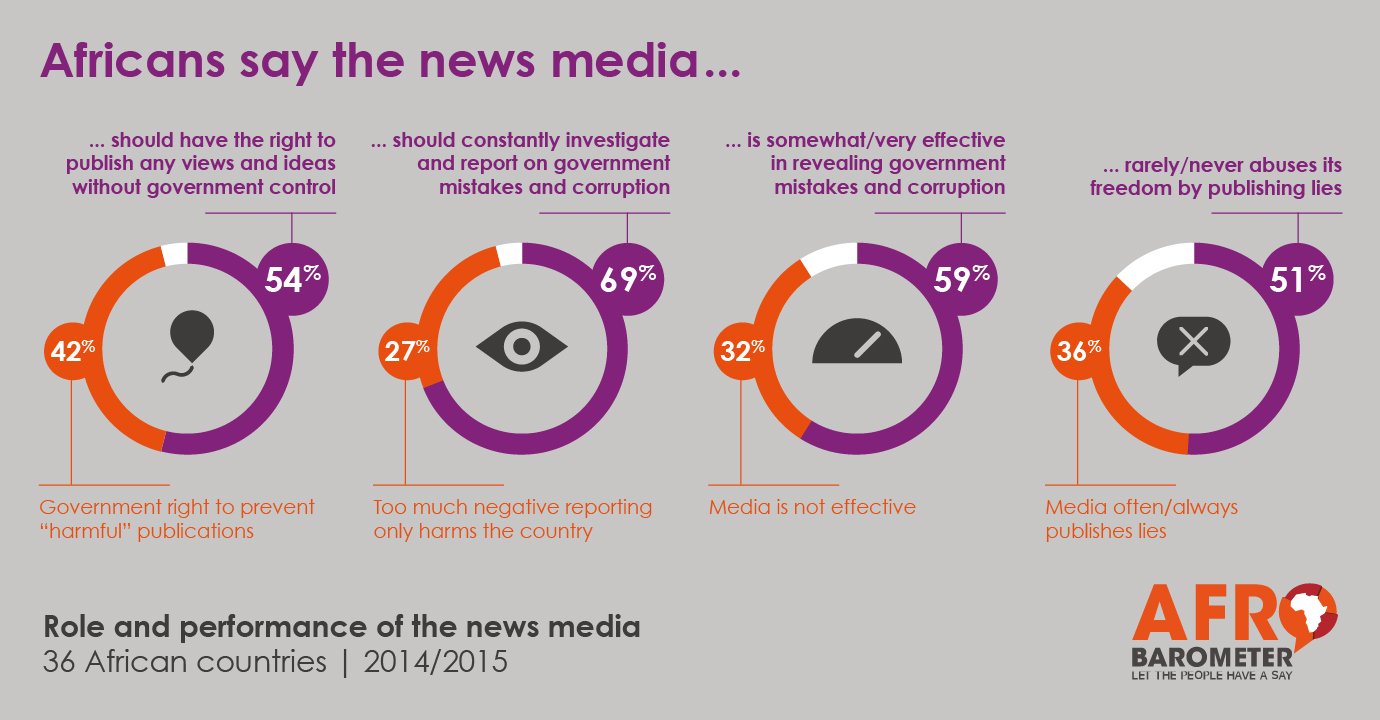

- More than two-thirds (69%) of Africans say the news media should “constantly investigate and report on government mistakes and corruption.” This is the majority view in every surveyed country except Egypt (where 46% agree).

- A majority (59%) of respondents say the news media is “somewhat” or “very effective” in revealing government mistakes and corruption. Across 34 countries tracked since 2011/2013, the proportion of citizens who say the media is “not very effective” or “not at all effective” increased from 26% in 2011/2013 to 30%.

- A slim majority (51%) say the media “rarely” or “never” abuses its freedom by publishing lies, but more than one-third (36%) of Africans – and in some countries more than two-thirds – say it does so “often” or “always.”

