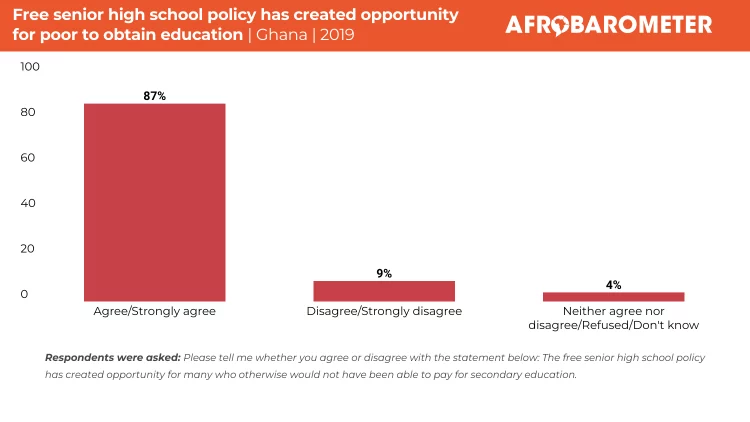

- In 2019, an overwhelming majority (87%) of Ghanaians said the free SHS policy created an opportunity for many students who otherwise would not have been able to pay for secondary education.

- Poorer citizens (76%) were less likely than their better-off counterparts (89%) to agree that the policy created an opportunity for many who otherwise would not have been able to afford a secondary education.

- Ghanaians were about evenly split on whether the policy should have targeted only the poor.

- Half (50%) of Ghanaians said it was better to have free senior high school even if it led to an increase in the number of educated citizens who cannot find a job.

- While half (50%) of respondents said the government should have put all the necessary structures in place before implementing the free school policy, 45% believed it was right to start implementation and address challenges as they arose.

- Positive ratings of the government’s performance in addressing educational needs have declined by 44 percentage points since 2017, from 82% to 38%.

Ghana’s Akufo-Addo administration began implementing a free senior high school (SHS) policy in September 2017, fulfilling a campaign promise in the 2016 general election. The policy, one of the country’s biggest welfare programmes, has been a significant push toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals target of free, publicly funded, inclusive, equitable, quality primary and secondary education (sdg4education2030, n.d.).

Senior high school enrolment levels increased by 17.2% in 2017 and by 30.7% in 2018 (Opoku Prempeh, 2018) as almost all students (97.1%) who qualified their basic education certificate examinations were placed into free secondary schools to continue their education. Government spending on education increased almost five-fold between 2017 and 2021(Government of Ghana, 2021). To accommodate the increased enrolment and address the stress on school infrastructure, the government adopted a double-track system that allows two separate cohorts of students in school at different times of the academic year.

While supporters describe the policy as bold and far-reaching (Modern Ghana, 2022), debate about its merits, implementation, impact on education quality, and financial sustainability continues.

The programme’s cost has left little fiscal space to fund educational infrastructure and materials, and heavy reliance on proceeds from Ghana’s oil sector leaves its funding subject to the uncertainties of the petroleum sector (UNICEF, n.d.; B&FT Online, 2022). Some experts have warned that the programme is not sustainable and should instead target only the poor, excluding students whose families can afford to pay their fees (Ghanaweb, 2017; Ghanaweb, 2022; MyJoyOnline.com, 2019).

While the government initially rejected calls for review (Graphic Online, 2020), financial strains exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic have compelled it to call for a broad stakeholder dialogue on a possible review of the policy (Citinewsroom, 2022; MyJoyOnline.com, 2022). In light of this ongoing discourse, Afrobarometer survey findings from 2019, 2021, and 2022 offer insights into public opinion on the free SHS policy.

Two years into implementation of the new policy, most Ghanaians saw it as creating an opportunity for many students who otherwise would not have been able to afford a secondary education. But citizens were sharply divided as to whether the policy should have targeted only the poor, whether free senior high school was good even if it increased the ranks of the educated unemployed, and whether implementation of the policy should have been delayed until all necessary structures were in place.

Overall, citizens ratings of the government’s performance on education have taken a nosedive since 2017.

Related content