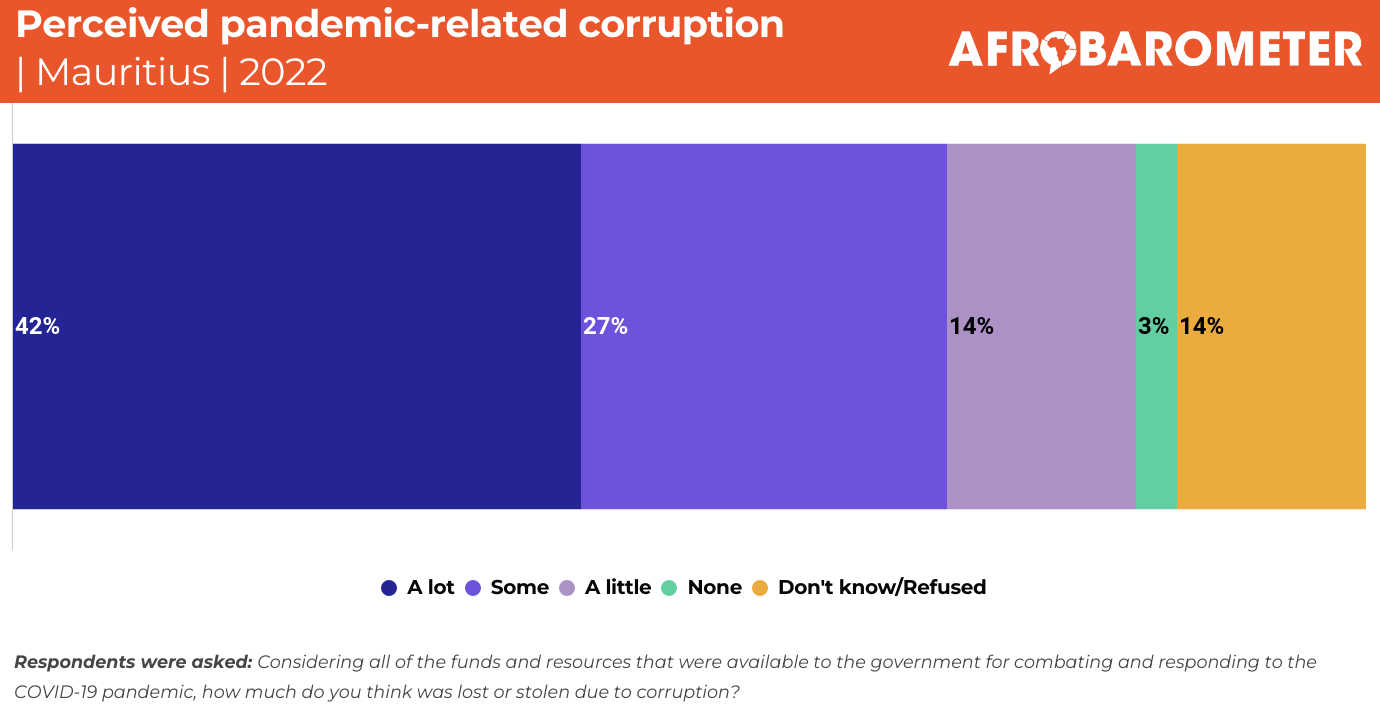

One of the lessons learned in Africa’s Ebola crises is the power of corruption to undermine trust and destroy legitimacy. Ebola responses have had to overcome perceptions that the disease was a manufactured scam on the part of corrupt officials as well as reports that even desperately ill patients were forced to pay bribes to get treatment.

As the continent grapples with coronavirus, the lack of trust and legitimacy engendered by widespread corruption may undermine some governments’ efforts to respond. Across 34 countries, nearly four in 10 respondents (38 percent) report believing that “most” or “all” government officials are corrupt. And among those who sought care at public clinics or hospitals in the previous year, 13 percent report having to pay a bribe, a figure that soars to more than four in 10 in Liberia (43 percent) and Sierra Leone (50 percent) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Paid a bribe to get health care (percent) | 34 African countries | 2016/2018

Respondents who had contact with public health-care facilities during the previous 12 months were asked: And how often, if ever, did you have to pay a bribe, give a gift, or do a favour for a health worker or clinic or hospital staff in order to get the medical care you needed? ( percent who said “once or twice,” “a few times,” or “often”)

The likely influx of resources to combat the pandemic will present its own problems. Crises offer unscrupulous officials a multitude of opportunities for diversion, price-fixing, and other forms of corruption that will not be lost on the ordinary citizens who will pay the price.

Building a legacy for legitimacy

But history does not have to be destiny. Even governments that start from a place of weakness have the opportunity to use their response to the coronavirus crisis to build their legitimacy, rather than further squander it. Grounding responses in compassion and empathy rather than coercion, and acting with transparency and accountability rather than self-dealing, could build trust and produce lasting benefits for their popular standing.

Related content