- In Lesotho, men trail women in educational achievement, with less secondary schooling and a greater proportion who lack formal education altogether.

- Women and men are about equally likely to own a mobile phone, a radio, a television, a motor vehicle, and a computer, but more men than women report owning a bank account (42% vs. 37%).

- About eight in 10 Basotho (79%) say women should have the same rights as men to own and inherit land. A weaker majority (59%) – and only 48% of men – say women should have the same rights as men to get paying jobs.

- Almost three-fourths (73%) of Basotho say women should have the same chance as men of being elected to public office.

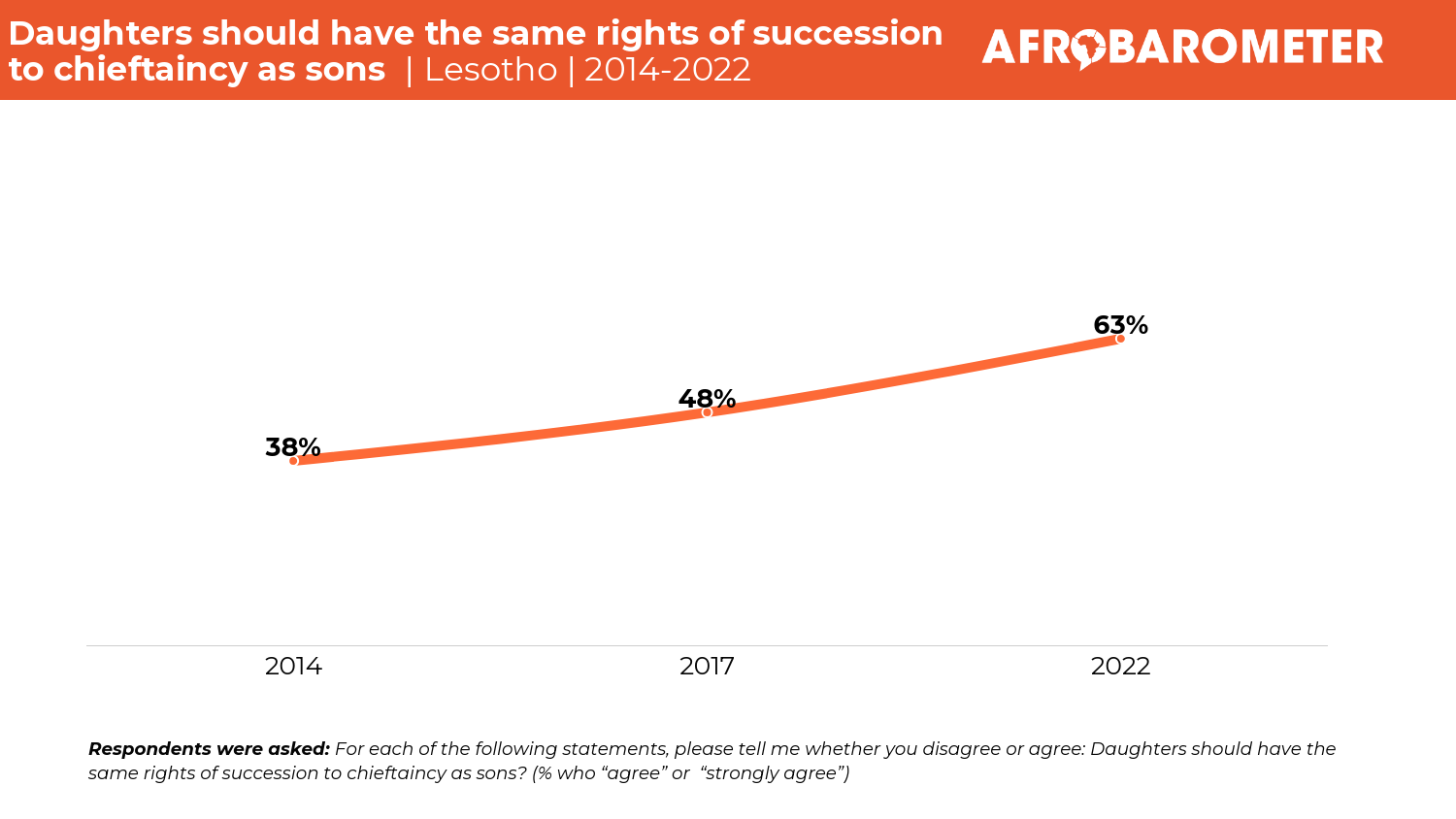

- Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Basotho – including a slim majority (53%) of men – say daughters should have the same rights of succession to chieftaincy as sons.

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal No. 5 calls for gender equality and empowerment of all women and girls, a cross-cutting principle underpinning inclusive development (United Nations, 2015). Globally, despite positive strides toward this goal, huge inequalities remain (UN Women, 2022).

Gender gaps are perhaps clearest in political leadership. A report from the World Economic Forum (2021) highlights the fact that across 156 countries, women hold only 26.1% of some 35,500 parliamentary seats and just 22.6% of more than 3, 400 ministerial posts. Eighty-one countries have never had a female head of state. At the current rate of progress, the World Economic Forum estimates that it will take a whopping 145.5 years to attain gender parity in politics.

In Lesotho, the government has made efforts to promote gender parity in politics by introducing electoral gender quotas (Nyane & Rakolobe, 2021). At the national level, the “zebra list” model requires political parties to submit candidate lists on which women alternate with men for the 40 proportional representation seats (out of 120 seats total) in the National Assembly. At the local level, a quota system requires at least 30% women’s representation on local councils (Government of Lesotho, 2011).