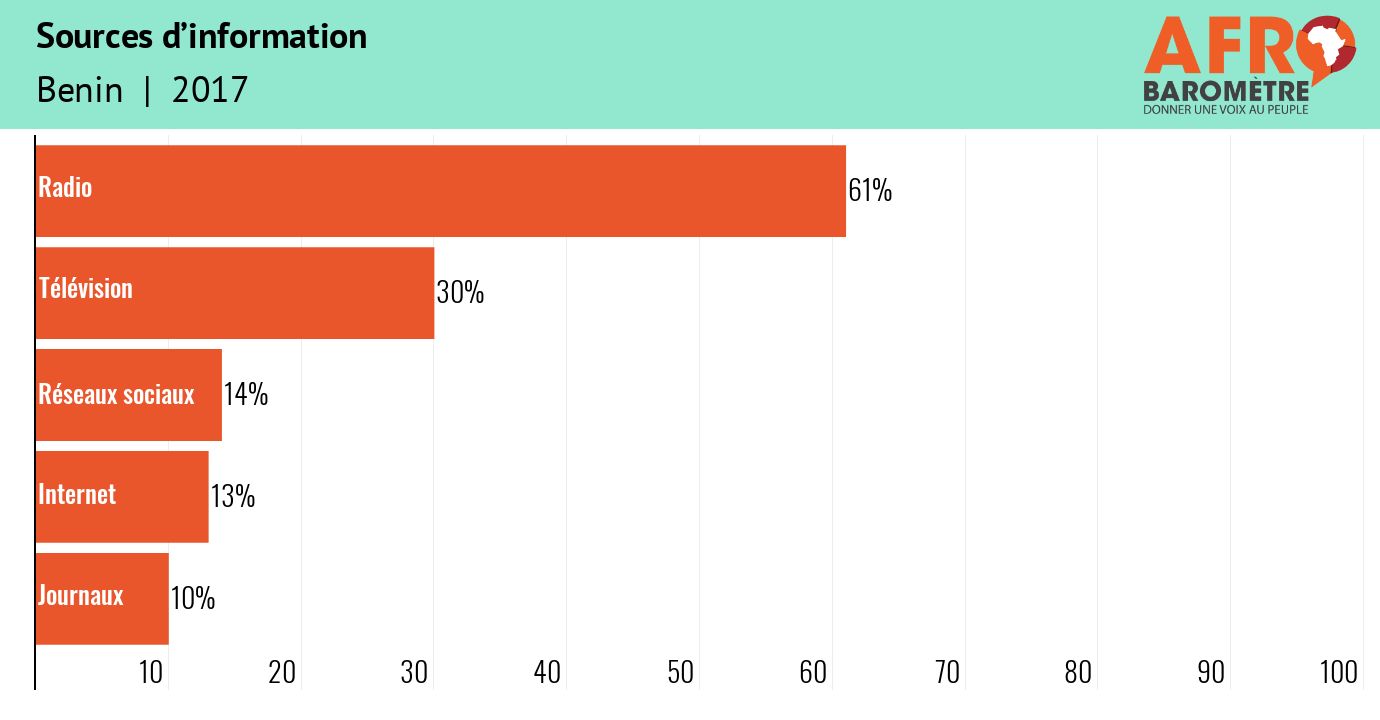

- Radio remains the most common news source, accessed by seven in 10 Africans either daily (47%) or “a few times a week” (22%). But radio and newspapers are slowly losing ground, while TV and the Internet are gaining. One in five Africans (21%) now regularly get news from social media such as Facebook and Twitter, and among youth and citizens with post-secondary education,

- In addition to using the media to get news, some Africans use it to express their opinions: About one in nine respondents (11%) say they contacted the media in the previous year to express their dissatisfaction with government performance.

More than 100 journalists have fled tiny Burundi to escape repression and danger, according to Reporters Without Borders – a dramatic illustration of the impact of a “deep and disturbing decline in respect for media freedom at both the global and regional levels” (Reporters Without Borders, 2016).

If a free press is a pillar of a free society, Africa marks World Press Freedom Day 2016 (May 3) amid growing concerns that this pillar is under attack by governments determined to silence critics. Free-press champions report growing numbers of journalists who have been harassed, intimidated, arrested, tortured, or exiled (Media Foundation for West Africa, 2015a, 2015b; Amnesty International, 2016). Freedom House (2016) says global press freedom has “declined to its lowest point in 12 years.” Some states have enacted repressive laws to censor journalists, often citing as justification a need to fight violent extremism (Egypt, Ethiopia, and Kenya) or to stop publication of “false, deceptive, misleading, or inaccurate information” (Tanzania) (CIPESA, 2015, p. 5) that could undermine “national unity, public order and security, morality, and good conduct” (Burundi) (International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law, 2015, p. 13). Beyond government repression, threats to media freedom come from violent non-state actors (such as extremist groups in Nigeria and Mali), influence-wielding officials, and even self-censoring journalists (Cheeseman, 2016). The net effect is to erode journalistic independence and muzzle the media “watchdogs” that are supposed to help ensure government accountability (Freedom House, 2015a).

These attacks on media freedom can also be seen as part of broader attempts to restrict space for civic activism. For instance, Tanzania’s and Nigeria’s cybercrime acts of 2015 have been criticized for disregarding issues of freedom of expression, granting excessive powers to the police, and affording only limited protections to ordinary citizens (Article 19, 2015; Sahara Reporters, 2015). Most recently, Uganda temporarily shut down social media and slowed the Internet during its presidential elections in February 2016, ostensibly for security reasons “to stop so many (social media users from) getting in trouble because some people use those pathways for telling lies” (BBC News, 2016). This trend of using state power to limit civic space has also been criticized in Burundi, the Republic of Congo, Egypt, Sudan, the Central African Republic, Niger, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Association for Progressive Communications, 2016).

If a media under attack needs public support at its back to safeguard its independence, Africa’s citizens offer such support – up to a point. In Afrobarometer’s latest surveys in 36 African countries, a majority (54%) of citizens say they support an independent media free from government interference. But this support varies significantly by country, and has weakened slightly since 2011/2013. And it leaves a robust four in 10 (42%) who believe that a government “should have the right to prevent the media from publishing things that it considers harmful to society.”