- About six in 10 citizens say they felt unsafe while walking in their neighbourhood (62%) and feared crime in their home (59%) at least once during the previous year. Experiences of insecurity have increased sharply over the past two years. Poor citizens are more than twice as likely to feel unsafe and to fear crime as their well-off counterparts.

- Two in 10 respondents (20%) say they requested police assistance during the previous year. Three times as many (63%) say they encountered the police in other situations, such as at checkpoints, during identity checks or traffic stops, or during an investigation.

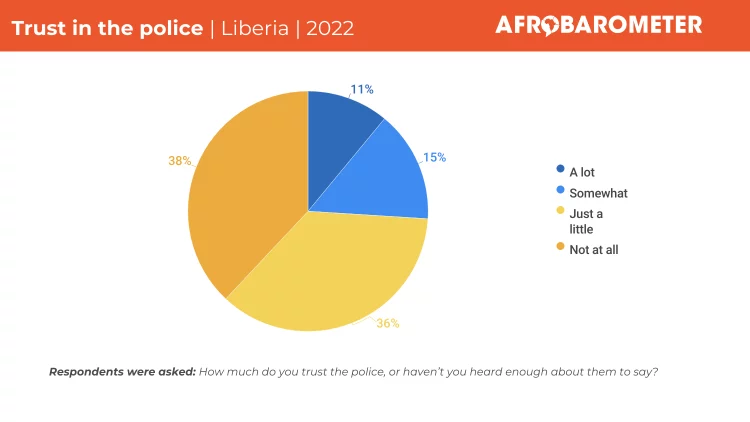

- Two-thirds (66%) of citizens say that “most” or “all” police are corrupt – the worst rating among 12 institutions and leaders the survey asked about.

- Only one-fourth (26%) of Liberians say they trust the police “somewhat” or “a lot.”

- Substantial proportions of the population say the police “often” or “always” stop drivers without good reason (53%), use excessive force during protests (39%) and with suspected criminals (38%), and engage in criminal activities themselves (35%).

After a civil war (1999-2003) in which it was factionalised and out of control, the Liberia National Police (LNP) was disbanded, then re-created with the support of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL), which assumed primary responsibility for internal peace and security for more than a decade (Centre for Public Impact, 2016; Human Rights Watch, 2013).

With the departure of UNMIL in 2018, the Liberian government resumed full responsibility for providing the necessary financial and logistical support for the LNP to maintain law and order in the country. But with competing national needs and priorities, this support has fallen short, leaving the police badly understaffed – with about 4,500 officers, far fewer than the 8,000 that UNMIL said were needed – and susceptible to unethical and unprofessional behaviour, including extortion and corruption. In his speech at the 2022 Carl Gershman Democracy Lecture Forum, U.S. Ambassador Michael McCarthy blamed inadequate government funding for breeding police corruption but also noted cases in which police officers have to ask the families of rape victims for gas money in order to do their jobs (Mehnpaine, 2022).

This dispatch reports on a special survey module included in the Afrobarometer Round 9 (2021/2023) questionnaire to explore Africans’ experiences and assessments of police professionalism.

Survey findings show that a majority of Liberians think most police officers are corrupt. Among citizens who encountered the police during the previous year, a majority say it was difficult to obtain assistance, and more than three-fourths say they had to pay a bribe.

Many also complain of unprofessional conduct, saying the police often use excessive force, stop drivers without good reason, engage in criminal activities, and fail to respect citizens’ rights.

A growing number of Liberians report experiencing insecurity in their neighbourhoods and homes, and most say the government is doing a poor job of reducing crime.