- More than seven in 10 Batswana prefer democracy over any other political system (72%) and say that in practice, the country is “a full democracy” or “a democracy with minor problems” (75%).

- Batswana overwhelmingly (93%) reject one-person rule without accountability through Parliament and elections.

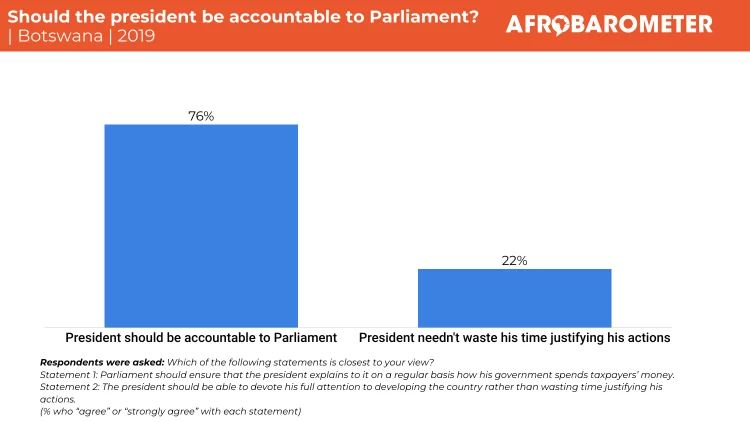

- Three-fourths (76%) of citizens say the president should be accountable to Parliament for how his government spends taxpayers’ money. An even greater majority (80%) say he must always obey the country’s laws and courts, even if he thinks they are wrong.

- In practice, 55% of Batswana say their president “never” ignores Parliament or the laws and courts.

Botswana is often described as an open and competitive democracy that over the years has unfailingly held transparent, credible, and peaceful elections (Sebudubudu, Osei- Hwedie, & Tsie, 2017). Its politics operate within the framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic and multiparty system that provides space for citizen participation and consultation, an independent and pluralistic media, effective parliamentary engagement, and independent oversight bodies (Kebonang & Kaboyakgosi, 2017). This framework has enabled the sharing of power through checks and balances and considerable public control over the use of public resources, making accountability a central piece of governance and reducing the risk of power abuse and corruption (Botlhale & Lotshwao, 2015).

In response to the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, President Mokgweetsi Masisi declared a state of emergency (Dinokopila, 2020). In addition to the extensive powers bestowed on the executive by Section 47 of the Constitution, the state of emergency granted the president unfettered powers to rule by decree, bypass the usual processes for awarding public tenders, and curtail civil liberties. This was the second state of emergency in Botswana’s history. The first, in September 1999, was declared by then-President Festus Mogae to correct an erroneous national voters roll that threatened to disenfranchise thousands of voters.

Botswana’s 2020 of state of emergency declaration, which lasted about 18 months, was not unique in the region; Lesotho and Namibia also declared states of emergency, while Malawi, Zimbabwe, Eswatini, and South Africa used existing laws on disaster management, civil protection, and public health to declare health emergencies (Gonese, Shivamba, & Meerkotter, 2020).

But opposition parties in Botswana vigorously opposed the emergency declaration, arguing that the Public Health Act was sufficient to deal with the situation and that the declaration – which they saw as an attempt by members of the ruling Botswana Democratic Party to enrich themselves through the award of tenders – would weaken accountability for the executive and curtail citizens’ civil liberties.

More broadly, scholars such as Rapeli and Saikkonen (2020) have raised concerns that emergency rule associated with the management of the COVID-19 pandemic may concentrate power in the executive in some democratic countries or exacerbate the autocratisation of countries where democracy is already eroding.

How do ordinary Batswana see the balance of power and accountability in their country?

Afrobarometer’s Round 8 survey (2019) shows that citizens overwhelmingly endorse democracy and reject one-person rule without accountability. Most insist that their president be accountable to Parliament and obey the country’s laws and courts, even if he thinks they are wrong.

Related content