- Only about one in seven South Africans (14%) said they contacted a traditional leader during the preceding year.

- Fewer than two in 10 citizens (18%) said traditional leaders “often” or “always” do their best to listen to what people have to say.

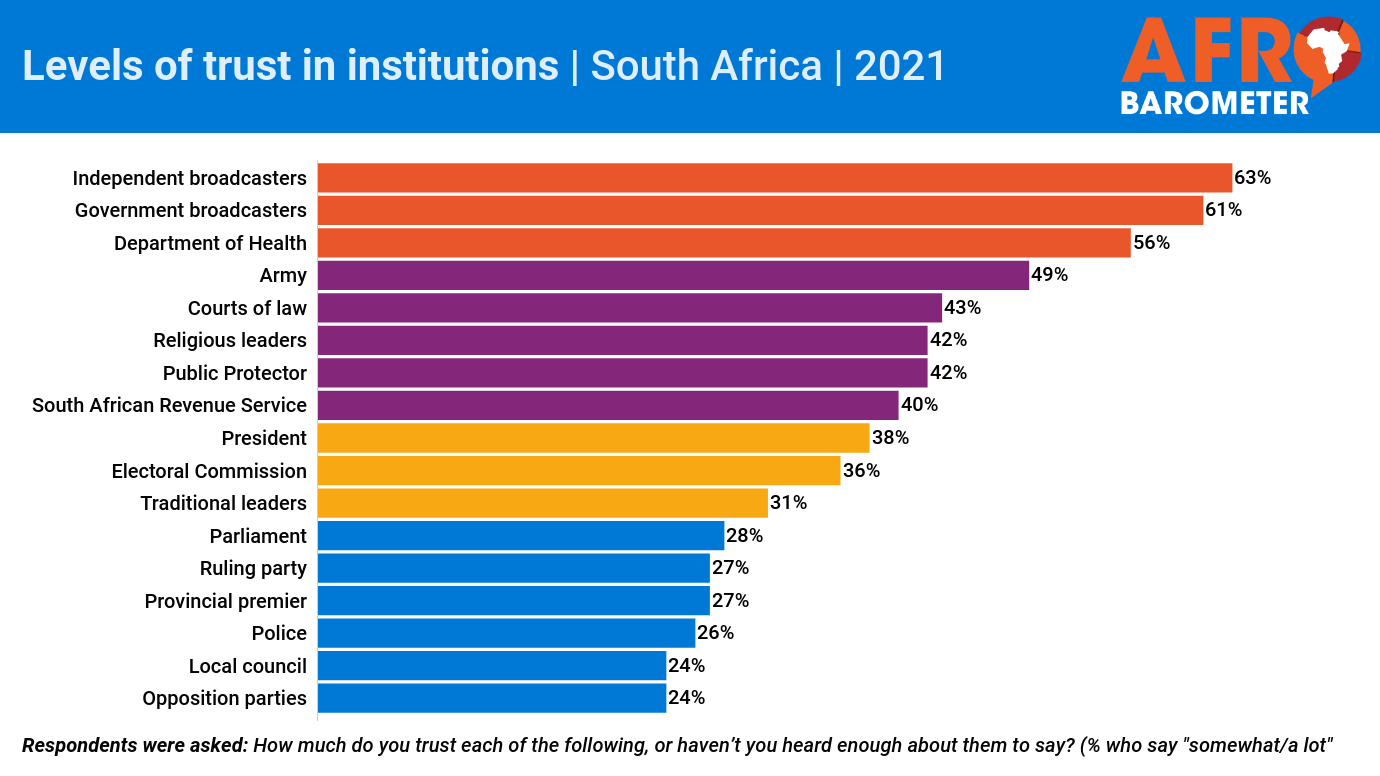

- Only three in 10 respondents (31%) said they trust traditional leaders “somewhat” or “a lot,” down from 44% in 2015. Four in 10 (41%) expressed little or no trust, while 27% said they “don’t know.”

- About one-third (35%) of citizens said “most” or “all” traditional leaders are involved in corruption.

- Only one in four South Africans (25%) approved of how their traditional leaders performed their jobs during the previous year.

In 2010, the South African government streamlined the number of officially recognised traditional kingdoms from 13 to seven to address issues created by the former apartheid and colonial governments (Government of South Africa, 2010). These kingdoms are subject to the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act 41 of 2003 and Chapter 12 of the Constitution of South Africa 1996.

Despite this legal framework, issues surrounding traditional leadership in South Africa are far from settled.

Since Parliament recognised several marginalised groups in the Traditional Khoi-San Leadership Act of 2019 (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2021), disputes have erupted over the leadership of the AmaMpondo, AmaXhosa, AmaZulu, BaPedi, VhaVhenda, and BaLobedu (Mkhwanazi, 2021). A major case before the KwaZulu- Natal High Court contests inheritance rights after the death of AmaZulu King Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu. When King Misuzulu kaZwelithini ascended to the throne in 2021, South Africans saw live footage of the Zulu royal family breaking out into a commotion that went as far as the High Court for arbitration (Makhaye, 2022; SABC, 2021).

In a blow to traditional leaders who had been collecting rents, the South African High Court recently declared that people living on customary land covering 30% of the province of KwaZulu-Natal, held in trust by the Zulu king, are the “true and beneficial owners” of that land. The judgment confirmed that the Ingonyama Trust Board, which was created before the 1994 elections, could not convert the customary land rights of occupiers to rent-paying leases as it has been doing over the past few years (Cousins, 2021; Harper, 2022).

In addition to infighting over positions and powers, traditional leaders have been the focus of politicians’ efforts to gain votes. Before the 2021 local government elections, the Economic Freedom Fighters party gifted the AbaThembu king a 1.8-million-rand car in the run-up to local government elections, and King Dalindyebo encouraged his people to vote for the EFF (SABC, 2021).

In this context, how do South Africans see the role of traditional leaders?

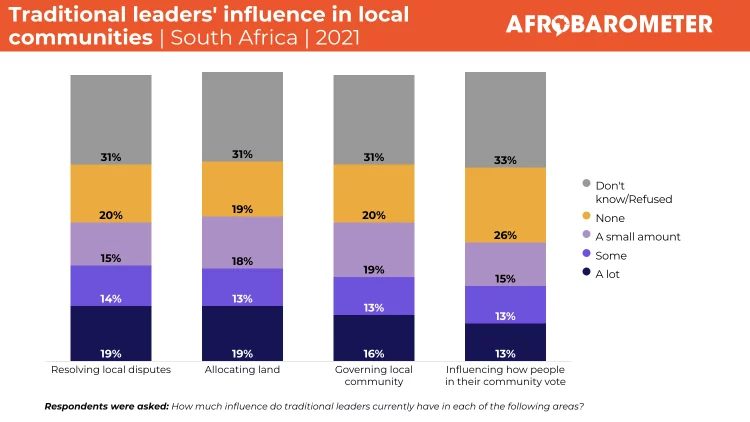

Findings from the most recent Afrobarometer survey show that many South Africans do not know much about traditional leaders. Relatively few citizens have contact with traditional leaders, think they listen to what people have to say, consider them influential and trustworthy, and give them positive ratings on their job performance. Only a quarter of South Africans think traditional leaders focus mainly on serving the interests of the people in their communities.