One area in which glaring gender inequality persists in Lesotho concerns succession to the chieftaincy: By a High Court ruling citing the Constitution, princesses are still denied the right to become chief (Lesotho Legal Information Institute, 2013).

On other fronts, the country has formulated national legislation and strategies to address gender gaps under its 2003 National Gender and Development Policy and its successor, the Gender and Development Policy 2018-2030 (Government of Lesotho, 2018). The legal framework includes the Legal Capacity of Married Persons Act of 2006, which removed the minority status of married women; the Land Act of 2010, providing for couples’ joint ownership of land; the Education Act of 2010, which mandates compulsory education for all; the Companies Act of 2011, allowing women to be directors and shareholders of companies without obtaining the consent of their husbands; and the Sexual Offences Act of 2003.

This dispatch reports on a special survey module included in the Afrobarometer Round 9 (2021/2022) questionnaire to explore Africans’ experiences and perceptions of gender equality in control over assets, hiring, land ownership, and political leadership. (For survey findings related to gender-based violence, see Malephane (2022).)

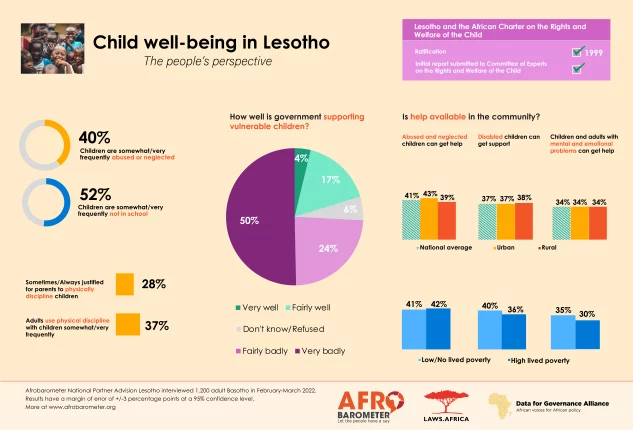

In Lesotho, strong majorities express support for gender equality in hiring, land ownership, and political leadership, including the right of daughters to succeed to the chieftaincy. But sizeable minorities also consider it likely that female candidates for elective office might suffer criticism, harassment, or family problems. Overall, a majority of Basotho disapprove of the government’s performance in promoting equal rights and opportunities for women and say greater efforts are needed.