- Fully half (51%) of Ugandans see the costs of natural resource extraction, such as environmental pollution, as outweighing its benefits, such as jobs and revenues. Only 41% value the benefits more highly than the costs.

- A majority (56%) of citizens say that communities do not receive a fair share of resource extraction revenues, while only 35% think they do.

- Fewer than half (44%) of Ugandans think ordinary citizens have a voice in decisions about natural resource extraction near their communities.

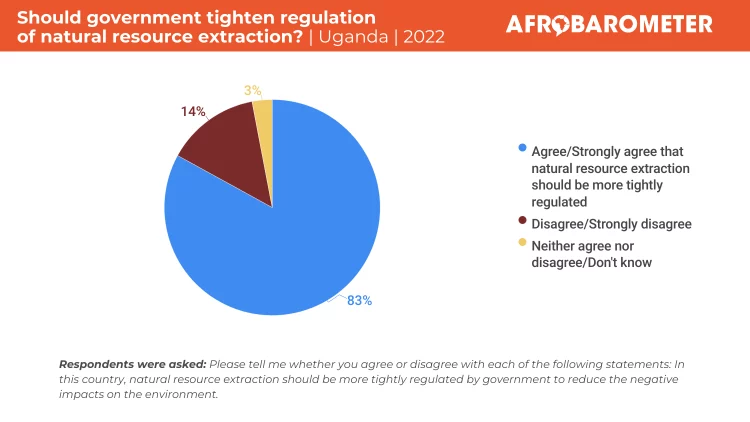

- More than eight in 10 citizens (83%) want the government to regulate natural resource extraction more tightly to reduce its negative impacts on the environment.

- More than two-thirds (68%) of respondents say corruption in the country increased during the year preceding the survey. The proportion who believe that graft increased “a lot” rose by 18 percentage points between 2019 (40%) and 2022 (58%).

- Eight in 10 citizens (80%) say the government is performing poorly in its fight against corruption. Dissatisfaction with government efforts to reduce corruption has grown significantly since 2005 (52%).

Although Uganda’s mining industry is small, accounting for only 2.3% of gross domestic product, it is projected to grow dramatically as a result of recent oil discoveries (Oketch, 2021). Oil production is expected to start by 2025, and the World Bank estimates that Uganda could earn up to U.S. $3 billion (about Shs. 11.4 trillion) per year from oil exports of up to 60,000 barrels per day at peak commercial production (Musisi, 2022).

This presents a unique opportunity for the country to usher in a new phase of economic growth and development – if it can escape the “resource curse.”

In other oil-rich countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as Nigeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Congo, and Gabon, oil wealth has often benefited only a few in or close to state power, without trickling down to the pockets of the poor (Bello, 2017; Mohammed, 2021).

Since initial oil-extraction activities in Western Uganda’s districts of Buliisa and Hoima got underway, many residents in affected communities have complained of meagre compensation for their land, forceful evictions, and a lack of transparency, accountability, and local employment from the oil companies. Land disputes have intensified in the area, and many locals have lost their traditional livelihoods in agriculture (Taylor, 2020; Ssekika, 2011; Onyango, 2021).

The planned construction of a 1,443 km oil pipeline, which is supposed to transport crude oil from Western Uganda to the Tanzanian coast, has sparked controversy as well. Last year, the European Parliament passed a non-binding resolution that seeks to delay development of the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline in the two countries, citing environmental and human-rights concerns (Independent, 2022). Oxfam (2020) estimates that about 14,000 households will lose land and hundreds will have to be resettled to make way for the pipeline.

Another cause for worry is Uganda’s rampant corruption (Kakumba, 2021). Will the oil project open new avenues for corruption to flourish?

According to the most recent Afrobarometer survey, Ugandans cast a critical eye on their natural resource extraction industry, with half seeing its costs as outweighing its benefits. Fewer than half think local communities have a voice in decisions about natural resource extraction or receive a fair share of the revenues, and a majority want the government to regulate the industry more tightly to protect the environment.

In addition, a majority of Ugandans think that corruption is getting worse in their country and that their government is doing a poor job of fighting it.